A solar eclipse of a smaller scale can occur when, instead of the moon, Mercury or Venus moves between Earth and the sun. These are termed transits and are not as frequent as the lunar or solar eclipses. The transit of Venus can be as rare as once in 105 or 121 years, though it occurs as a pair that is spaced 8 years apart. Thus, we had two quite recently in 2004 and 2012. Transits of Mercury are more frequent. Owing to the elliptical orbit, the frequency ranges from 3 years to 13 years. In India, we had the opportunity to see it in 2003. We were positioned very favourably and had the entire sequence visible to us. The one in 2006 was not visible in India. Now, we look forward to the next one on May 9 when the event is partly visible to us towards the evening.

Assessing the transit

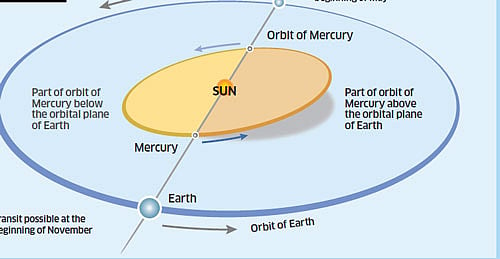

The basic requirement for the event to happen is the alignment, which can be technically specified as the planet (Mercury or Venus) being on the node at the time of conjunction. Conjunction is a more general term. It happens almost once in 2 years for Venus and 3 times a year for Mercury when they move between Earth and the sun. However, owing the small (about 7 degrees) inclination of (Mercury’s) orbit to that of Earth, the alignment cannot occur at every passage. It implies that the planet will be seen slightly to the north or south of the sun. It can be colloquially stated as ‘above’ or ‘below’ the sun so that its visibility is limited to the space observatories. For example, the recent conjunction that occurred on August 13, 2014 was recorded by Solar & Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO), the orbiting observatory.

If we consider the orbital planes of Earth and Mercury, we see that Mercury necessarily passes through the plane of ecliptic (that of the orbit of Earth) at 2 points which are defined as nodes. Just as in the case of moon they are defined as ascending and descending nodes. The movement from south of ecliptic to north occurs at the ascending node and it is vice-versa for the descending node. The nodes correspond to the position of Earth on May 8-9 and November 14-15. Thus, if the conjunction occurs on these dates there is a definite possibility of the transit.

As can be guessed, the May transits correspond to one node and the November ones to the other. This can be verified by the observations made on the 2003 event when Mercury moved across the sun not parallel to the solar equator but from north to south. That was the descending node. The November events show the passage from south to north and correspond to the ascending node. The very first transit was observed by Pierrie Gassendi, on November 7, 1631, and it had been predicted by Johannes Kepler earlier. Quite interestingly, the following event was observed by Jeremy Shakerly in Surat, on November 3, 1651. It should be remembered here that such an observation requires a telescope projection system for safe viewing.

For careful observations

Although expertise on theoretical calculations of this nature existed among Indian astronomers, an actual record of such an event is not yet available. A couple of stone inscriptions mention the conjunction aspect; it does not necessarily imply an

observation. On the other hand, if the transit occurred at sunrise or sunset, there is a possibility of having observed the event.

The forthcoming event starts at about 4:30 pm and is visible all over India. It continues beyond the sunset here and hence can be safely observed at sunset. It is best visible for countries in Africa and Europe at noon; the advantage we had in 2003. However, as the size of Mercury is small, recognising it as a black dot requires extra effort. A magnification tool is definitely needed unlike in the case of Venus which was strikingly noticeable as a fairly large spot. The first contact occurs at 4:32 pm; however, the entrance of the dot may go unnoticed since the contrast at the edge is not sufficient enough as can be seen in the photograph of the event in 2003. Within 2 minutes, the entire disc of Mercury appears as a dot on the solar disc and becomes identifiable. As it moves towards the centre of the disc the visibility improves. The central point occurs at 8:27 pm and the sun would have set long before that for us in India. Therefore the best opportunity is around 5:30 pm when the effect of atmospheric absorption is still not strong enough. Photographing the sunset would be the safest.

The observation involves looking at the sun and hence all the precautions are essential. All the instructions for observing the solar eclipse are applicable here too. The eclipse goggles may not help. To view the eclipse better, one can seal the objectives of the binoculars by adding mylar sheets as a filter. The magnification provided by binocular should suffice to show the event. Projections with small telescopes will be ideal.

The transit offers a very good opportunity for many to learn as it offers one to do simple experiments like estimating the velocity of the planet since the disk of the sun provides an excellent screen for comparison. The event can also be used for getting the angular size of Mercury and hence the distance. This opportunity can motivate students to take a different approach towards celestial events. This will lead them to be more inquisitive to explore the hard work of our ancestors.

(The author is director, Jawaharlal Nehru Planetarium, Bengaluru)