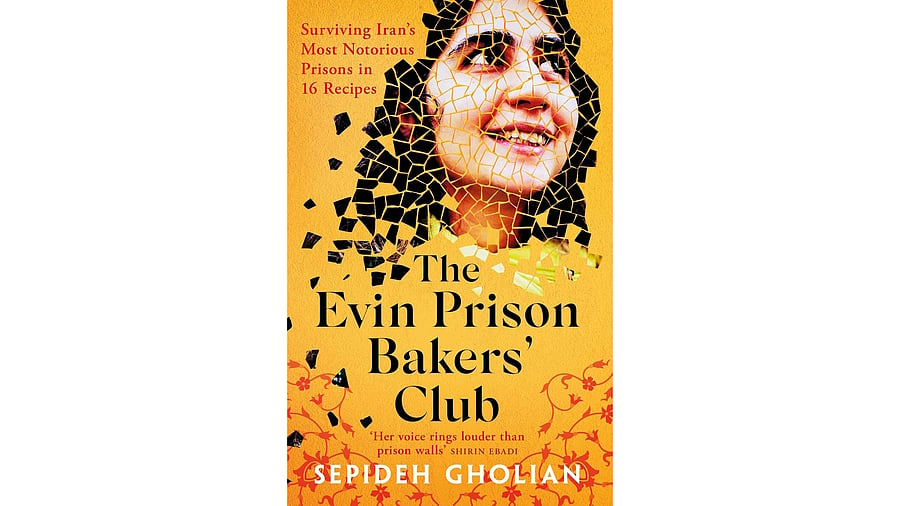

The Evin Prison Bakers' Club

Have you ever come across a prison memoir that is also a recipe book? The Evin Prison Bakers’ Club, written by Sepideh Gholian, is a genre-bending work of non-fiction that seeks to inform and educate as well as bear witness. It consists of 12 chapters written in Persian, translated by Hessam Ashrafi into English.

The author is an Iranian journalist, activist, and human rights defender focused on labour rights. She was arrested in 2018 for organising support for a workers’ strike, and she underwent brutal torture in detention. Her spirit remained unbroken despite the hardships she was compelled to endure. She has spoken out about being sexually harassed. In 2023, she appeared in a video where she removed her hijab and called for the downfall of Ali Khamenei, the Supreme Leader of Iran. In 2024, she went on a hunger strike. At the time of writing this book in August 2024, she was back at Evin Prison. She was released in June 2025. At first, it seems ironic that a woman who chose hunger as a mode of protest wrote a book about food. As one dives deeper into the book, it becomes increasingly evident that food symbolises acts of nurture and care between imprisoned women who build a sisterhood. “Baking allowed me to forget about the beatings I received for being a woman,” writes Gholian. Her sense of humour seems to help her survive in the harsh circumstances. She adds, “I am not a good baker…I’m not a baker at all…I do it without being skilled at it.”

The writing style, as evident here, is conversational. The author speaks directly to the reader, almost like exchanging light banter with a friend, anticipating questions that might pop up, and responding to them pre-emptively. “You might well ask, Isn’t prison…prison? How the hell could you be making confectionery there? And you would be correct,” she writes.

One learns that she used her privilege as a political prisoner to set up a kitchen. The process of baking for other imprisoned women allowed her to have “a few decent days” amid all the oppression and violence that she faced. Not one to lose an opportunity for a good laugh at the expense of her captors, she writes, “They were plainly not going to release us so we were going to get a tart tin out of them, at least.” Through these words, the author shows that resistance can be funny and sassy in addition to being resolute, angry and fierce.

This book contains recipes for tres leches cake, finger-twist halva, Kachi pudding, pumpkin pie, gosh-e fil, scones, lemon meringue pie, Dutch cheesecake, gheliyeh, date crumble, saffron cookies, apple pie, madeleines, Swiss roll, and doughnuts with crème patissière. Each preparation is made with love. Apart from the ingredients, portions and cooking instructions, the author shares stories of the prisoners who happen to be not only her friends but also comrades and sisters bound together in their dream for a democratic Iran where freedom, justice and human rights are available to every person.

The author writes about Sepideh Kashani, Niloufar Bayani, Mahin Boland Karami, Somayeh Shahbazi Jahrouii, Makieh Neisi, Sakineh Sagoori, Nazanin Zaghari-Radcliffe, Elaheh Darvishi, Zahra Hosseini, Maryam Haji-Hosseini, Fatima Muthanna, Zahra Zehtabchi, Maryam Akbari Monfared, Monireh Arabshahi, Yasaman Aryani, Marzieh Amiri, and Mahboubeh Rezaei—all imprisoned women punished for challenging the status quo.

She offers disturbing glimpses of prison life. One reads about a woman with “a scorched chest” whose brother-in-law poured boiling water on her. Another woman kills a man who wanted to rape her sister. Later in the book, one encounters a graphic description of an unmarried pregnant woman who starts haemorrhaging after “a DIY abortion” in prison. One also meets a woman whose job is to clean the toilet and wash the prison guards’ underwear. It is astounding to witness the author’s vision for what a book can do. She intersperses her diary entries and recipes with letters, footnotes, and references to poems and protest songs. She holds forth about forced disappearances, mass graves, honour killing, and persecution of ethnic minorities who are Sunni Muslims. Her courage shines through on every page.

Also worth reading is the introduction written by Maziar Bahari. He is a journalist and documentary filmmaker who founded IranWire.com, where the Persian version of this book was published. He reveals how the book was put together, while withholding specific details “for security reasons”. He had to coordinate with several people, including the author, to “receive separate chapters by text or photos showing scraps of paper”. These fragments were then typed up and edited.

Reading this part of the book gives one goosebumps because it salutes the commitment of publishing professionals who went to great lengths to bring this story to light.