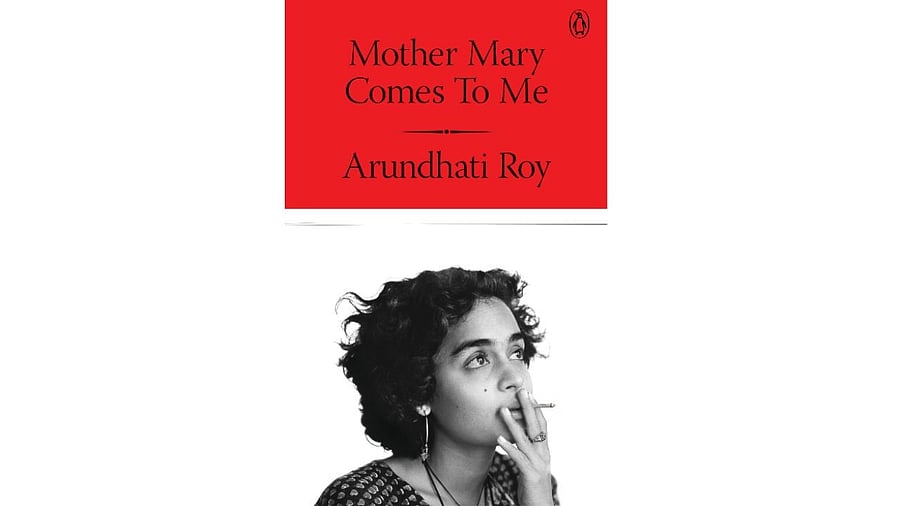

Mother Mary Comes To Me

Credit: Special Arrangement

John Berger, the British writer and cultural thinker, wrote to Arundhati Roy in response to her essays on the Narmada dams that her fiction and non-fiction walked her around the world like her two legs. Roy mentions this note in Mother Mary Comes To Me, her first memoir, and says Berger was one of the few people who didn’t see her works under the two groupings as in conflict with each other.

At another point in the book, she talks about the absurdity of being identified as a ‘writer-activist’. Is the writer, by definition, not engaged with people and what impacts their lives? Is that not among the determinants of her pursuit, as a teller of stories? So why the hyphenated apportioning of identity, “something like sofa-bed”?

Roy has had to respond to this perception of duality in her public, post-Booker life — the idea of two disparate halves melding uneasily into a whole, into writings that are searingly honest but are also marked for their cross-genre infusions.

The memoir is not where she seeks to defend, or even explain, her considerations as a writer, or her choices as a political being. Instead, she turns to her mother — the titular Mary, the mercurial Mrs Roy — and in trying to understand her rancour and rebellion, pieces together her own compelling origin story. Mrs Roy, an iconic educator whose petition in the Supreme Court led to a landmark judgement upholding equal inheritance rights for Christian women in Kerala, died in 2022.

This is where the daughter revisits the mother for what she was and what she has left behind.

Dark, underlying humour

The memoir has at its centre a child watching her legendary mother from her ignored, inconsequential corner.

For her daughter, Mrs Roy was both shelter and storm. Mother Mary builds on this fraught dynamic in a largely linear, interspersed arrangement of events that trace the journeys of the two women, with strong social commentary forming a busy, evolving backdrop.

Roy writes with sublime power. Her narratives draw on people in their everyday wars for homes and fair lives, and in a nation in transition, for identity and the freedom to be. The author writes in a language that is outside her. She must hunt it down like prey, “Disembowel it, eat it”.

This is a language that also shapes a dark, underlying humour and lends the narrator a transcendent rootedness, across timelines and topographies — by the Meenachil in Ayemenem, cycling to work on Delhi’s streets, standing with a lost, wronged people in strife-torn Kashmir.

What is this disquiet Roy senses in safe places, making them dangerous, prodding her to break away and run? Why would she drop work on a widely anticipated second novel to walk with the Naxalites in the forests of Bastar? How could she hold on in the face of relentless hostility — she the wild child with calloused feet and runaway at 16, the dodger of intrusive men in faraway cities, the outsider who risks sedition charges, criminal contempt, and a day in prison to speak for those who don’t have many on their side, the gaddar the Hindu Right loves to hate?

Mother Mary is where the author tries to rationalise her many worlds and a constant, debilitating fear, “a cold, furry moth on a frightened heart”. This is where she sees why things are the way they are; why she is – “...because I’m my mother’s daughter. Because I could not do otherwise.”

Poignant and reflective

The author has a problem with inherited houses: they own the people who live in them. The intensity of familial bonds unsettles her; the structural compulsions of love make her step back and reassess.

Mother Mary has portions where Roy writes like a fan in the stands, about her mother’s militant courage and radical kindness.

This tenderness, this resilience for rejection and refusal to stop loving, despite having suffered years of humiliation and cold rage, may have come from an entrenched emotional distance — the adoring daughter, never enough for her superstar mother. The author writes that she left her mother because staying would have made loving her impossible. However, this is Roy Senior’s story too.

Mother Mary is a hard book to write, Roy notes initially, but she must. She must make sense of a love denied, of the thorns her mother set down for her, “like little floaters in my bloodstream”. The recall, however, seems to come from a place of relative peace, excised from the bitterness and complexities of their relationship.

Poignant and reflective, Mother Mary is a rare personal account that blends well into the political. Early in the book, Roy narrates a moment of loss in relation to the subject of her deep grief; it’s a response that surprises her.

The question she asks is revelatory: What makes people revere their persecutors, even grateful for their oppression?

The light Mrs Roy gave her students eluded her daughter and son, LKC. For them to shine, the children had to “absorb her darkness”. But this is a darkness the author is grateful for — “It turned out to be a route to freedom, too.”