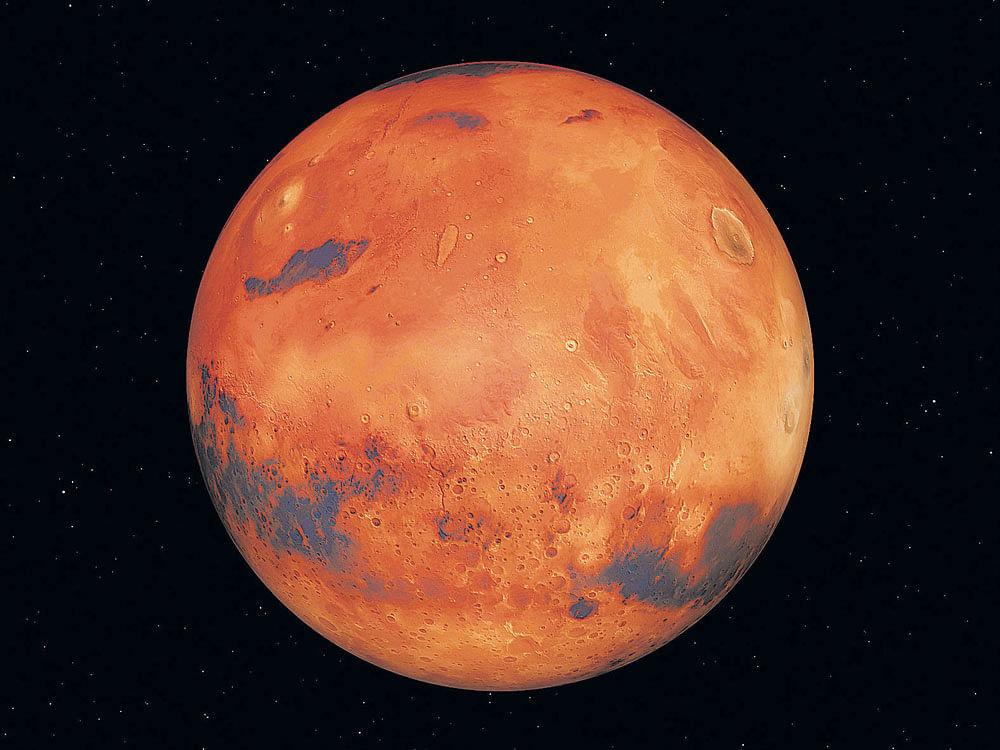

Winter on Mars - which causes carbon dioxide to freeze - alters the appearance of sand dunes, according to a study that explains how land features are formed on the red planet in the absence of large amounts of liquid water.

Researchers conducted lab-based experiments on carbon dioxide (CO2) sublimation - the process by which a substance changes from a solid to a gas without an intermediate liquid phase.

The findings suggest the same process is responsible for altering the appearance of sand dunes on Mars.

"We have all heard the exciting news snippets about the evidence for water on Mars," said Lauren Mc Keown, from Trinity College Dublin in the UK.

"However, the current Martian climate does not frequently support water in its liquid state - so it is important that we understand the role of other volatiles that are likely modifying Mars today," said Mc Keown.

"Mars' atmosphere is composed of over 95 per cent CO2, yet we know little about how it interacts with the surface of the planet," she said.

"Mars has seasons, just like Earth, which means that in winter, a lot of the CO2 in the atmosphere changes state from a gas to a solid and is deposited onto the surface in that form," she added.

"The process is then reversed in the spring, as the ice sublimates, and this seasonal interplay may be a really important geomorphic process," she said.

Several years ago, researchers discovered unique markings on the surface of Martian sand dunes called Sand Furrows.

These elongated shallow, networked features that formed and disappeared seasonally on Martian dunes.

"What was unusual about them was that they appeared to trend both up and down the dune slopes, which ruled out liquid water as the cause," said Mary Bourke, of Durham University in the UK.

The researchers designed and built a low humidity chamber and placed CO2 blocks on the granular surface. The experiments revealed that sublimating CO2 can form a range of furrow morphologies that are similar to those observed on Mars.

Linear gullies are another example of active Martian features not found on Earth. They are long, sometimes sinuous, narrow carvings thought to form by CO2 ice blocks which fall from dune brinks and 'glide' downslope.

"The difference in temperature between the sandy surface and the CO2 block will generate a vapour layer beneath the block, allowing it to levitate and maneuver downslope, in a similar manner to how pucks glide on an ice-hockey table, carving a channel in its wake," said Mc Keown.

"At the terminus, the block will sublimate and erode a pit. It will then disappear without a trace other than the roughly circular depression beneath it," she said.

By sliding dry ice blocks onto the sand bed in the low humidity chamber, the group showed that stationary blocks could erode negative topography in the form of pits and deposit lateral levees.

In some cases, blocks sublimated so rapidly that they burrowed beneath the subsurface and were swallowed up by the sand in under 60 seconds.