No relief in sight for industries stung by supply chain woes

Rahul Kamath has been footing astronomical bills to ship his company’s cashew nuts abroad ever since the Covid-19 pandemic began.

The Karnataka-based proprietor of Bola Surendra Kamath and Sons said ocean freight accounts for nearly 10 per cent of the cost of the cashew these days due to the global cargo container shortage, versus 2 per cent in pre-pandemic times.

“We have to bear the cost, because if the retailer in Dubai increases costs, the demand will come down,” laments Kamath, whose firm has been in the business since 1958.

The cost of shipping a single container from Mangaluru to Rotterdam stands at $6,000, more than ten times what it was, he points out, while the cost of shipping to Dubai stands at $3000, where it was anywhere between $300 and $500 before.

“The contracts are often drawn up in advance, and this is a global crisis, so we cannot do anything about it,” says Kamath, who has been frustrated with the lack of sufficient containers at the Mangaluru port.

“There are just three to four shipping lines operating here, and the prices have gradually been rising since the start of the pandemic.”

Many Indian exporters have been in the same boat as Kamath since the deadliest viral outbreak in a century upended the global supply chain.

So, what happened?

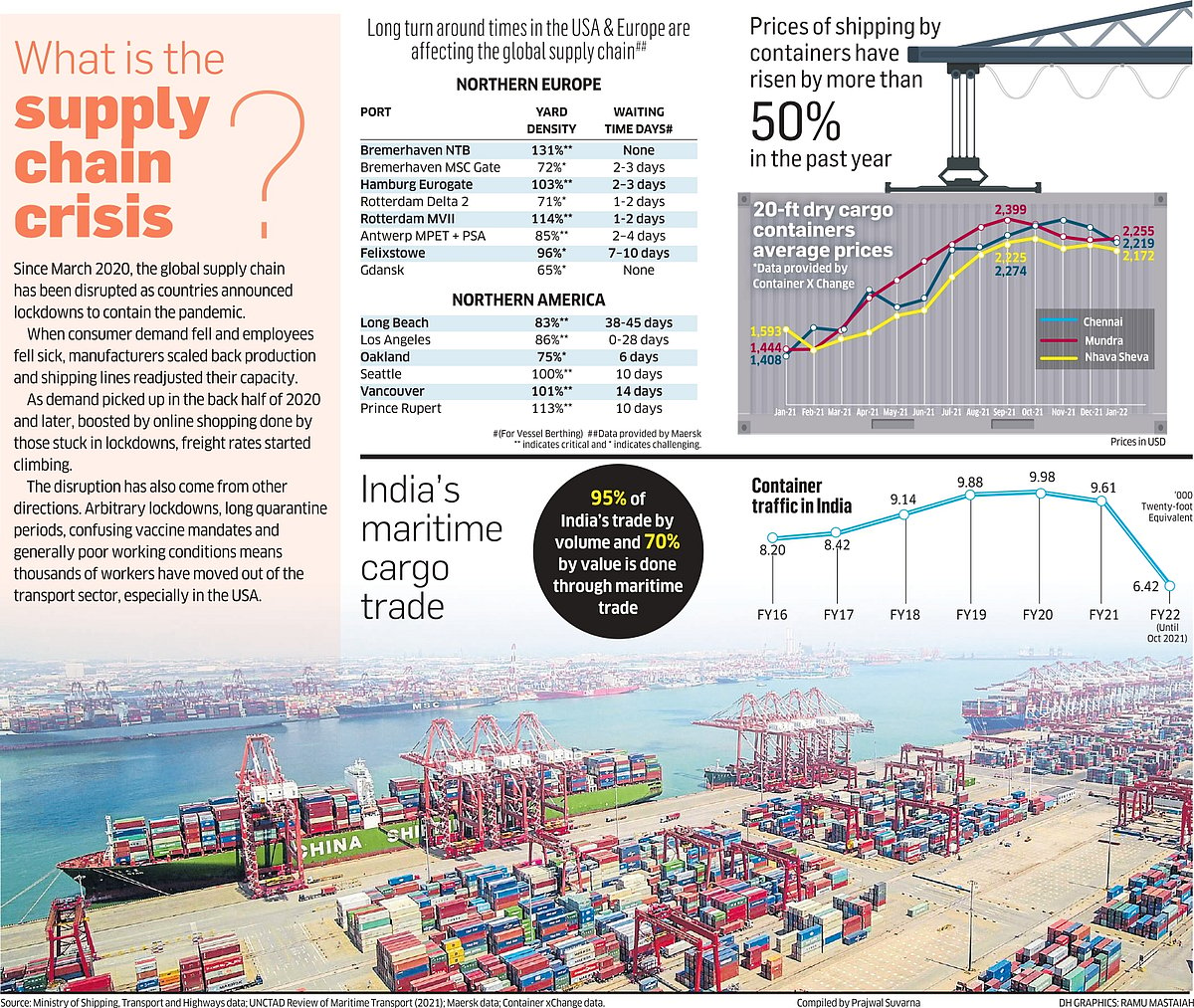

When the pandemic gripped the world in early 2020, countries announced lockdowns to contain its impact, temporarily leading to a decline in consumer demand. That made shipping lines assume they would need fewer vessels in operation and readjust their capacity, routes and operations.

Fast forward to August 2020, and freight rates started climbing as demand for shipping services rose after people started buying more goods online when they found it unsafe to travel, dine out and go to the movies.

To make things worse, pandemic-induced lockdowns at key ports ranging from Shanghai to Los Angeles meant a dearth of people to load and unload goods from the vessels, increasing the time taken to send empty containers back.

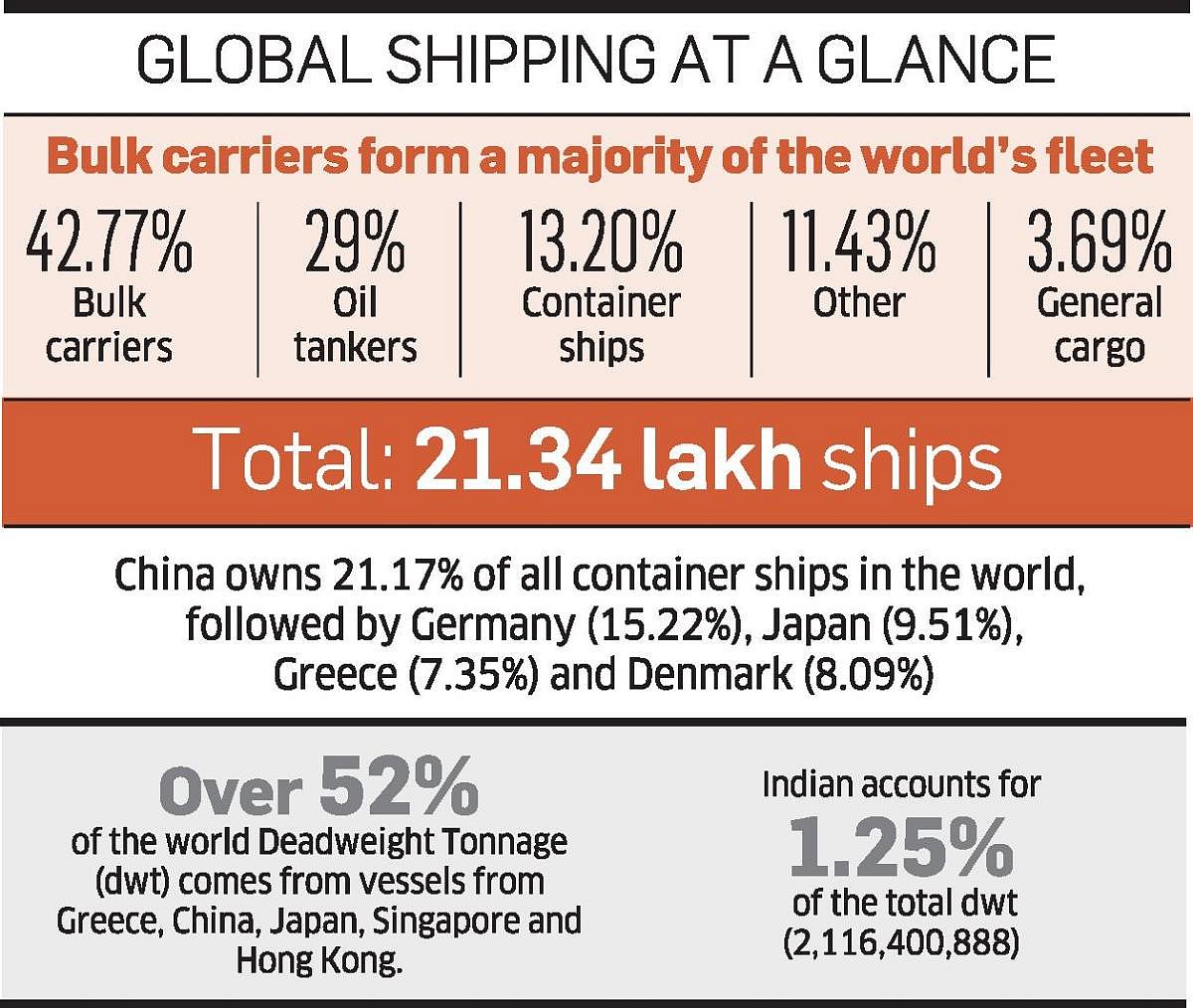

While demand surged, the shortage of cargo containers and vessels to move them between countries worsened. Cargo containers are typically owned by a shipping line or by a container leasing company.

To manage the crisis, shipping companies decided to focus on the routes connecting consumption-driven developed countries such as the United States and Europe to China, often called “the factory floor of the world”.

This meant that exporters in countries such as India got fewer or smaller vessels to ship their goods, faced extreme delays and had to cough up extraordinary amounts of money whenever they had a chance to put their stuff on a ship.

Small and medium-sized businesses in India, with very little bargaining power, had no choice but to pay more or get stuck with their ware.

India’s shipping ministry has not responded to an email seeking comment on how it plans to address the ongoing container crisis.

And going by what logistics experts are predicting, things are not going to improve any time soon.

“It will probably be in 2023 that we will see a market akin to what we have pre-pandemic,” says Peter Sand, chief analyst at Xeneta, a leading ocean freight rate benchmarking and market analytics platform. Brands ranging from Tata to Volvo rely on Xeneta data to minimise supply chain disruptions.

“Many things must unwind and correct, before ‘business as usual’ can continue. This goes for India as well as the rest of the world. The first signs of an easing will show on the Transpacific Eastbound trade lane, later it will also diminish the ripple effect on many other trades,” Sand says, confirming that Indian importers have seen higher freight rates following a hike on international trade lanes.

“Indian exporters have probably also been hit by a lack of available equipment for exports as carriers in all places have preferred a quicker turnaround of containers, to make them available in the Far East more rapidly,” he adds.

Indian exporters might find it hard to put their ware on a ship abroad even if they are willing to pay more, since data from Sea-Intelligence, a supply chain research firm, shows 11.5 per cent of the global capacity has been taken out of the market due to vessel delays in November 2021.

“There is a shortage of capacity everywhere, for as long as massive delays prevail,” he says.

Global container shipping schedule reliability was as low as 33 per cent in November, according to Sea-Intelligence, and for trades out of India, it was even worse.

For instance, reliability for a trade lane like the Indian West Coast to North Europe was 49 per cent in November, down from 56 per cent in September. “That equals an average late arrival at 5.3 days. So, moving in the wrong direction,” Sand explains.

Meanwhile, it’s getting better on another trade lane, but from an awfully low point: Indian West Coast to Far East.

So what options do exporters have?

“Making your supply chain more resilient either requires higher inventories, more goods moving earlier or setting up a production facility nearer the export market to avoid the current hurdles. Options are available anywhere in between the two extremes,” says Sand, who urges exporters to plan better for the future.

“If you can sign a long-term contract, and perform, it’s probably better than being at the mercy of the spot market,” he says. Reports by the International Air Transport Association shows that global air cargo traffic had started on an upward trend starting from the second half of 2020. By July last year, it had surpassed the precrisis peak of August 2018.

Even here, increased demand has led to a rise in rates. The lack of international flights has also limited the amount of belly cargo capacity (air freight transported on scheduled passenger flights). But there was a 12 per cent rise in the size of the global air freighter fleet between January 2021 to July 2021, compared to the same period in 2019.

The Omicron problem

Experts had originally expected things to get better in 2022.

“Omicron made a dramatic entry just when the world started preparing for the comeback of the supply chain. Now partial lockdowns in China, which is the epicenter of container manufacturing and supply in general, will have a ripple effect on the supply chain,” says logistics technology firm Container xChange.

Sure enough, ships looking to avoid Covid-induced delays in China are making a beeline for Shanghai, causing growing congestion at the world’s biggest container port, Bloomberg reported on January 13.

Shipping firms are making the switch to avoid delays at nearby Ningbo, which suspended some trucking services near that port after an outbreak of Covid-19, the news agency reported, citing freight forwarders and experts. Ships are also re-routing to Xiamen in the south, Bloomberg shipping data showed.

This comes at a time when the US has been struggling to keep up with the many ships waiting to unload cargo filled in thousands of containers.

“What is being witnessed now is that the demand is continuing to remain higher than pre-pandemic times. This means the supply needs to keep up,” Container xChange says. “This will eventually mean that the supply-demand gap will only widen, thereby bringing bad news for the container prices.”

A shipping container that cost around $1500 for a 20-feet dry container and $2000 for a 40-feet dry container pre-pandemic, now costs an average of $2250 for a 20-feet dry container in India’s largest container port Nhava Sheva and $5200 for a 40-feet dry container in Chennai, according to Container xChange data from December 2021.

“Owing to the rising difficulties for Indian exporters, the year 2022 is set to witness two things — inflationary costs of goods and an increase in the net trade deficit. What remains to be seen is how the industry prepares for it,” Container xChange says.

Delay in imports

At a time when there is container demand in China, as is the case now, it is observed generally that containers are redirected to China from India. “This means container crunch remains in the country for a longer period and is more acute. If the vessels are directed to China and other countries of priority, imports in India will be delayed. This could potentially result in low availability of goods for the end consumer,” the container logistics platform says.

In an advisory dated January 11, shipping giant AP Moller-Maersk told its customers that “2022 has not started off as we had hoped”.

“The pandemic is still going strong and unfortunately, we are seeing new outbreaks impacting our ability to move your cargo. General sickness remains high as key ports in key regions are seeing new Covid-19 peaks,” Maersk acknowledged.

A Maersk spokesman told DH it was hard to predict until when the global logistics crunch would persist.

“We do not want to guess when and how the situation will change. The current Omicron outbreak is a classic example of the events turning all the time. Without it, we may have been moving faster towards normalisation. It is tough to predict as the situation in the different ports changes again and again; some for the better, some for the worse. Sometimes we even see the problem move from one port to another as ships are being redirected to a port with a short waiting time,” said Bhavik Mota, Director, Regional Ocean Management, Maersk West & Central Asia.

(With inputs from Prajwal Suvarna in Mangaluru)