Without digital infra, govt apps are roadblocks, not solutions

In Assam’s Dibrugarh, Mainu, an Anganwadi worker, was tasked with filling in data for the Ministry of Women and Child Development’s POSHAN Tracker app. The application tracks several development parameters of the Integrated Child Development Services. While the innovation seemed good on paper, in practice, she faced several roadblocks.

To start with, the smartphone that the government gave her stopped functioning after six months. “They gave us faulty devices, I spent money fixing it, and then it stopped working again. I am now using a personal phone,” she says. She is also forced to spend more money on internet packs due to the absence of a wireless network in her office. Mainu draws a salary of Rs 8,500 per month.

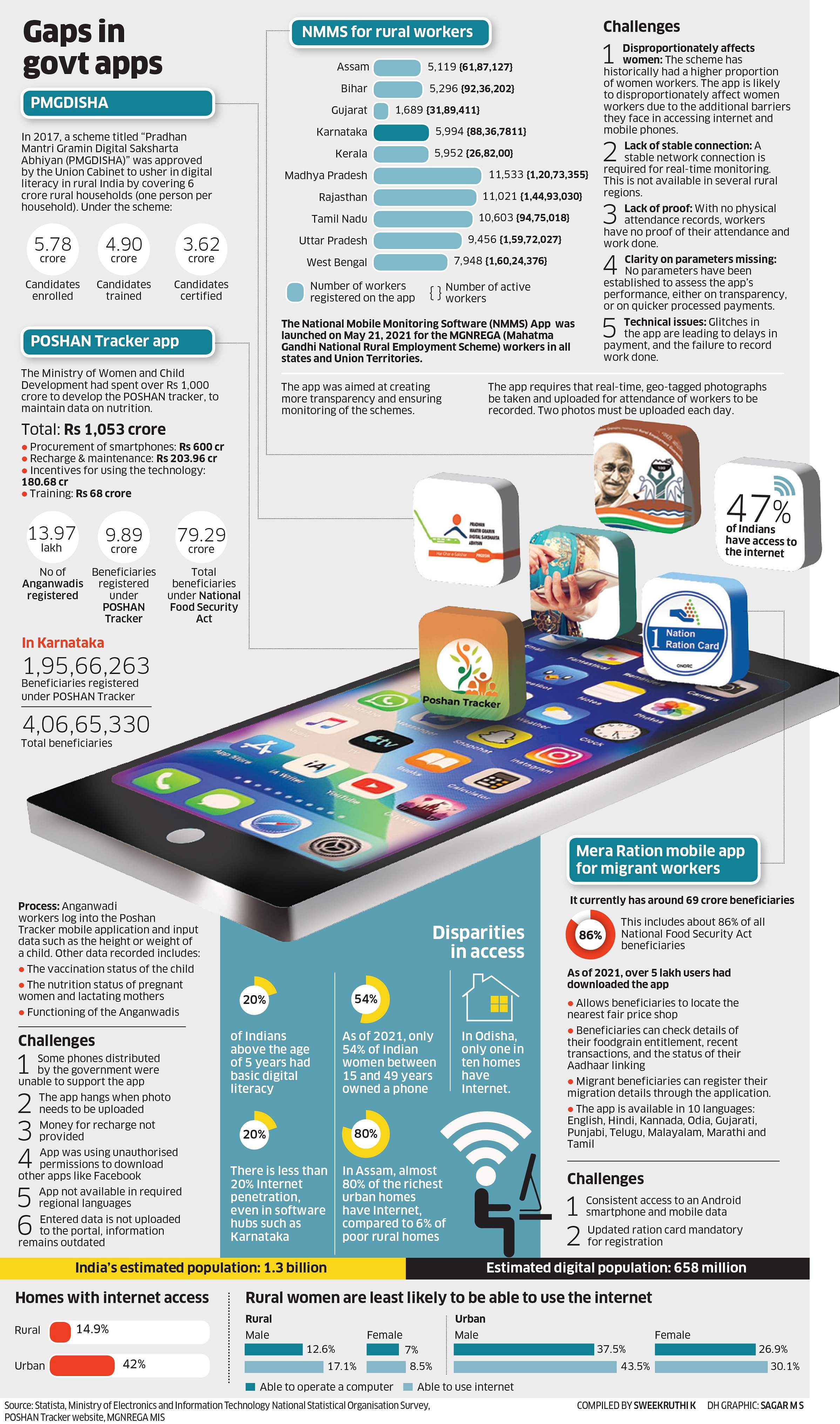

Through the ‘Digital India’ campaign, the government has several such apps for the delivery of public services. In fact, it has over 40 for various utilities. But are these effective in a country where literacy is unequally distributed, and the penetration of internet and smartphones is limited?

There are two sides to this coin — while digitisation brings with it the potential to improve documentation, and thereby, implementation, it could also be worsening the reach of schemes in cases where access to technology is not available or affordable. While the online system allows for the collection of real-time data, the disadvantages are becoming increasingly evident. Issues with internet availability and questions of privacy remain unresolved.

For instance, one app that remains bogged down by problems is the National Mobile Monitoring Software (NMMS) app used to record attendance for the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA). Many workers do not receive their daily wages due to faulty internet access during the time windows allotted for digital attendance.

On the POSHAN Tracker app, noting down key parameters including height, weight and the circumference of a child’s arms is simply not possible for many Anganwadi workers due to language barriers and lack of a smartphone. Workers are also finding the process of entering data tedious and time-consuming.

The app enables the live tracking of nutritional parameters. The scheme also provides benefits to pregnant and lactating mothers and gathers data points relating to the women, including their nutritional status and needs. To date, more than 11 lakh smartphones have been procured to enable Anganwadi workers to upload data on the tracker.

However, Anganwadi workers across the country said it is easier said than done. Both state and central governments have allocated funds for the mobile devices that they have distributed, and Anganwadi workers often have to pay out of pocket for devices that malfunction. Many lack the knowledge of how to operate a smartphone.

In 2021, after several such complaints, Anganwadi workers in Maharashtra started returning their phones back to the government, prompting an audit.

Pushpa, an Anganwadi worker from Haryana’s Jind, says that even with a functional internet connection, she and her colleagues spend hours updating the data.

“On average, we spend one to two hours per day just to do the uploading. The government argues that our work is voluntary and disagrees with us when we ask for a hike, but we spend so much of our day just doing this, time which can better be put to taking care of the children in the Anganwadi,” Pushpa says.

In addition to that, the app is not available in regional languages, says Raj Shekhar of the Right To Food Campaign, who has taken up these issues with the government. Glitches on the tracker have cropped up since it was started in 2016, and yet, there is no mechanism for redressal.

Beneficiaries, too, have complained time and again. “Another disturbing development is the use of Aadhaar as an entitlement criterion. The government has denied it, but several states have received notifications to make Aadhar a requirement on the app. It goes against the Supreme Court verdict. Also, in the case of children under a certain age, the iris datasets cannot be used, but in many states they are used for the registration of Aadhaar cards due to compulsion from authorities,” said Shekhar.

As of 2022, as many as 9.89 crore beneficiaries were part of the app, and the ministry had made its use compulsory in 2021.

NMMS app

Equally rife with glitches, the NMMS app was first launched by the Ministry of Rural Development in May 2021 to ensure that workers engaged under the MGNREGA could mark their attendance. The app was an initiative of the NITI Aayog. It requires that workers’ attendance is logged by uploading geo-tagged photographs twice every day, within a specific time window.

The initiative was initially launched as voluntary but is now increasingly used by governments across several states. The consent of these workers, the Internet Freedom Foundation has said, has not been taken into account. What is worse is that since wages are linked to attendance, many of the workers have lost pay.

After the app is downloaded, a “mate” who is responsible for the attendance of around 20-40 workers, registers, after which a local authority gives them the credentials. The app requires high-speed internet and workers can begin to log their attendance online from 6 every morning. The attendance of the workers comes in a muster roll of 10 workers, and the mate has to tick each name and upload the log, after which they need to take a live photo of the workers and upload.

Virupamma, a mate in a village in Raichur, says that she and her friends have lost out on wages several times after the app was launched. “Every morning, we pray that we will get mobile service to register our attendance that day. In my group, for instance, a worker had worked for seven days and I marked the same on the app. He was only paid for five days,” she says.

“There have been times where workers have put in labour for 14 days, but have been paid only for five,” she adds.

Network issues are the cause behind most of the problems, and to resolve that, Virupamma says, they are forced to approach the Panchayat Development Officer, who may hear the case or reject it: “We have been forced to go to even the taluk panchayat officials.” Many workers abandon redressal mechanisms as they are long-winding and require the intervention of many officers.

Server capacity

Shilpa Nag, Commissioner of Rural Development and Panchayat Raj (RDPR) Department, Karnataka, acknowledges technical glitches and connectivity problems after six months of use in the state. “There are technicians and gram kayak mitras who are working on the ground to resolve problems,” she says. Right now, most issues stand resolved. “Some issues have been reported with the 2nd attendance registration. We are continuously working with the National Informatics Centre, Delhi to get these issues resolved,” Nag said. Furthermore, the District Programme Coordinator, who is the Chief Executive Officer of the district panchayat, has the authority to correct any errors in attendance recording, she added.

An official in the RDPR department explained that recent glitches in the app were occurring due to the inclusion of attendance for worksites with less than 20 labourers. “Karnataka is the highest user of the application. The Centre must think of increasing the server capacity,” the official said.

The Opposition has shed light on these hiccups as well. Congress’ communications chief and former rural development minister, Jairam Ramesh, has criticised the government over the issues. He explained that earlier, physical muster rolls required each worker to sign. These were available to all and subject to social audit. The new app has introduced new problems like denial of work or payment when the server is down. Workers wait for hours for a group photo, he added.

Maalamma, who is also a mate from Kalmala village in Raichur, said that when she tried to register 60 workers, only 35 were accepted; the rest were rejected due to Aadhar linkage issues.

“When we complain, we are told that there are server issues. My family is into agricultural labour. MGNREGA work is crucial for us to make ends meet in our family of seven,” Maalamma says.

Access, a challenge

An additional barrier is the requirement for all mates to have smartphones to use the app. “People without expensive smartphones — especially women, Dalits and Adivasis — cannot be mates,” Ramesh said in a recent statement.

In most families, women have restricted access to a mobile phone. This means that more and more women are dropping off from the workforce. Shekhar says that ironically, all the issues that Anganwadi workers have been facing in the case of Poshan Tracker are now cropping up with the NMMS.

Mukesh Nirvasit from the Mazdoor Kisan Shakti Sangathan says that in the case of complaints, no additional help has been provided by the authorities. “Earlier, the gram panchayat was the last authority, and then it moved to the blocks. And now slowly, the system will be run from Delhi,” he notes.

When a delegation of worker's unions met the secretary of the rural development ministry, they were told that the app was helping weed out corruption, says Nirvasit. “There are 50 crore beneficiaries of the MGNREGA, and workers have to upload pics twice a day, but who is watching? There are over one crore pictures a day, some people upload pictures of a ball, some upload pictures of a tree. This is just a way to harass workers,” Nirvasit adds.

(with inputs from Varsha Gowda in Bengaluru)