Minds on the margin are not marginal minds, remarked Prof Anil K Gupta in 2009 at the TED-India conference while addressing a gathering of people interested in technology and design. Being executive vice-chairman of the National Innovation Foundation (NIF) in Ahmedabad, Prof Gupta regularly sifts through a database of nearly 1.7 lakh innovative ideas predominantly filed by economically challenged grassroots innovators.

A significant number of ideas Gupta painstakingly browses through deal with sustainable and cost-effective solutions to problems faced by the so-called ‘aam-admi’ in his day-to-day work and existence. To utilize these “inspired” innovations towards achieving the ends of inclusive growth and ecological sustainability, the government of India has declared 2010-2020 as the Decade of Innovation and set up National Innovation Council (NInC).

The NInC aims to facilitate an Indian model of innovation that is inclusive and caters to the needs of people at the bottom of the social pyramid. For complete inclusion, it needs to reach out to grassroots innovators on a sector-to-sector and state-to-state basis, with the added responsibility of protecting their intellectual property rights.

However, the changing priorities of grassroots innovators were clearly evident at a recently concluded National Science Expo in Thiruvananthapuram.

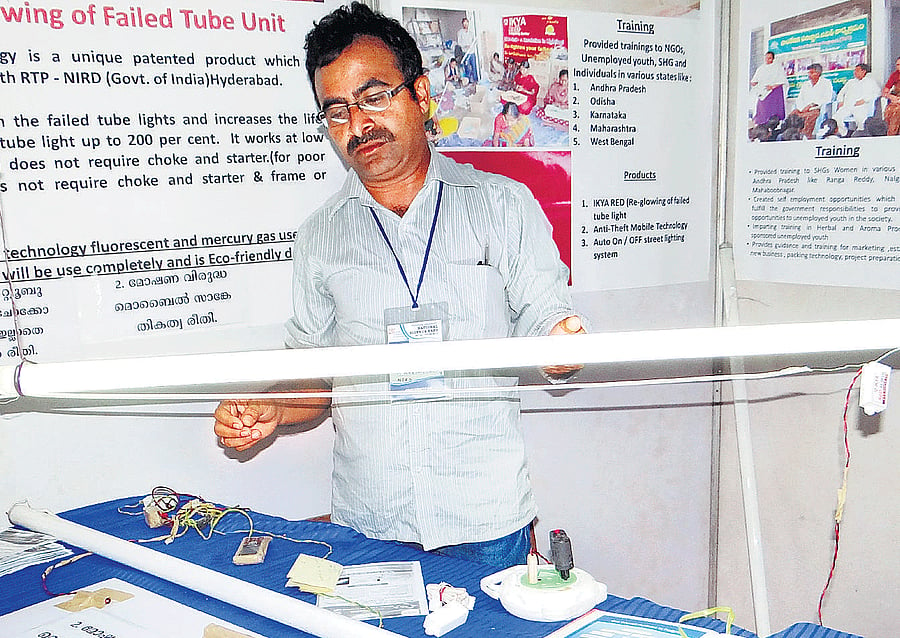

Though awareness and innovation in the energy sector has been a recurring theme of the expo, apart from an idea about relighting malfunctioning tubelights, none could really breach the economic barrier of making sustainable technology widely accessible and affordable. In contrast, the National Institute for Rural Development (NIRD), Hyderabad supports innovations such as soya-based food products and litchi-flavoured honey which has been a hit among distributors looking for novel products.

And, even with the timely recognition for their innovations and the novelty underpinning them, the people behind these developments paint a picture that reveals major loopholes which need to be filled urgently in this decade of innovation.

Mandaji Narasimhachary who hails from Navipet village of Andhra Pradesh is the inventor of the IKYA-ReD technology to relight malfunctioning tube-lights and CFL bulbs. He laments that while he has been handling a project worth more than Rs 200 crore, it has been a struggle to find an investor who can change the rules of the game.

Lack of support

Narasimhachary notes that despite getting repeated exposure for his technology in newspapers and television, he is hugely dependent on the government to understand and adopt his cheap, energy-saving and eco-friendly technology. This often leads him into signing exploitative memoranda of understanding with investors.

Prakash Vyas, an innovator in the food processing industry has evolved a few unique soya-based products, but alleges that banks still overlook the track records of entrepreneurs despite evidence to the contrary. He claims that they also misapply the funds given by the government to support rural entrepreneurs.

Against this backdrop, NInC has been looking to establish an India Inclusive Innovation Fund (IIIF) to drive and catalyse the creation of a rural innovation and enterprise ecosystem through venture capital targeted at developing innovative solutions for the bottom of the pyramid. With an eventual target corpus of Rs 5000 crore, the fund is looking to act as a provider of opportunities. This will include risk funding, a primary hurdle for conventional business ecosystems, leading to isolation of inspired innovations for the poor and by the poor. This dream of a successful quasi-social corporation is still in infancy but its success will largely depend on Indian enterprises that will not overlook grassroots innovators with their trademark cost-effective and sustainable technologies.

The recent tie-up between Tata-Agrico and NIF and frequent technology transfers between interested enterprises and NIF reiterates the identification and effective utilization of emerging niche innovations and technologies. However, without explicit policy moves in that direction, IIIF is in danger of falling a few steps behind its inclusion agenda.

Prakash Vyas exposes another loophole, especially concerning patents for grassroots innovations. He cites the recent fee hike for application and early publication of patents which can become hindrances to the economically challenged. The grassroots food industry is especially vulnerable given the amount of time it takes to get the patent, Vyas points out.

Patent famine

Deputy Controller of Patents & Designs G P Roy of the Intellectual Property Office in Chennai blames the backlog of cases extending back to five years for the inability to speed up the process. “Last year, we received 16,441 patent applications at the Chennai patent office alone,” Roy adds. The need for more hands at the patent offices is ironically made clear to applicants like Chary who can do nothing but lament the state of the system.

Says Chary: "I have expanded my business with a little help from NIF, Ahmedabad, while fighting many who tried to copy my technology in the interim." He received Rs 1 lakh from the Micro Venture Innovation Fund (MVIF) of the NIF in 2007 and is patiently awaiting the patent for his IKYA-ReD technology which was granted six years ago.

NIF, which has so far filed nearly 500 patent applications from grassroots innovators, has succeeded in getting patents for only 7 per cent of these applciations. Nearly 20 per cent of applicants have filed requests for examination of their innovations.

Using the IPAIRS patent search engine of the government, it has been found that some of these requests date back to 2008 and are still pending consideration. Such situations highlight an urgent need to fix a timeframe after a request for examination is sought by the applicant along with implementation of effective measures to clear the backlogs.

"I got my products certified at CPRI, Bangalore privately, since I did not hear from either NIF or from the Chennai patent office since December 2010 after filing a request for examination," says Chary, adding that his priorities have changed from getting a patent to giving employment opportunities, especially to those possessing BPL cards. A job can save such sections of society from certain death, he says. Chary now gives direct employment to more than 100 people and a few distributors spread across Andhra Pradesh and Orissa.

Vyas says that the market for the food industry is nowhere near saturation point and innovative products have become the norm to sustain oneself against competition. Vyas not only finds distributors for his products at different expos, but also people eager for mutual technology exchange.

Earlier, grassroots innovators in India lacked either funding or the entrepreneurial spirit. But with more and more grassroots innovators becoming social entrepreneurs, they have the potential to significantly contribute to India’s inclusive growth.

Only a fraction of the patent boom recorded in India in the past decade comes from resident-filed applications; however, methods to protect the rights of this 11 per cent of the patent population and nurture it are yet to be perfected.

Truly inclusive innovation can’t take place without inspired innovations -- with or without value additions – being permitted entry into the entrepreneurial ecosystem. Innovative solutions for those at the bottom of the pyramid can’t be just a top-down social enterprise. Whether grassroots entrepreneurs define this decade of innovation will depend on how far those dwelling at the top of the pyramid recognize ideas rising from the abyss.

The writer is a doctor-scientist interested in science and innovation paradigms in India. He is currently post-doctoral fellow in neurosciences at the Miller School of Medicine, University of Miami, Florida.