Article 15 India’s first ‘Constitutional’ film?

Article 15 is perhaps the first film that is focusing on an article in the Constitution, but this does not mean films haven‘t referred to the Constitution over the years.

Political and socio-cultural films often uphold or go against the values of our Constitution.

For instance, look at Shekhar Kapur’s Bandit Queen (1994), which remains a critical gem to this day.

Despite its success, there was one portion that made it very problematic for India: Arundhati Roy slammed it in her essay ‘The great Indian rape trick’.

She argued the film showed the rape of a living woman on screen without her permission, when the Constitution upholds a woman’s right to protect her modesty.

On the other hand, some films that have run into controversies, or faced censor ire, have upheld some of the Constitution’s most cherished values.

Mrinal Sen’s Neel Akasher Neechey (1959) told the story of the friendship between a Chinese labourer and a politically active woman during the Indian freedom struggle in the 1930s.

The ban on Sen’s film (although it overtly stresses the importance of the freedom struggle) was based on its communist take, stressing the class divide in India during the all-unifying strife.

Today, the ban on it seems silly. Another example of a film that upholds constitutional values but was blocked for eight months was M S Sathyu’s Garam Hawa (1973).

Its fault was to depict the concerns of a Muslim family right after Partition. They choose India and refuse to flee to Pakistan. As taking care of our minorities is written into the Constitution, which also asks us to put our country first, this film must have, in fact, checked all the boxes, but alas!

Films that critique (not even attack) Gandhi are often brought down by the censors for their supposedly anti-national content, which is odd since nowhere in the Constitution is Gandhi referred to as the ‘Father of the Nation,’ which is actually a phrase handed down in our oral history.

The Malayalam film Papilio Buddha (2013) had shown a speech by Ambedkar where he criticises Gandhi for denying Dalits electoral constituencies; some Dalit characters in the film burn Gandhi’s effigy. The censors passed the film only after the ‘offensive’ speech was muted and some scenes were blurred.

One instance of a film that in fact went against a Constitutional value is Deepa Mehta’s Fire, which spoke about a lesbian relationship when Article 377 still criminalised homosexuality.

Although the censors gave a thumbs-up to the movie, hooligans attacked theatres, indulging in acts criminalised by the Constitution.

For those who think Fire should have been banned for disrespecting a Constitutional provision, how can violence not also be condemned?

What Article 15 seems to want to do is take the bull by its horns and speak about discrimination.

While we should welcome films that uphold constitutional values, we should also make sure they are protected from vandals and mischievous litigants.

Releasing today

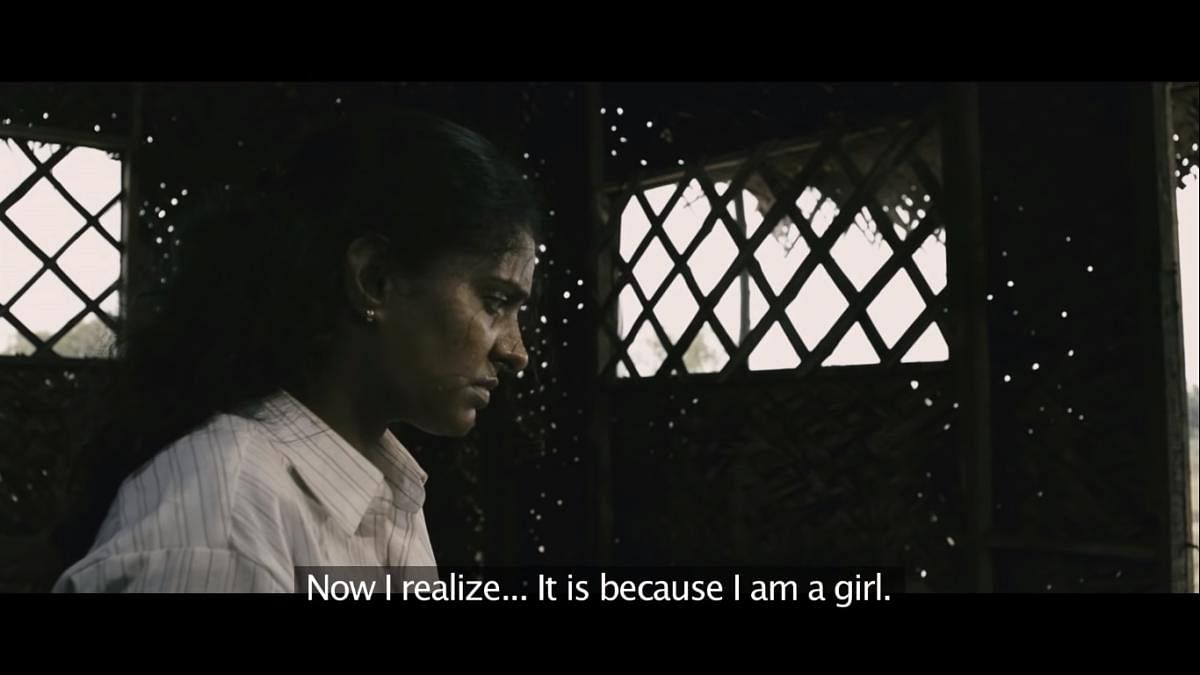

Article 15 refers to an article in the Constitution that prohibits discrimination on the grounds of religion, race, caste, sex and place of origin. The Hindi film stars Ayushmann Khurrana in the lead, and is a take on the 2014 UP case in which two Dalit teenage girls were raped. It also refers to the flogging of a Dalit in Himachal Pradesh.