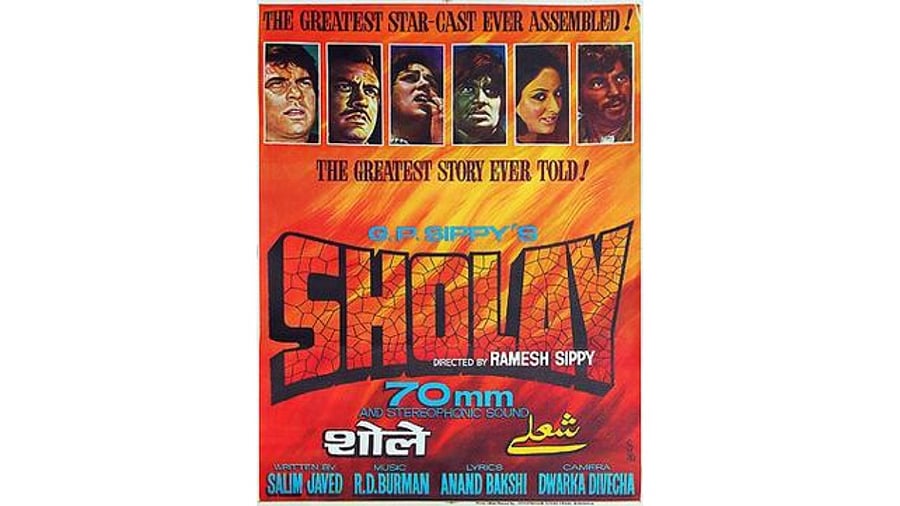

Sholay Poster

Credit: United Producers, Sippy Films

Ramesh Sippy’s Sholay (1975) is a rare film that can be discussed and analysed without first having to describe it. There is perhaps no better known Indian film even 50 years after its release.

Everyone is also aware of its attractions, the dosti between Dharmendra and Amitabh, the romance between Dharmendra (Veeru) and Hema Malini (Basanti) and the unrequited one between Amitabh (Jai) and Jaya (Radha). Sanjeev Kumar as the shrouded and armless Thakur Baldev Singh and Amjad Khan as Gabbar Singh, the most memorable villain ever from Bollywood still do not complete the picture since there are also three over-the-top comic performances from Asrani, Keshto Mukherjee and Jagdeep. Regardless of its unabashed borrowings from world cinema, (notably Sergio Leone’s ‘Once Upon a Time in the West’) ‘Sholay’ is a popular classic that has withstood the test of time, almost heroically. But it makes little sense to once again praise its various aspects and I will examine some motifs that could relate to its basis in Indira Gandhi’s most fearsome period, shortly after declaring the Emergency.

The first motif of importance is that of petty criminals enlisted by the law to fight a larger evil which first appeared in ‘Zanjeer’ (1973) where the owner of a gambling den (Pran) joins a policeman (Amitabh) to fight the dastardly villain (Ajit). What the motif suggests is the new implications of legality/justice when Indira Gandhi envisaged redefining the law through a ‘committed judiciary’ sensitive to the needs of the people. Film theorists have noted that the petty criminal represents the marginalised in Hindi cinema and enlisting them to fight national enemies is to draw them into the mainstream after long being marginalised figures; Jai and Veeru are enlisted for a noble purpose by the (former) police Inspector Thakur Baldev Singh because of their sterling qualities.

The second motif is the larger evil represented by Gabbar and such figures proliferated in the 1970s. The villains of the 1970s, those played mostly by Ajit, are different from the earlier socially-grounded ones like moneylenders, princely stepbrothers or zamindars in which their motivations are clouded. We never know, for instance, much about Gabbar, not even why his men chase the train when there is nothing on it. The earlier villains were part of a narrative with correspondence in social conflicts but not so the Shakaals or Gabbars of the 1970s. The lack of faith of the films in legitimacy of these villains is best demonstrated by ‘Bobby’ where he is given the same name as the actor (Prem Chopra); the villain is simply used to resolve a narrative that resists resolution.

Indira Gandhi’s era was one that was confusing to the public since her rhetoric named strange adversaries (like the CIA, the judiciary, wealthy people) different from before. ‘Sholay’’s narrative tried to knit the social fabric through their presence as a common adversary. My proposition is that Gabbar is only a conjunctive device — with no social equivalence — to bring socially diverse groups like the police, the landed aristocracy, petty criminals and the rural public into a single narrative. This mirrors a reconciliation of various social groups within a secular-socialist framework; ‘secular’ is made especially important and Gabbar kills Ahmed (Sachin) to suggest it. In ‘Yaadon Ki Baraat’ (1973), the villain (Ajit) does what an earthquake had done in ‘Waqt’ (1965), which has virtually the same story otherwise — to bring various social categories together through the story of a family’s break-up and reunion. We may also note that the villain gives the various participants a common larger purpose which goes beyond the family reunion.

To return to ‘Sholay’, its parts add up to much more that its whole and the various components have to be savoured independently as separate stories without our making too much of an effort to bring them coherently together. Gabbar, perhaps the crowning achievement of the film, especially with regard to his imprint upon public memory, may be a creation owing much to the actor who plays him. But, Gabbar, while being a dacoit, dresses in uniform and not in the traditional clothes of a dacoit as Jabbar Singh in ‘Mera Gaon Mera Desh’ (1971), (which is also about a petty criminal enlisted by a policeman to fight a larger evil). Gabbar’s brutal acts are indiscriminate and he arguably mimics uniformed authority that need not account for itself. ‘Ab tera kya hoga Kaliya?’ even implies that he represents impersonal authority since he is wondering about Kaliya’s fate when just about to liquidate him! The film was released during the Emergency and one is tempted to see an association between Gabbar and impersonal official tyranny. It is also significant that Thakur Baldev Singh operates alone and is not seen with the subordinates/constables that police inspectors are normally seen with in cinema. Making him an ex-policeman may also be to prevent us from seeing him as embodying the state.

Multi-starrer films are not simply a way of milking a story for its commercial potential and since each star represents a social type they are also a way of constructing a narrative that incorporates diverse social elements to help the public make sense of the happenings in the polity. Multi-starrers proliferate when the political situation is complex and difficult to fully comprehend, as it was in the 1970s.

(The author is a well-known film critic)