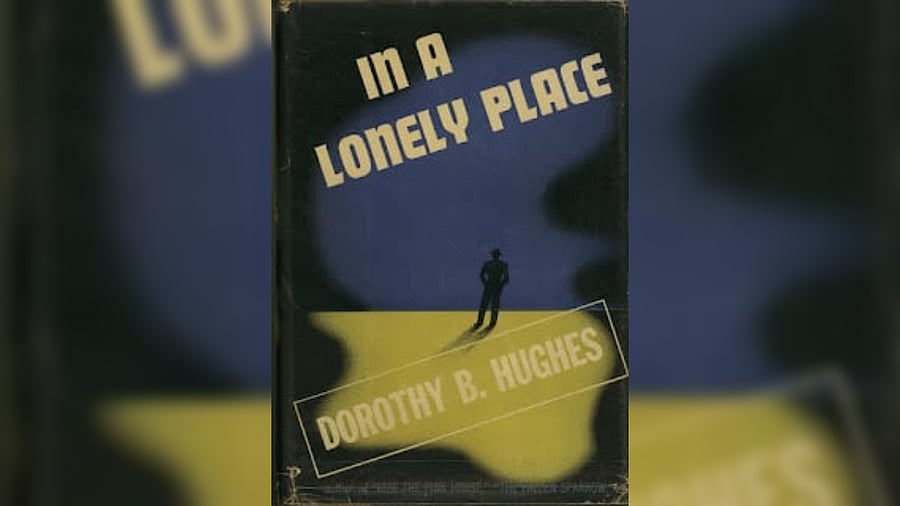

In A Lonely Place

Credit: Special arrangement

Serial killers seem to be having a cultural resurgence: from Ryan Murphy’s TV series to Mammooty’s and Madhuri Dixit’s recent onscreen turns, storytellers are once again plumbing the dark depths of the human psyche for our entertainment to varying degrees of success.

Last year also saw the publication of Caroline Fraser’s non-fiction book, Murderland, which investigated the possibility that lead poisoning in the air in north-west USA might have changed the brain chemistry of men like Ted Bundy, one of 20th century’s most prolific serial killers. There has been no conclusive scientific evidence explaining why these killers (the vast majority are men) do what they do, despite attempts to study them (as shown in the excellent David Fincher-produced, but sadly short-lived, Netflix series, Mindhunter).

Dorothy B Hughes’ classic hard-boiled crime novel, In a Lonely Place, first published in 1947 (a year before Bundy was born), is also about a serial killer, one who is revealed to us pretty early on as the main protagonist, Dix Steele. He has just moved to Los Angeles a couple of years after the end of the Second World War, in which he served as a fighter pilot. Lonely and hard-pressed for money, he’s moved into the apartment of an old Princeton acquaintance. He is also stalking and killing women on foggy nights across the city.

Steele’s close friend, Brub Nikolai, is a detective in the police department, and as the book begins, the two reestablish contact for the first time in years. (One of the delights of Hughes’ work is the names of the characters, one-syllable monikers that are made for noir tales.)

Steele is fascinated to discover Nikolai’s profession and, in an effort to get insight into the police investigation into the killings and hoping to stay one step ahead of the cops, tells his friend that he’d like to tag along for research on a book he’s supposedly writing. It’s a fiction that he’s sold to his benefactor, a Scrooge-ish uncle who was responsible for his upbringing. In quite a few serial killer stories, writers do tend to lean heavily on past traumas — often inflicted in childhood — as the root cause of their protagonists’ psychopathic tendencies. Hughes doesn’t provide Steele with such a backstory — he didn’t have a life of privilege, and though he did well in the war, he’s shown as being lost once the battles are done with and peace has prevailed.

What is clear, though, is that he needs to control women and has a deep-rooted rage that causes him to lash out when they don’t obey.

It’s this, the spine-chilling, forensic examination of a pathological misogynist and his way of thinking that makes In a Lonely Place such an indelible classic of the genre. Hughes doesn’t dwell on the violence or provide a lurid account of the victims’ suffering to build up a feeling of dread in the reader.

Instead, the book stands out from others of its type for the haunting depiction of the lonely streets and neighbourhoods of post-war Los Angeles, the fog so menacing that even though it’s decades later, you think you can hear the footsteps of the killer.

Hughes, who was a journalist and poet before she found success as a crime novelist, doesn’t romanticise murderers.

At one point, Steele and Nikolai discuss the nature of killers and the detectives who are on their trail: “‘The criminal doesn’t escape.’ Dix smiled wryly. Brub said, ‘I won’t say that. Although I honestly don’t think he ever does escape. He has to live with himself. He’s caught there in that lonely place…’”

In a Lonely Place was made into a classic noir film by Nicholas Ray, starring Humphrey Bogart in 1950, and while she was recognised as a master of crime writing in her lifetime, Hughes and her work seem to have faded from view in recent years.

Maybe now, when so many are trying to bring new perspectives and insights into some of the darkest human experiences, is the right time for a Hughes revival. And perhaps we can now appreciate her for the pioneering writer she was.

That One Book is a monthly column that does exactly what it says — it takes up one great classic and tells you why it is (still) great.

The author is a writer and communications professional. She blogs at saudha.substack.com