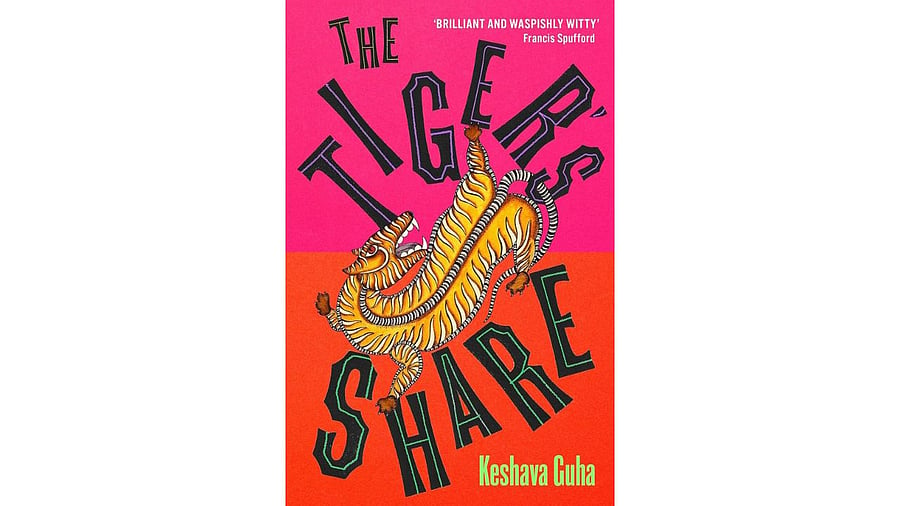

The Tiger’s Share.

Wills, inheritance and successors are words heard in passing, mostly as vague issues that concern others. Yet families are uprooted, brother turns against brother and enemies are made for the afterlife too, just based on how a property is carved up at the death of the patriarch. This is the most devastating reality that most face, even more grim and menacing than the death of a parent. Yet most flinch from taking it head-on in conversations or in writing. It is so distasteful or traumatic, ‘let’s not go there,’ is the reigning sentiment. Kudos to Keshava Guha, author of The Tiger’s Share, for showing in minute detail the ruthlessness of siblings when they imagine their inheritance is at stake. Another surprising bit is how flawlessly sibling dynamics have been captured, especially when one excels at life, and the other is petty.

This is essentially a Delhi book, where the city’s various influences actually propel the movement of the storyline. The Delhi ethos, the antecedents of Delhi businessmen, Sundernagar, The Book Shop at Khan Market, the typical Delhiite, its unique summer and the air quality — each find mention here, and for sure, this tale would not sit as well in any other place under the sun. “October. Season of smogs and mellow murderousness. A month in Delhi, that begins in summer and ends reliably in smoke…. When it arrives in Delhi, it has a mutually stimulating encounter with our own producers of particulate matter: vehicles, factories, coal power plants, and construction dust. There was a day in October when you knew it had arrived. You smelled it late morning like the news of your neighbour’s lunch.” All descriptions are done accurately, almost lovingly. In talking about a brother’s girth and buffalo cheeks, there is an element of truth as well as the desire to pin down what is an epidemic among the people here.

Though as much, this book is about sisterhood: the affinities that women develop with one another under uncertain circumstances. It documents the utter estrangement of a woman in the world of patriarchy. She is not right for her sibling, cosseted as he is by the certainty that the world is his for the taking. Her mother dismisses her for not being a homebody like herself, disapproves of her finding a footing in the world. In some cases, her father loves her, but with an intellectual quality best expressed through silence. The only recourse is another woman who shares her experience, who can reach out with true empathy for her world is much the same.

Here, Tara and Lila find each other partly by circumstance and partly as their situations are parallel, such that they make sense only to the other. “Well, if we each get our own version of Paradise, maybe he isn’t here, but he’s at an even better chautha.” They gravitate towards each other, for they are kindred spirits; they understand each other perfectly. “And they’d rather let the house rot empty, a house worth dozens of crores, than come to a reasonable settlement. …Thank God we’re not that kind of family, and I will never let us become that kind of family.”

Despite it all, Brahm Saxena, the father, is the actual protagonist of this book. He is made of hero material, the reason why fiction is preferred over fact. A self-made man who retired at 65, retreats into further silence, his daily routine and the newfound love for scriptures. These scriptures are used not to cosy up to an imagined godhead but to sieve out what meaning he could give to his own life. A forerunner to that is the summit, where he calls for a family conclave to tell his two children that he would give away all the money he has made. While Tara is committed to protecting her father’s vision, her brother considers deeming him insane, while his wife tells him it is all bakwaas. He wishes to make positive changes to this world, and in an act that could be called gruesome by many and altruistic by others, he ends his life in a unique way.

This is a book crafted to perfection, honed till the words shine. The language is so beguilingly simple, large tracts may be read without effort. It is almost addictive, the vision of Delhi, real or imagined, that he conjures up in mere words. Though parts of the book are a bit too dialogue heavy, where it is not, lightness of touch, wit and that sheer aha moment characterise interactions between the characters. Most notable is the voice here, which is androgynous. Which is lovely. It takes on a woman’s fight and her inner world, and ably matches it with analytical thinking, brutally sparse thoughts and even the swagger that men have. This is a serious writer leaving his stamp on India’s literary scene.