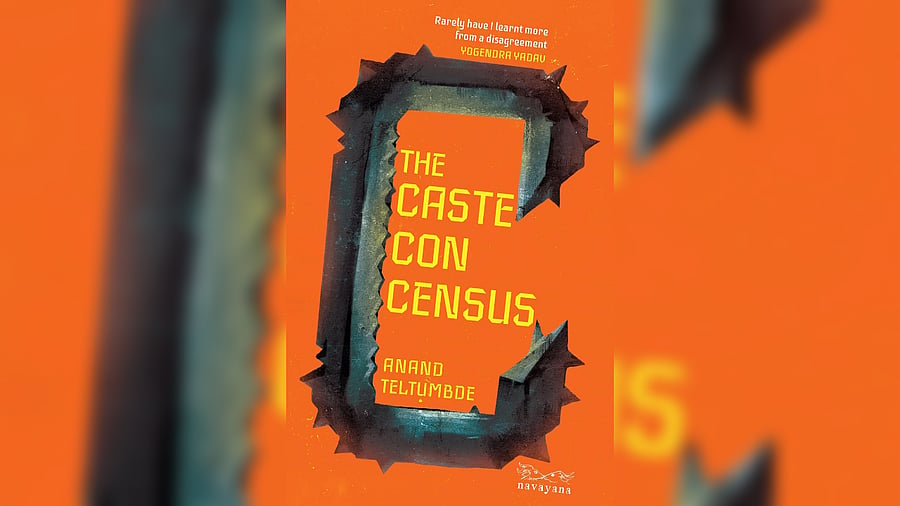

The Caste Con Census

Credit: Special arrangement

Is the census a neutral exercise or inherently political? Is caste data sacrosanct or susceptible to manipulation? Does it dismantle caste structures or reinforce them?? These are some questions that anti-caste proponent and public intellectual Anand Teltumbde poses in his latest work, The Caste Con Census.

The caste census has been highly polarising, with significant sections of the privileged shunning the very idea, while several oppressed communities have welcomed it. The BJP, which historically enjoys strong support from India’s upper castes, had slammed it as an “attempt to divide the Hindu society,” with PM Narendra Modi himself calling it an “Urban Naxal” idea. On the other hand, top Congress leader Rahul Gandhi has advocated for it and even championed the phrase ‘Jitni Abadi Utna Haq’ (the more the population, the more the rights).

This pattern was shaken when the BJP-led NDA government decided on April 30, 2025, to enumerate castes in the upcoming census. While this has widely been celebrated by social justice circles and opposition parties as an ideological win, Teltumbde has ironically questioned the consensus by terming it a con (deceit) census!

The genesis of the book lies in an article Teltumbde wrote in a news magazine recently. The book, though, is a 220-page treatise on the issue, divided into 15 chapters. Teltumbde dips into history and traverses through the development of caste from Vedic to current times.

He is sceptical of the BJP’s sudden U-turn, and slams the ruling party’s track record in data management. Teltumbde questions the Modi government’s claim in 2015 that there were eight crore errors in the Socio-economic caste census (SECC) conducted by the previous UPA regime, by stating that the registrar general and census commissioner of India had claimed that 98.87% of the data on individual caste and religion was “error-free in SECC.”

Referring to the stampede at Maha Kumbh Mela earlier this year, the author says the government claimed 29 deaths, while a BBC report pegged it at 82. He feels the privileged among the ‘upper’ castes will hesitate to participate in the census (a recent instance is Narayana Murthy and Sudha Murty’s refusal to participate in the social and educational survey in Karnataka), leaving only the poorer ‘upper’ castes in the fray. Thus, he contends that the resultant data will be used to show that the ‘upper’ castes are also backward, and make a case to further establish the reservations for Economically Weaker Sections (EWS) and weaken caste-based reservation. This, he alleges, will be perfectly in sync with the ideology of Sangh Parivar. Known for his bold views and sharp arguments, Teltumbde reiterates that the caste system is rooted in socio-economic and societal relations, which cannot just be fought on ideological grounds. To buttress this, he explains that the Shramanic religions (Jainism and Buddhism), though ideologically opposed to Brahminism, couldn’t challenge it structurally. While conceding a demographic shift towards Islam in the medieval times — mainly from amongst oppressed communities — Teltumbde explains that the structural roots of caste remained the same.

Articulating the colonial census as a British ploy to understand Indian society and then control it through its ‘divide-and-rule’ policy, Teltumbde shows how the colonial regime rigidified caste, with each caste seeking to enumerate itself among those considered ‘upper’ castes. He feels the reservation scheme in post-colonial India has resulted in a different phenomenon of “competitive victimhood,” with each caste trying to claim backwardness for quota benefits.

By placing the “annihilation of caste” (as Dr BR Ambedkar put it) as the ultimate goal, the author says: “This is the core argument against the caste census that this book makes. If equality is the aim, a caste census can never deliver it. On the contrary, it risks unleashing caste turbulence, as history shows, which will outweigh potential gains many times.”

The principal demand after the caste census (assuming it’s accurate) will be a push for a higher reservation share (75% reservation has been Rahul Gandhi’s pitch). While it may be argued that this is logical and necessary, Teltumbde juxtaposes this push with neoliberal realities, arguing that the very base for reservation (government and public sector jobs) is being constantly eroded by the neoliberal setup.

Teltumbde’s style is lucid, his articulation effective, and his characteristic boldness admirable. His views enrich the debate over the caste census, which has thus far been limited to binaries. While tearing into the BJP’s hypocrisy, he questions the intent behind the sudden shift in the Congress’ stance, attributing it more to electoral considerations.

Just as in his pioneering work, Iconoclast: A Reflective Biography of Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar, Teltumbde uses his scholarship and insights to question set dictums of the progressive movement. His unflinching commitment to the annihilation of caste and fighting social inequities makes the book a tour de force and a much-needed addition to the burgeoning literature on the caste census. Teltumbde’s warnings have been welcomed by social justice adherents, but they have disagreed with his views that the caste census has more cons than pros. While the colonial intent behind the caste census might not have been all kosher, it’s also true that the census fuelled anti-caste movements and armed them with empirical evidence.

Critics argue that deliberations about the census in contemporary times have sensitised the public about systemic power asymmetry. Though the book is extensively researched and brilliantly argued, it could’ve been a tad shorter. That said, it is a must-read for its critical evaluation of the exercise.