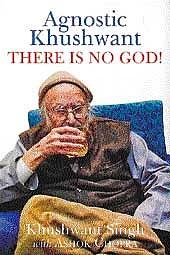

Agnostic khushwant: there is no god

Khushwant Singh with Ashok Chopra

Hay House

2011, pp 246

Rs. 299

He starts from the premise that belief in God or religion need not make one a good or bad citizen. Down the ages, religion has done more harm to humanity than good by generating more hatred than love. Hence “we have to evolve a new religion that avoids the pitfalls of outworn creeds,” he argues.

This new religion, based on work ethics and prayer, will be replaced by good work. It won’t have any place for godmen or astrologers and family planning will be compulsory. It will prevent causing hurt to all living things and all efforts will be made to protect the environment.

Agnostic Khushwant: There is no God is a collection of essays that reflect the

prolific writer’s views on religion and God. What makes the volume readable is the author’s success in simplifying the mystique surrounding belief in God and religion.

Khushwant finds all scriptures unscientific, repetitive and tediously boring. He wants scriptures to be treated as historical documents, read for their literary quality and understood, but not worshipped. His assessment is that those who spend maximum time before their favourite deity are those who seek forgiveness for their evil deeds.

He faults Indians for wasting more time in rituals than with people. He explores his agnosticism not irreverently, but with firm hands of logic. He questions the relevance of rituals and the stranglehold of priests and god-men. He takes on bigots and blind beliefs based on miracles, holy men and pilgrimage. Most of what he says may not be palatable to believers.

The most edifying chapters of the book are those that bring out the beauty of the Quran and the Granth Sahib with passing references to the Bhagawad Gita and the Bible. Quoting extensively from the Quran and the Granth Sahib, Khushwant Singh avers that passages can be read for their moral message or for their literary

excellence.

He sets apart an entire chapter to dispel anti-Muslim prejudices, while another

explains the significance of Ramzan fast. Bulk of the book is devoted to tenets of Sikhism. His exhaustive analysis of the Adi Granth, Sikh prayers and glowing account of the life and times of Guru Nanak and Guru Gobind Singh reflect his mastery over Sikh history and provides a wealth of information to the reader. He decries the custom of taking out religious processions that often lead to communal conflicts.

The chapter Religion versus morality focuses on the need to reunite morality and religion. The diminishing role of religion in India provides an opportunity to “give a totally modern reorientation to religion or scrap it altogether.” Khushwant Singh lives up to his reputation of coming up with something controversial in every book.

The itch to provoke is inevitable. “What we need to demolish are God, prophets, scriptures, prayer and places of worship’’, he asserts. His assessment of Swami Vivekananda is not very flattering. “He was a good orator but by no means as great a thinker as his admirers make him out to be.’’ He is dismissive of Vivekananda’s Chicago speech and the prophecy about the collapse of “material-minded West” and the renaissance of “spiritual- minded East.” He is impressed with Dalai Lama, who is described as a man of peace.

Khushwant remains a Sikh first and last. Some consider this self-proclaimed

agnostic a devout Sikh who wears his identity on his sleeve. He maintains the

distinctive symbols of his faith intact and loves listening to Gurbani every day.

Remember the near hysterical remarks that he made in the aftermath of Operation Blue Star. He was outraged when his son cut his hair. He loves counting how many Sikhs are in corridors of power. He is thrilled when Harbhajan bowls well.

He refers to a leading astrologer who arranged his daughter’s marriage after carefully going through the horoscopes of the bride and the bridegroom. “The marriage lasted only a few months.”

Despite the many delightful anecdotes dished out to buttress his staunch refusal to believe in institutionalised religion, this is not the vintage Sardar noted for his caustic remarks on the high and mighty, giving vent to his biases and prejudices.

He is at his best in pricking inflated egos. This time, there is less of him. There may not be many takers for his sweeping generalisations and advocacy for a new religion sans God, but none can ignore what he writes. The main selling point is the lucid style characterised by the unique felicity of expression that has made his columns immensely popular. On that count, this volume too doesn’t disappoint the reader.