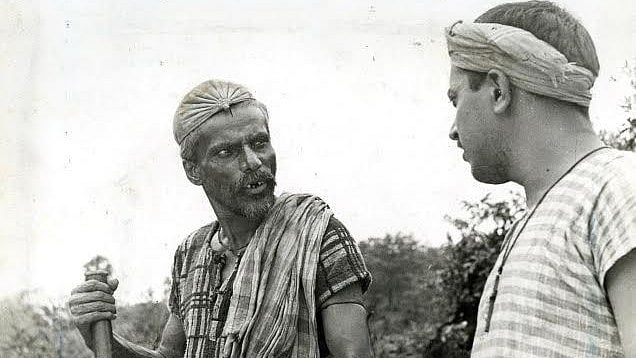

Two distant cinematic events, somehow related, have become accidentally relevant for the moment. Apart from ‘Kantara: Chapter 1’, a prequel of the hit 2022 film, due for release on October 2, the year marks the 50th anniversary of B V Karanth’s ‘Chomana Dudi’ (1975). The latter is a Swarna Kamal winner for Best Film and one of the most important Kannada films ever made. Both ‘Kantara’ and Karanth’s film invoke Panjurli Daiva a deity from the coastal belt that takes the shape of a boar though in different ways. There was some criticism of ‘Kantara’ from liberal circles accusing it of appropriating tribal belief on behalf of mainstream Hinduism, in the ascendant since 2014. I don’t think this criticism was pertinent because ‘mainstream’ Hinduism is itself an accretion of various practices, many of them formerly tribal. The different attributes/names of a god like Krishna (child, lover and charioteer) are arguably due to the amalgamation of different cults with separate deities into a single deity with a checkered history. There was hence a child Krishna but perhaps not a child Rama although the latter has been consecrated in Ayodhya on the supposition that all adults must once have been children. The deity Panjurli may hence be both a local deity and the boar (Varaha) as an avatar of Vishnu.

‘Kantara’ and ‘Chomana Dudi’ both invoke Panjurli but their attitude to the deity is different. ‘Kantara’, being part of popular culture, is addressing a much bigger public with belief in Panjurli while ‘Chomana Dudi’ is an art film that draws from an official rationalist initiative. Modern Indian literature and cinema after 1947 are products of Nehruvian policy that tried to create a modern nation founded on scientific principles. If people of my age, born in the 1950s, reflect upon the school education imparted to them as children, they immediately recollect stories or other texts in which religious practice was equated with superstition. Since secularism was also a credo in this education and the faiths of the minorities needed to be respected, Christian or Muslim belief was not similarly discredited. And it was mainly the beliefs of the majority that were subjected to such hostile scrutiny as ‘superstition’ — I recollect the dastardly deeds of the Vedic god Indra particularly perplexing me.

The result was that modern literature and art cinema did not have religious aspects — as literature and cinema across the world are allowed. Popular cinema and low-brow literature were different since they did not constitute what was officially defined as national culture. We therefore also had Chandamama and regional mythological films that defied Nehruvian policy. The mainstream Hindi cinema was more a part of national culture and for this reason there are few mythological narratives after 1947. Exceptions were only in the ‘B’ category — films like ‘Jai Santoshi Maa’ (1975) and horror cinema that deals with the occult. ‘B’ category cinema caters to a less educated clientele, once from the small towns, while modern literature and art cinema are only for the highly literate. We may note here that this sense of rationality as the basis of national culture was also the official policy in Communist societies. The fact that religious belief is today stronger there than rationality is one of the ironies of history.

Nehruvian cultural/education policy, in some ways, depleted culture. The emphasis on science/technology was necessary for nation building itself but the understanding that science inculcates the spirit of enquiry was perhaps misplaced. Brahminism — with its faith in an original infallible text — had placed its emphasis on rote learning rather than on questioning and that is how science and mathematics were essentially absorbed. Ironically, many intellectuals in India, like the Marxists, also partial to rationality, treat the texts they adulate as the ‘truth’ rather than ideas open to falsification, implying a ‘superstitious’ approach to received knowledge.

Nehruvian policy, contrary to expectations, did not help inculcate a spirit of enquiry even among educated Indians but over the years its initiatives gradually lost their sheen. Nehruvian history writing, for instance, is being contested — though not dispassionately but hotly by alternate viewpoints, through assertions even more questionable. As an instance of the growing conflict, archaeology is a contested site where the Centre and the Tamil Nadu government are taking sides, casting doubt on the discipline itself. One could not, two decades ago, have imagined political parties vehemently supporting conflicting narratives of ancient India! Traditional beliefs, buttressed by politics, have also emerged much stronger than one might have imagined.

Returning to ‘Chomana Dudi’ and ‘Kantara’ — the two films represent opposite treatments of religious/occult belief. The first, with its discourse on rationality, saw religious belief as akin to superstition and all those practicing it as backward. ‘Kantara’ belongs to a new category of cinema that uses the services of technology to actually create a plausible world in which occult elements have a prominent foothold. ‘Kantara: Chapter 1’, according to the advance publicity, is a very expensive production and one guesses that much of this expense was incurred to make Panjurli seem real when ‘Chomana Dudi’ once told us that Panjurli was only the retrograde belief of backward people. In other words scientific advances are today being employed to promote the irrational!

(The author is a well-known film critic)