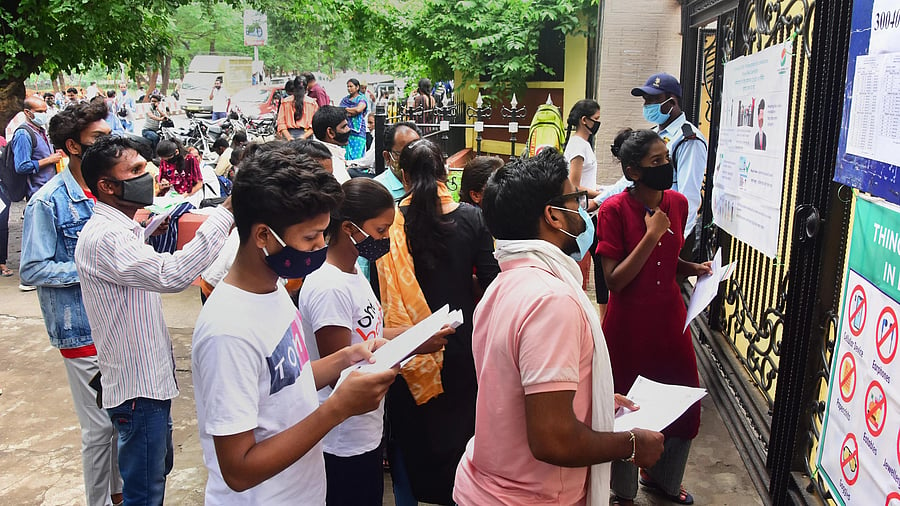

Aspirants look for their seat number to enter an examination centre for appearing in National Eligibility cum Entrance Test (NEET UG 2021) in Jabalpur.

Credit: PTI photo

In the southern corner of the country, on the outskirts of Thiruvananthapuram, a government-run school has preserved a partially burned wooden bench for posterity. Though lacking the aesthetics of a 21st-century private school furniture, the humble bench carries with it a tale of revolt and perseverance.

Over a century ago, this school in Ooruttambalam village—then part of the princely state of Travancore — was the flashpoint of an agitation for Dalit education rights. Heralding a new chapter in the struggle of the ‘untouchables’ against inequality, renowned social reformer Ayyankali, hailing from the Pulaya community, had led Kerala’s first agricultural strike in 1914 after the school authorities denied admission to a Dalit girl named Panchami.

As the agitating Dalits — mostly landless agricultural laborers— refused to work in fields, dominant caste groups responded brutally and burnt down the school. The semi-charred bench in the school, renamed in 2022 as the Ayyankali-Panchami Upper Primary School, is the only remaining physical proof of the historic struggle. What encouraged the Dalits to undergo misery and hunger was their belief in the power of education in weeding out inequality.

Several decades before Ayyankali’s revolt, the social reformer couple Jyotiba Phule and Savitribai Phule had fought for the education of girls. Similarly, Dr B R Ambedkar, as a member of the Viceroy’s Executive Council, made the British colonial regime introduce reservations in public services in 1943 and post-matric scholarships in 1944. The scholarship scheme, though in a watered-down form, runs even today.

What Ayyankali, the Phules, and Ambedkar believed was that equitable access to education is the primary right of any human. This was particularly important in India, where access to education was traditionally denied to the ‘untouchables’, backward classes and women by the caste system intertwined with patriarchy.

While the post-Independence caste-based affirmative action has enabled relatively equitable access to government-run higher education institutions (HEIs), the mushrooming of private HEIs has once again brought the ‘access’ question to the forefront.

It may be noted that the pre-Independence push for social justice did not transition smoothly after 1947. The first blow was in 1951, when the Supreme Court, in the Champakam Dorairajan case, abolished caste-based reservations in educational institutions, citing a violation of Article 15, which prohibits discrimination. This led to the First Amendment of the Constitution.

A furious Ambedkar was instrumental in drafting Article 15(4), which provides special provisions for “socially and educationally backward classes” such as SCs and STs. However, the backward classes were still not able to access the HEIs, including the IITs and IIMs, which by the 1990s had become the focus of the middle-class.

It wasn’t until 2006 that Article 15(5)—introduced via the 93rd Constitutional Amendment—enabled reservations in the Centre’s HEIs for backward classes.

By this time, the floodgates of private education had been opened in the country, particularly in high-demand fields such as medicine, engineering, management, and pharmaceuticals. The number of private HEIs increased from 10 to 145 since 2006. According to the India Brand Equity Foundation, under the Department of Commerce, the education sector attracted $9.9 billion in FDI between 2000 and 2024. India’s higher education market, valued at $68 billion in 2024, is projected to reach $137 billion by 2033.

It is at this juncture that a recent recommendation of the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Education, Women, Children, Youth and Sports—to introduce reservations for SC, ST, and OBC communities in private HEIs—has rekindled a long-standing debate.

The recommendation also revisits the conflict in the TMA Pai judgment of 2002 — in which the Supreme Court granted private institutions autonomy under Article 19 (1) (g), by interpreting the running of education institutions under the definition of business — with Article 15 (5) introduced by the UPA in 2006, which allows a state to impose reservations in private institutions. Notably, no state or central government since 2006 has made any law for such reservations.

It is yet to be seen if any government will come forward to provide reservations in private HEIs. However, taking cues from Ambedkar’s idea of post-matric scholarships, an education grant shall be given to SC, ST and OBC students, along with the new category Economically Weaker Sections, if the government plans to open up reservation in private HEIs.

Such a measure would ensure diversity and inclusion in top-tier private HEIs. Since many of these charge hefty fees, the government must be willing to fund the education of deserving candidates.

This would require the government to increase its current allocation of 4% of GDP to education to 6%, a giant leap of adding $83 bn to ensure universal access to all educational institutions for all, by the mandate of Article 15(5).

The struggle of erstwhile reformers for equitable access to education can be taken forward only if the inequality in higher education vis-a-vis private HEIs is addressed.

(Author is an Associate Professor in Jindal Global Law School, OP Jindal Global University, Haryana)