Marching towards freedom

In 1983, 53 years after Mahatma Gandhi challenged the British Raj by undertaking the Dandi March and breaking the Salt Law, Thomas Weber, a professor of Politics and Peace Studies with La Trobe University in Melbourne, retraced the complete route of the march.

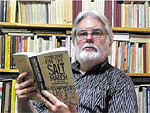

He is the only known person to have done this, and his 1997 book On the Salt March: The Historiography of Mahatma Gandhi’s March To Dandi relives both the original and the follower’s journey from a historical perspective. With the recent re-issue of the book by Rupa & Co, the ridiculously low amount of published, in-depth study in India on the historic march by Gandhi, on the scale of Weber’s book, has again come under focus, in turn underscoring the importance of this book.

In fact, Weber himself is quite amazed at this fact. As he says, “I am not sure why most of the books on the Salt March are little more than a collection of speeches. Perhaps library research is more comfortable than field work — but it is nowhere near as interesting or rewarding. I had no idea why no one had decided to research the event in the detail I had. After all, half a century had gone by.” Apart from the memoirs by some of the original marchers, nothing academic had been brought out on this one of the most important chapters of India’s Freedom Struggle, even though there have been regular events on various anniversaries organised by political parties.

Weber, who is hoping that with the re-issue the book would be picked up by general readers apart from academics, has been a researcher of topics related to Gandhi but his retracing of the Dandhi March route happened by chance, when an academic colleague asked him for information about the Salt March. “To my surprise, I realised how little was written on the key event itself. This intrigued me and I decided that I wanted to know more, and as someone who had been researching Gandhi in Australian libraries it was clearly time to go to India to find out about him in the place where his spirit was still alive and from those whose life he had personally touched,” Weber recalls.

During his own march, he met several original marchers, “a generation that is gone now.” Some of them remained his close friends till they passed away and from them he could learn about Gandhi’s personality. “Most of them told me that they were very close to Gandhi. I wondered how this could be possible — after all Gandhi knew an awful lot of people. Perhaps they wanted to impress me by bragging about their relationship with such an important person. But eventually I realised that it was part of the genius of Gandhi to make those he came into contact with feel special, that they had his undivided attention. And this was probably, dare I say it, because he did treat those around him in such a way that their feelings were not mistaken,” he says.

Weber, who has written several books related to Gandhi, is about to finish a book on his relationship with Western women, including the likes of Olive Schriener, Annie Besant, Millie Pollak, Maude Royden, Katherine Mayo, Margaret Sanger, Margaret Bourke-White, Mirabehn, Nilla Cram Cook, Marjorie Sykes and Saralabehn. Titled Going Native, it will be published issue by Roli Books and would look at why these women were interested in Gandhi, “and, indeed, why he was interested in them, and what impact they had on each other.”

Weber first became aware about Gandhi as a university student. “At that time Australia was involved on the US side in the Vietnam War and as the war was not overly popular, we had a system of military conscription to make up the necessary numbers of soldiers.

This made many of us, who were more or less apolitical until that time, start thinking about issues such as war and peace, imperialism, individual responsibility and civil disobedience. Gandhi was a pointer in my new political thinking,” he says.

For Weber, Gandhi’s relevance is greater than ever now, “though it sounds like a cliché.

In some senses Gandhi is disappearing, being turned into an icon. But Gandhi provided an important critique of a way of living that is leading the planet into dual economic and environmental disasters. In many aspects he was far ahead of his time. We do not heed much of what he said at our own peril,” he says.

His experience about Gandhian values in present-day India is mixed. “Many of the old Gandhians I had come to know have disappeared. Hardly anyone spins at the charkha anymore, the institutions of old Gandhians become museums, and institutions set up by Gandhi seem ever more anachronistic. Interestingly, as there is less and less contact with the Mahatma through those who knew him, there is a corresponding increase in the number of course on Gandhi and journals dedicated to his philosophy. Many youngsters have little idea of what Gandhi stood for. They know him as the father of the nation, but little more. But there are also a great many inspirational youngsters in India who, even though they make no fetish of spinning or dietary restrictions and the like, and so may not be recognised as pucca Gandhians, are doing Gandhian work in the villages and peace work in the cities. Do we call them Gandhian? I think so,” says Weber.