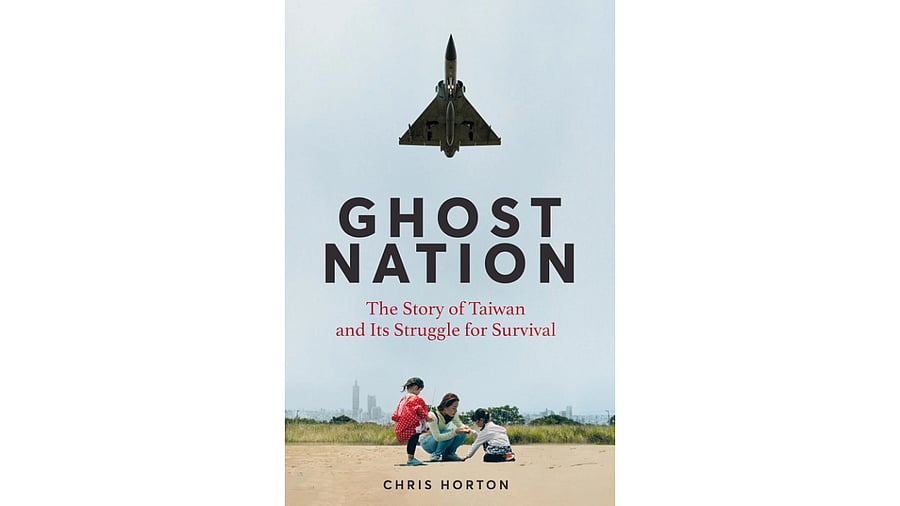

Ghost Nation

Ghost Nation by Chris Horton sets out to dismantle the persistent narrative that Taiwan is naturally and historically a part of China. The book takes direct aim at Beijing’s claim that Taiwan is merely a small island off the Chinese coast and a renegade province awaiting “reunification.”

Horton argues that Taiwan’s history did not begin with the Republic of China’s retreat to the island in 1949. Instead, he highlights a long-standing and distinct society, economy, political culture and historical trajectory that predate the ROC’s arrival.

As he puts it, “The story of Taiwan begins with its Indigenous people, who, as the island’s original stewards, are also living refutations of the CCP’s irredentist claims on the island country.” For Horton, the essential fact is that Taiwan was never fully governed by China; therefore, Beijing’s reunification rhetoric is not only weak but also expansionist.

Xi Jinping’s repeated insistence on reunification “at any cost” offers Taiwanese citizens a troubling preview of the future. Xi’s linking of the China Dream and the rejuvenation of the Chinese nation to the goal of unification further complicates the present political landscape. As Horton observes, “Whether from first-hand experience or through stories told by elder relatives, the Taiwanese see echoes of their recent dark past in Xi Jinping’s modern China.” This sense of déjà vu shapes how contemporary Taiwanese society interprets Beijing’s ambitions.

After nearly forty years of martial law, Taiwan’s transition to democratisation in 1996 fundamentally reshaped the island’s identity. The end of authoritarian rule encouraged a renewed engagement with Taiwan’s own history and the emergence of a distinctly Taiwanese consciousness. Today, Taiwan functions as a vibrant democracy with a free press and an active civil society. Yet echoes of older Chinese claims persist, particularly within the Kuomintang (KMT), which continues to favour maintaining the status quo. Horton argues that “The Chiangs’ unwillingness to abandon their China dream helped trap Taiwan in the diplomatic limbo which it inhabits to this day.” By contrast, the rise of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) has strengthened calls for greater autonomy and resistance to the 1992 Consensus, challenging long-standing geopolitical assumptions.

This political shift has been accompanied by increased Chinese aggression and sharper threats of military coercion. Xi Jinping has gone as far as calling Taiwan a “sacred territory,” heightening the sense of urgency. Against the backdrop of the Russia-Ukraine war, the stakes feel even higher. Horton notes that any attempted invasion of Taiwan “would be the largest attempted amphibious invasion in human history.” Though Taiwan is militarily smaller, “geography is very much on the side of the planners in Taipei,” offering natural defensive advantages. Still, Beijing’s narrative remains unchanged: “Taiwan is ours and Taiwanese people do not exist.” This messaging reflects a larger effort to erase Taiwanese identity entirely.

Horton also underscores how Taiwan has been repeatedly shaped and constrained by geopolitical forces. The United States has played an instrumental role in defining Taiwan’s trajectory, though its policy remains deliberately ambiguous. As Horton writes, “The US’s current-day Taiwan policy is a patchwork of very careful language spread across one federal law, three communiques with China and a once-classified set of six assurances to Taiwan made by President Ronald Reagan.” Yet, as China’s economic power has grown, more countries have chosen to align themselves with Beijing’s interpretation of the One-China policy.

Horton emphasises that “Taiwan’s international status has consistently been under attack as governments, corporations and individuals erase Taiwan’s sovereignty and its people to stay in Beijing’s good graces.” This erosion has led to a steady decline in the number of states maintaining formal diplomatic ties with Taipei. One of the book’s most striking insights emerges from a conversation with a Taiwanese diplomat, who asks, “If nobody recognises the ROC any more, does it just become Taiwan?” The question underscores Horton’s central argument: Taiwan and the ROC are not identical entities, and Taiwan’s history predates the ROC.

Horton’s approach to the “Taiwan question” is both nuanced and engaging. Drawing on interviews, personal experience and archival research, he layers individual stories with broader geopolitical developments to create a textured understanding of the island’s predicament.

The title Ghost Nation captures the central tension: Taiwan possesses all the attributes of nationhood — its own history, culture, politics and society — yet it is rendered spectral by international hesitation and Beijing’s insistence on rewriting its past. The world’s sudden recognition of Taiwan’s importance during the 2021 pandemic and the global chip supply chain breakdown only reinforce how much the international community depends on Taiwan’s continued sovereignty. As Horton argues, “For countries whose stability and prosperity depend on Taiwan’s continued sovereignty, it is vital for policymakers, journalists and voters to be able to differentiate between the truth and lies about Taiwan.” Understanding Taiwan on its own terms, rather than through Beijing’s framing, is essential.

Ghost Nation is not just timely; it is necessary. It adds depth to the existing literature on Taiwan and offers a clear, compelling account of the island’s struggle for recognition. The book provides a fresh lens through which to understand Taiwan’s plight and is essential reading for anyone seeking to grasp the real Taiwan — beyond its geopolitical label.