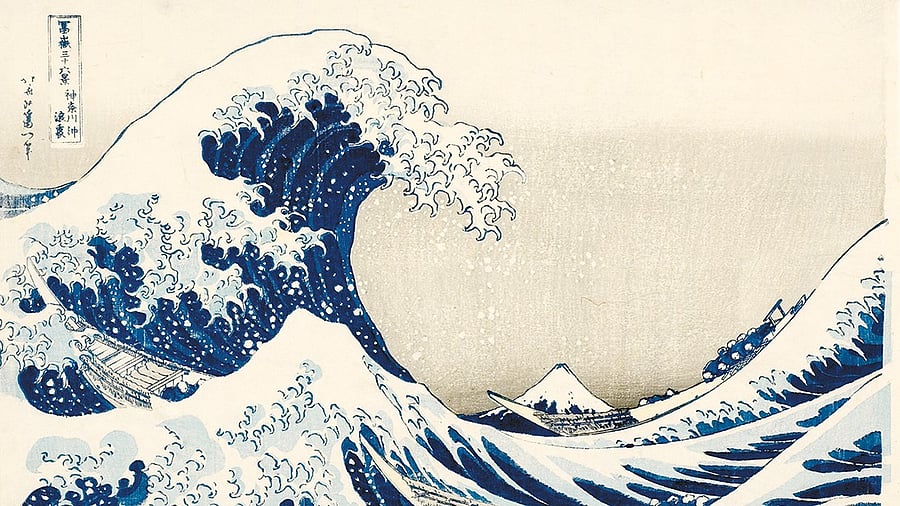

The Great Wave.

Credit: Pushkar V

Japanese artist Katsushika Hokusai’s The Great Wave off Kanagawa is Japan’s most famous painting: a storm of blue and claw-like waves that the whole world seems to recognise at a glance. Like the Mona Lisa for France, Las Meninas for Spain, or Raja Ravi Varma’s Shakuntala for India, it has become more than a masterpiece; a single image that quietly carries a nation’s imagination.

At the end of November 2025, that familiar wave rose again. This time it surged through a Hong Kong auction room, where Sotheby’s offered a rare early impression from Hokusai’s Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji series. The print, titled “Under the Wave off Kanagawa,” sold for approximately $2.8 million, setting a new auction record for this image. It originated from the Okada Museum of Art in Hakone, a small town renowned for its picturesque views of the iconic Mount Fuji in Japan.

Many waves, many homes

Unlike a single painting such as the Mona Lisa, The Great Wave off Kanagawa was printed many times from carved woodblocks, meaning there is no lone “original.” Museums from New York to London and Tokyo hold prized impressions, each slightly different in colour and sharpness, some with deeper Prussian blue, others softened by time. At the Shimane Art Museum in Matsue (pictured), one copy belongs to a Japanese art collection shown only in rotation.

Curators at the Shimane Art Museum say that Hokusai works are brought out for short public runs, about four weeks a year, and then returned to dark storage so they can rest between showings, because light can quickly fade these delicate papers. The Sumida Hokusai Museum in Tokyo follows a similar rhythm, using rotating exhibitions and replicas to tell his story while carefully rationing the exposure of fragile originals. This means there is no single shrine to The Great Wave; instead, its “many originals” live scattered around the globe, appearing and disappearing like the tides in the painting.

Indian professor’s suitcase

Jitendra V Singh, an India-born management professor working in the United States, spent years building a set of Hokusai’s Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, buying prints that had travelled across continents. In 2024, Christie’s sold his complete set in New York for about $3.56 million, at the time the highest price ever achieved for Hokusai prints as a group. For a while, an Indian professor living in America was the guardian of Fuji, keeping the mountain safe in boxes and portfolios far from Japan.

Hokusai’s restless life

Katsushika Hokusai was born in 1760 in Edo, now Tokyo, and died in 1849, after a working life that stretched nearly 90 years. He changed his artistic name more than 30 times and moved house over 90 times, chasing commissions, escaping debts, and starting over again and again. His style belonged to ukiyo-e, the “pictures of the floating world,” but he pushed beyond actors and courtesans to landscapes, storms, ghosts, and everyday workers.

His innovation lay in combining traditional Japanese block printing with European ideas of perspective, allowing him to create compositions that felt modern and dynamic. His prints travelled west and went on to influence artists such as Monet and Degas; Vincent van Gogh admired Hokusai’s work.

Hokusai’s Fuji series, begun around 1830, promised 36 views but eventually grew to 46, with 10 extra designs added after its initial success. The Great Wave is just one of these, placing the sacred mountain as a small, steady triangle beyond the chaos of the sea. Hokusai drew the image, a carver sliced it into blocks, and printers worked the paper and ink, with publishers financing and selling the prints.

The Prussian blue pigment, newly imported to Japan, was deep and vivid, giving the sea and sky their striking colour and helping the prints stand out in the crowded Edo market. The cheap paper and mass printing meant these works were once affordable to common people — closer to posters than luxury treasures. That humble origin makes today’s million-dollar prices feel all the more dramatic.

A wave in pop culture

Today, The Great Wave appears on T-shirts, tattoos, the wave emoji, and even on the back of the 1,000-yen banknote. Museums report that younger visitors often recognise the image before they know Hokusai’s name, encountering it not through art history books but via anime, memes, and phone wallpapers.

That great curl of water is no longer just a scene. It has become a shared memory. It carries with it the story of an old artist who kept reinventing himself, the mountain he adored, and the worlds he shaped without ever leaving Japan. Hokusai may have lived in a time of isolation, but his creation refuses to stay still. The wave continues to rise endlessly, reminding us that art does not fade. It simply keeps moving, carrying all of us with it.