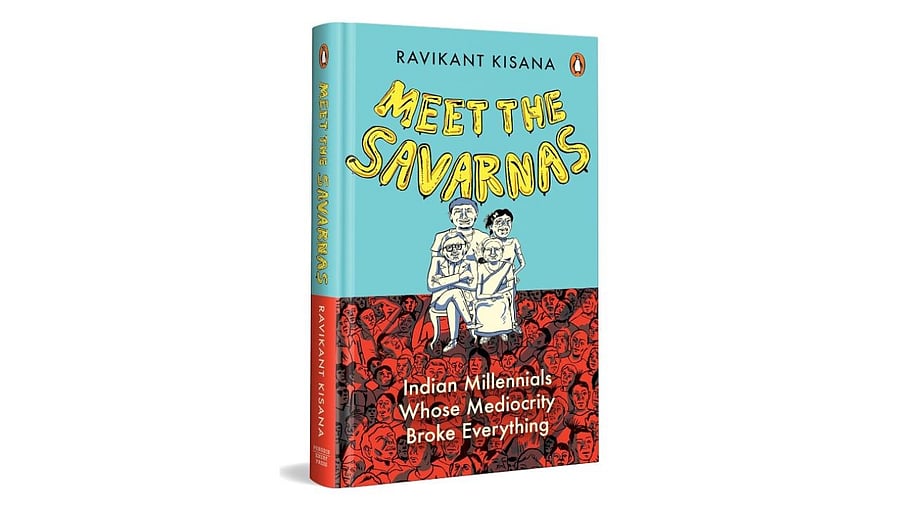

Meet the Savarnas

Credit: Special Arrangement

Times may have changed, but the stranglehold of caste on the Indian psyche refuses to loosen. A recent newspaper report on a Dalit trainee pilot being asked by senior pilots to stitch shoes is telling. Efforts of the upwardly mobile from the oppressed classes to break the barriers often invite hostility and prejudice. Not only does caste oppression receive scant attention from those in power, but urban elites are also dismissive and indifferent to this social malaise.

Here is a book that challenges the traditional notion of the caste system and depicts the Savarnas as a distinct social group. Meet the Savarnas: Indian Millennials Whose Mediocrity Broke Everything by Ravikant Kisana is a critique of the abhorrent social system that has shaped India and stymied its progress. Unlike other books on caste, this one holds a mirror to Savarnas (privileged castes) and examines their self-image, warts and all. In other words, the book looks closely at a tiny section of Indians who hold most of its wealth and power, but ignore their inherent caste privilege: this is an earnest attempt to document the world of Savarnas, their concerns, crises and culture.

In a quintessential expression of Ambedkarite angst, Ravikant says, “They own everything.” He contends that caste as a privilege is not understood well and argues that the intergenerational privileges perpetuated Savarna domination for centuries. Ravikant, an associate professor based in Hyderabad, terms Savarna cultural values self-serving at the expense of those excluded and also raises questions on how caste elites respond to challenges of modernity and neoliberal policies. Citing the reported denial of entry of President Draupadi Murmu and her predecessor Ramnath Kovind to certain temples, Ravikant points out: “Even the President of India can be denied access to caste-sanctified spaces.” The book is a critical review of our system of education, politics, businesses and government. The author has chosen three sectors to buttress his argument on caste discrimination — the economy, the workplace and higher education. Ravikant points out that in a society where caste and class intertwine, wealth creation is not solely based on merit, talent or hard work: Crony capitalism thrives on patronage, quid pro quo, hijacking regulatory processes, and manipulating policies facilitated by caste and kinship networks. He also cites Bania communities’ domination of the economy for over 500 years and argues that in Narendra Modi, corporate India has found their best bet to promote Savarna interests.

Ravikant asserts that neo-liberalisation has not made any dent in caste hegemony and that India Inc. remains a social formation that is firmly in the hands of Savarnas. Caste has only mutated, taking different hues. Here is his take on the state of the Indian economy: ‘’a bloated underperforming economy that has failed to create jobs and income growth for the vast majority of its citizens,’’ whom he calls people living under the glass floor. He mocks the fantasy of a corporate caste supremacist society where the rupee is stronger than the dollar; where reign Starbucks and F1 races, bullet trains, and gleaming megacities.

In the early 2000s, India was expected to take a quantum leap forward and emerge as a rising superpower. Millennial professionals fresh out of B-schools and engineering colleges were to lead the way to realise the Great Indian Dream. But the dream has remained a dream. Ravikant points out that the golden generation was all Savarnas whose mediocrity stood in the way of the nation’s transformation.

He goes on to talk about the mushrooming of schools with international curricula and elite private universities, sans affirmative action. These, he terms as ‘an exclusionary system established via Savarna consensus’. The sky-high fees keep out students from marginalised castes. Right-wing intellectuals and sundry godmen are welcome always, though! It moulds a new generation of wealthy Gen Z students oblivious of Indian reality, their primary goal being migration to the West, he rues.

Other subjects covered in the book are love across caste lines, consequences of transgressions of caste boundaries in love and marriage and honour killings.

Some readers may find the plainspeak discomforting. The narrative equates English-speaking urban elites with the Savarnas, ignoring the rapid strides made by some intermediate castes. Also, the claim that Brahmin hegemony remains unchallenged in the domains of culture, arts, education and sports is debatable, although it is true that Dalit and OBC students have indeed faced bias at India’s premier institutions. Instances of caste discrimination and atrocities cited are mostly drawn from Hindi-speaking states notorious for caste oppression.