Credit: Special Arrangement

In his book, Room for Wonder: Indian Painting during the British Period 1760–1880 (The American Federation of Arts, 1978), the American scholar and curator of Indian art, Stuart Cary Welch Jr, contextualises how “the British propensities for exploration and documentation” and “their inquisitiveness and collectomania were rewarded by the growth of a new idiom of Indian painting, usually known as Company School”.

Company School, or the more popular term “Company Painting”, came to be used “freely”, according to the Indian art historian and critic B N Goswamy, in the 1930s. While there can be a debate on who coined the term — whether it was Rai Krishnadas or Ishwari Prasad, or someone else — “the ‘style’, if it can be so called, was soon everywhere”, Goswamy notes in an essay.

To popularise what the Company Painting era produced and how it helped shape the journey of Indian art, DAG (formerly Delhi Art Gallery) has an exhibition titled A Treasury of Life: Indian Company Paintings 1790–1835 on display until July 5, 2025. Curated by art historian and writer Giles Tillotson, who’s also Senior Vice President, DAG, the exhibition “builds” on the gallery’s earlier one titled Forgotten Masters: Indian Painting for the East India Company, “expanding the conversation to highlight the full scope of Company painting.”

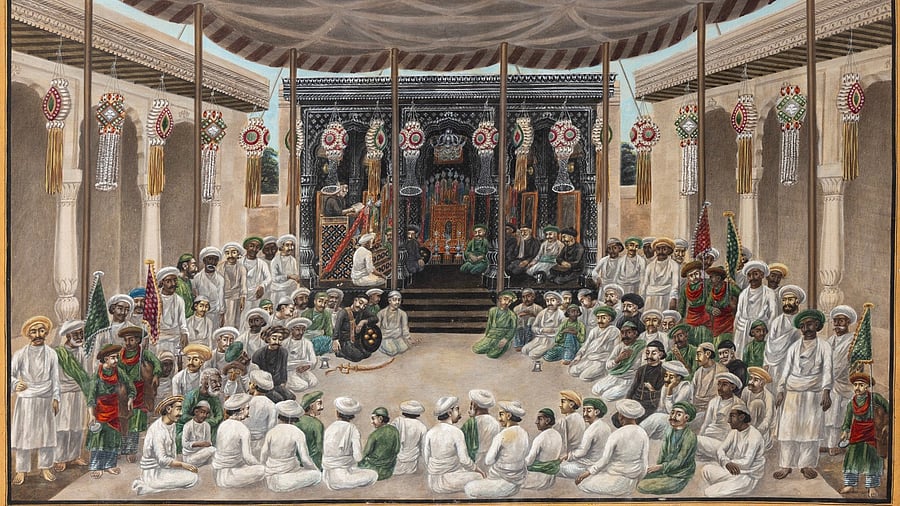

From Prayers and Recitations at the Muharram Festival (1820–30) to Fete des Hindous appellée Kales Pojas [Hindu Festival called Kali Puja] (early 19th century) and from Chestnut-vented Nuthatch (Sitta nagaensis), 1810, to Arsenic Bush (Senna septemrionalis), Ivy Gourd (Coccinia grandis) and Bitter Gourd (Momordica charantia), 1795, the collection features some stellar works both by unknown artists from across India to well-known figures from Chuni Lal to Sewak Ram, and Sita Ram. But because this collection is a window to understanding the expansive Company School era, and doesn’t capture it in its entirety, I believe the artworks on display draw from influences of the artists’ predecessors like Bhawani Das and Shaykh Zayn-al-Din of Patna and Calcutta respectively though nothing like that is hinted at in the curatorial notes.

But what Tilloston’s curation reflects is something that Cary Welch Jr had summarised around half a century ago in his book about the Company School: “Natural history painters, for instance, became especially skilled at rendering quills, feathers, blossoms, or the proportions of animals; while other artists devoted their lives to documenting views along the Ganges River.” Therefore, it feels logical to see the paintings organised at DAG based on their inspiration — India’s flora and fauna, architecture, rural landscape views and Indian customs and trades. The curatorial note at DAG notes that the proliferation of the paintings depicting sacrificial killings or the congregation of people around some festival or the other could’ve never seen the light of day had it not been for the foreign patrons’ “demand”. The note doesn’t pin anything on the gaze, though.

Moreover, there are several artworks featuring Mughal-era monuments, which makes one think why Indians were painting them when William Hodges, the masterful landscape artist, was brought especially from London to Madras towards the end of the 18th century to document the everyday Indian life (to be taken back to the UK by the patrons as mementos). Not only him, but there were also artists like Thomas Daniell, William Daniell, and George Chinnery, all of whom were trying to make the most of the opportunity. The answer, which the curatorial note also acknowledges, is that their paintings would cost a lot to the patrons. However, one can also find this interesting note in Cary Welch Jr’s book: “Seeing an English amateur painter at work, an Indian gentleman approached him, ‘Why, sir,’ he asked, ‘are you doing that? Could you not employ some Indian to do it for you better?’ Although many sahibs and memsahibs painted their own pictures (and a few were extremely talented), most took the view of the Indian gentleman.”

With this context in mind, through this exhibition, one can engage with the Company Painting chapter with a renewed vigour. But not without ignoring the legacy of British colonialism. For example, here’s what the Assistant Professor at the Department of History, Shivaji College, University of Delhi, Sonal Singh, points out: “[William] Hodges’ much-famed Ghats of Banaras made during the conflict with Warren Hastings, when he accompanied him, is in sharp contrast to the arrest of Chait Singh and the resulting battle. Even when the subject on the canvas was a battle scene, it conformed to imperial ideology, valourising the sacrifices of the Company in the wake of ‘atrocities’ by the natives.”

This is to say that gaze matters. Not only that of the consumers lining up to view and collect art, but also that of the artworks’ producers. Perhaps this is how viewing artworks enriches us: if only we hear the stories they seem to be telling us from the background.