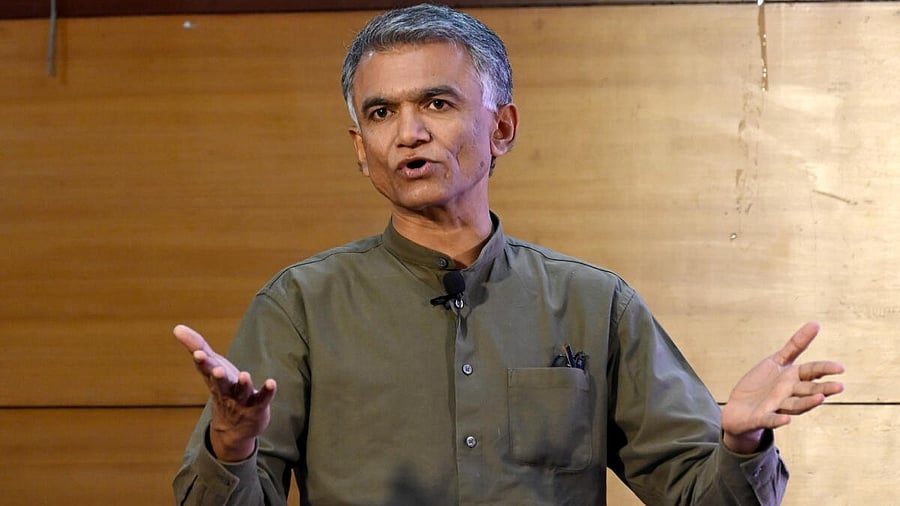

Krishna Byre Gowda.

Credit: DH Photo

Karnataka is for GST rate rationalisation. All states, regardless of the party governing them, are supportive. But at the same time, we are seeking protection for the likely loss of revenues for the states due to rate rationalisation.

The states are constitutionally entrusted with the majority of developmental responsibilities. However, the majority of revenue sources are entrusted to the Central government. In addition to this structural imbalance, any further shock to the states' revenues will severely impact public welfare, fiscal federalism, and their autonomous functioning.

We can illustrate the situation with the example of Karnataka. Before the introduction of GST, Karnataka was experiencing a robust growth of around 15 per cent in its VAT revenues. The VAT revenues from items later subsumed into GST amounted to 3.6 per cent of the state’s GSDP. If the state’s GST revenues had grown at 13 per cent, continuing the growth trend before GST, it should have had a GST revenue of Rs 1,07,846 crore in 2024-25. However, it only got Rs 86,475 crore – a loss of Rs 21,371 crore in one year.

During the same period, Karnataka’s share of devolution and grants (both coming from the Central government) has been cut from 31.4 per cent to 22.7 per cent of its total revenue receipts. On this reduction of devolution and grants, the state is losing close to Rs 40,000 crore per year.

All these have occurred during the years when Karnataka’s economic growth has been higher than the national growth, and its GST growth has been among the top three in the country. In fact, the state’s contribution to the country’s GST collection has increased from 8.9 per cent to 9.5 per cent. This means we have grown much more than others, generating more revenue. This is also the period when Karnataka reached the number one position in per capita income. So, even as Karnataka continues to perform at the top, whatever revenue remains with us is shrinking. Despite our best performance, this loss of revenue is due to factors that are beyond our control.

At the time of the introduction of the GST, all states and the Centre agreed that the rate of GST should be the same as the combined taxes before GST (array of VAT, Central Excise, etc.) The weighted average of pre-GST taxes (revenue-neutral rate, in other words) was estimated to be around 14 per cent. Net rate of GST has already been brought down from 14.4 per cent at the time of GST introduction to about 11 per cent by several rounds of rate cuts, mostly led by the Centre. In all this, the theory of revenue buoyancy has been pushed. The reality is that starting from the introduction stage and through every rate cut, the revenues have declined. This source contributed to an all-India revenue of 6.1 per cent of GDP before the GST was rolled out. Today, it is down to 5.9 per cent (likely to further come down to 5.5 per cent or less with the current proposal for rate cuts).

Instead of buoyancy, there has been a net decline in revenues. On top of that, several studies have established that the benefit of rate cuts is not being fully passed on to consumers and is partly pocketed by businesses, leading to windfall profits.

In the current discussion, the health and life insurance sectors have categorically declined to make any commitment to pass on the full benefit of the rate cut to people and have asserted the right of the businesses to make a profit (even in this context).

With the proposed rate cuts, the net effective GST rate will come down to around 10 per cent. We need to make a realistic assessment of buoyancy and the extent to which it can compensate for revenue loss.

The Centre has neither shared with us an estimation of revenue loss nor has it provided us time to make a realistic estimate. We are rushed to make a major decision without full knowledge and the time to evaluate. Financial institutions and experts have estimated revenue loss from current proposals to be in the range of Rs 85,000 crore to more than Rs 2,00,000 crore. The revenue losses to the states are estimated to be about 15-20 per cent of their current GST revenues. Some may argue that the losses will also affect the central government. But the Centre has a far greater fiscal capacity and broader revenue base with substantial inflows from direct taxes, customs, excise, cesses and dividends from key PSUs or institutions. The Centre’s GST revenues account for 28 per cent of its Own Tax Revenue. But the states’ dependence on GST is far higher, contributing 50 per cent of their Own Tax Revenue. Hence, this will impact the states far more and cause a permanent shock to the states’ fiscal capacity and autonomy.

After the end of GST compensation in 2022, the states suffered a fiscal cliff when their GST revenues dropped by 20-25 per cent. The current proposal will deliver another fiscal cliff, further destabilising the already precarious state finances. Fiscal federalism will take a blow. Resource limitations ultimately limit the state's autonomy and its ability to deliver development. This will cause long-term erosion of the ability of state governments and increase their dependence on the Central government.

A group of ministers (GoM), along with officers of the Central government, had deliberated on rate rationalisation and submitted a set of recommendations last year. Now, without any consultation with state governments, a completely new proposal has been placed for consideration. There has been no mention of the GoM’s recommendations in this proposal. Contents are extensively leaked even before being made available to states. This is hardly a model for cooperative federalism.

Cooperative federalism requires states to be consulted not just in form but in spirit. Estimates of loss are not shared; sufficient time is not allowed; nothing happens for nine months; and then, everything should be decided and done in a month.

Yet, we are ready to work and cooperate with the Central government constructively for the benefit of the people. All we seek is that protection be offered to the states against the significant revenue losses. If the Central government does, indeed, believe in the revenue buoyancy, it should easily and readily agree to revenue protection. Buoyancy will ensure there is no major revenue loss. Hence, the question of compensation will not even arise. Compensation, if there is to be, need not even come out of the central exchequer. The current cess in GST can be replaced by a levy which, in turn, can be used to compensate for losses by the states. This is a win-win proposition without even burdening the Central government. So, all the like-minded states have placed a proposal.

We are hopeful that the Central government will understand, work with the states positively and agree to our proposal, so that we can all move forward in the spirit of GST and cooperative federalism.

(The writer is the minister of revenue in the Karnataka government.)