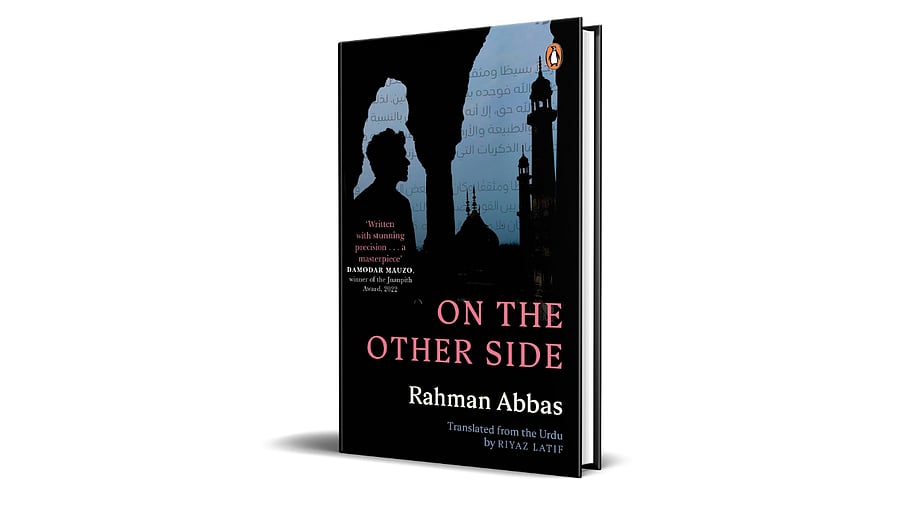

On The Other Side.

When an individual dreams of becoming an author, the dream largely comprises bestselling books, admiring readers, and perhaps, remittances in bank accounts. Nothing in that dream prepares them for being dragged away from home by policemen like a criminal and spending time in prison wondering what their crime was. Yet, many an author in the history of human civilisation has undergone this trial, for training their lens on an aspect of society that those in power would rather have shoved under the carpet.

Mumbai-based Urdu writer Rahman Abbas lived that experience upon the publication of his first novel, Nakhlistan Ki Talash (Search for an Oasis) in 2004. He was booked under Section 292 of IPC on charges of obscenity, was put in Arthur Road Jail, and in quick succession, was fired as a lecturer in a junior college in Mumbai.

It took more than 10 years for redemption, which came on 19 August 2016, when a Mumbai court ruled that the charges against Abbas were unwarranted. During that period he won the Maharashtra State Urdu Sahitya Akademi Award for his third novel, Khuda Ke Saye Mein Aankh Micholi, in 2011. This novel was recently released in English as The Other Side.

It was with this background in mind I approached The Other Side, hoping to get an insight into the effects the trial must have left on Abbas’s writing, considering that it was originally published while he was still mired in a legal tangle. Right in the beginning, on page 3, I found what I was looking for and hoping for — the author had been undeterred and unrelenting in exposing the shady layers of society that people collectively ignore to erect a facade of morality.

He writes: ‘Unexpectedly, he [Abdus-Salam, the protagonist] remembered the Imam Sahib of his childhood days who frequently detained his friend Nazeer Umar Sheikh after madrasa to have him massage his feet… For several years, the sharp whiff of betel leaf, laced with ‘120 tobacco’, a brand that Imam Sahib consumed, seemed to waft from Nazeer’s body… The crux of the matter is that Nazeer could not continue his studies beyond the introductory primer for the Quran. And then, God knows what possessed him that, stuffing his clothes into a sack, he stepped out of his house and disappeared into the labyrinth of Mumbai No. 8, where the largest flesh-trade bazaar in this tyranny-ridden city has flourished for ages,…’

It’s anybody’s guess what an ‘exposé’ of this kind is likely to have on the guardians of any religion. “But as a writer, I cannot do otherwise,” says Abbas. “What is a writer’s role in society? When you read serious literature, throughout the world its role has been to present the crude realities of society. The writers love society as much as others, and they write the truth in the hope that society will do something about it. Of course, writers have had to pay the price for that. But I believe in what [Irish novelist and poet] James Joyce said: ‘A writer is the conscience of a country’, and therefore, I did not stop writing,” adds Abbas, not as an apology or an explanation but as a matter of fact.

The Other Side is the story of Abdus-Salam Kalshekar, whose ambition was to complete his seven-volume Dastan-e-Ishq (Saga of Passion) — the stories of his past amours — before his death. He manages to publish only three and so an author sets out to write a novel about the remainder of his love stories, after scanning his diaries and meeting up his friends and acquaintances. In the course of getting to know the protagonist, the author unravels the deep secrets of the world he was a part of, such as the sexual abuse of children as stated in Nazeer’s story above, and the trembling vulnerability of a same-sex relationship that Abdus-Salam discovers in his extended family in his youth.

The sensitivity with which Abbas deals with topics that can become incendiary in the hands of extremists, is, perhaps the biggest reason his books have continued to win awards, despite their incriminating candour. His fourth novel, Rohzin, too won the Maharashtra State Urdu Sahitya Akademi Award, in 2017; it went on to win the national Sahitya Akademi Award in 2018 and was longlisted for India’s richest literary award, the JCB Prize for Literature, in 2022. Abbas is the author of 10 books, including six novels, some of which have been translated into French and German as well.

While Abbas has moved on from his brush with extremism nearly two decades ago, he hopes that Section 292 of IPC, “that is more often used to harass a creative individual than to prevent obscenity”, will be abolished one day. “It’s a colonial-era law imposed by the British who came to India with a very foreign sense of morality. We are the land of the Kama Sutra, Khajuraho and the Mahabharat, where Krishna takes the form of Mohini [the female avatar worshipped among the transgender community in several parts of India],” he says. He also hopes that even though a major part of the world is turning “right-wing”, tolerance will eventually prevail, and most importantly, Urdu will be rescued from the clutches of religion to become a progressive language as it was until the 1970s.