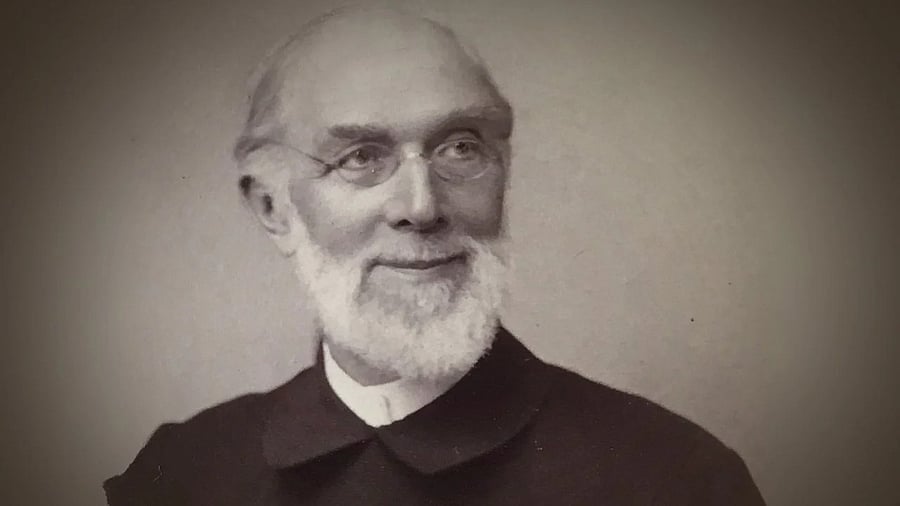

An 80-minute film provides fresh insights into the life and times of Ferdinand Kittel (1832-1903), the German who compiled the first ever Kannada-English dictionary. Published in 1895 and in print to this day, the dictionary serves as a definitive guide to writers, linguists, translators and lay people.

Kittel’s story is extraordinary. A member of the Basel Mission, he sailed to India in 1853, and began learning Kannada for his evangelism. When he stepped out, he was disarmed by how the poor approached spirituality. “Our god is in our village.” a shepherd he meets tells him. “But I don’t know a thing about heaven.” Already proficient in German, French, English, Hebrew, Greek and Latin, Kittel fell in love with Kannada and embarked on a scholarly pursuit that would last a lifetime.

‘The Word and the Teacher’, written and directed by Prashant Pandit and screened at Bangalore International Centre last Sunday, tells Kittel’s story in Kittel’s voice. Rolfe Hocke, the voice actor who plays Kittel, narrates the story in Kannada, German and English. Pandit, a Mysuru-based software engineer, had edited several films before he took up this project. He travelled to many locations in India and Germany, using his own resources and taking help from friends. As he retraced Kittel’s steps, he got access to his letters, many of which reflect the personal and professional turmoil he lived through.

Kittel spent 40 of his 71 years in India. His monumental work in lexicography has earned him a place among the greatest scholars of all time in any language, and his work in Kannada makes him one of the tallest contributors to Indian language and literature studies. The Word and the Teacher reveals some fascinating, little known aspects of his life. When his superiors stopped his grants, saying they couldn’t afford a missionary who was doing no missionary work, he returned heartbroken to Germany. A British judge and the king of Mysuru, aware of the phenomenal work he had embarked on, made generous grants and got him to return to India and complete his work. Kittel also wrote hymns in Kannada and set them to music. He collected palm-leaf manuscripts of Shabdamanidarpana, Kesiraja’s 13th century book on Kannada grammar, edited it with a commentary, and got it printed. He translated a work by the Kannada grammarian Nagavarma II (11-12th century), and compiled a short dictionary for school children.

Pandit’s film is a heartfelt tribute to Kittel, and it captures the period with an eye for detail. Kittel accomplished so much in an era with no electricity. He travelled long distances by bullock cart--the railways came to Mangaluru, where he lived for many years, four years after his passing. A college in Dharwad is named after him, and a statue near Mayo Hall in Bengaluru honours his memory.

Kittel’s enduring contributions call for more celebration, perhaps with a richly mounted feature film. Pandit’s film, which he hopes to show across venues in Karnataka, points to many interesting possibilities.