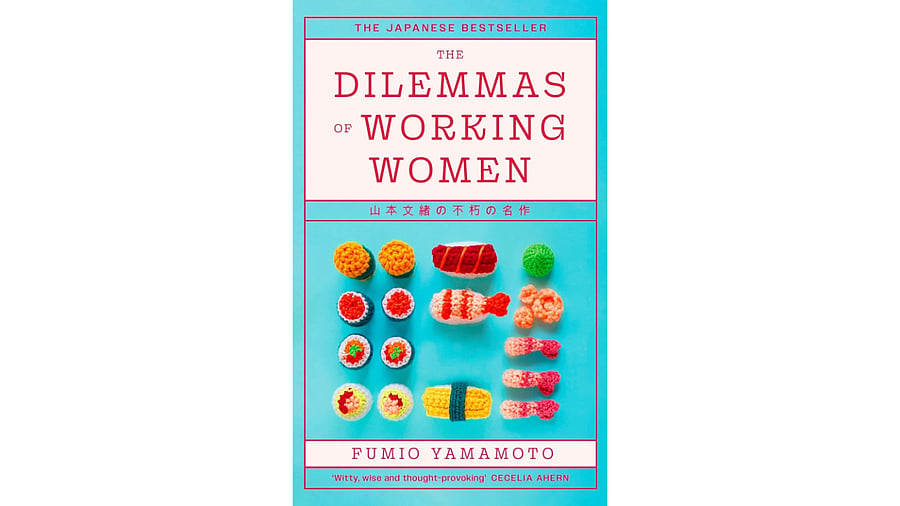

The Dilemmas of Working Women

At the turn of the millennium, Japan was undergoing quiet but seismic shifts. The economic bubble had burst, corporate restructuring had begun to reshape middle-class aspirations, and women, often educated, ambitious, and overburdened, found themselves suspended between old patriarchal expectations and new capitalist demands. It is against this backdrop that the late Fumio Yamamoto (1962–2021) published The Dilemmas of Working Women in 2000, a collection of five short stories that captured, with searing honesty, the emotional and moral turbulence of contemporary urban life.

Now translated into English brilliantly by Brian Bergstrom, Yamamoto’s collection feels startlingly relevant even two decades later. Each story follows characters, mostly women, but occasionally men, who find themselves trapped in the contradictions of modernity: between work and leisure, desire and duty, autonomy and belonging. Through first-person narration, Yamamoto creates an intimate, sometimes uncomfortable proximity to her characters’ inner worlds. Her tone is witty yet dark, tender yet unsparing, as she lays bare their loneliness, alienation, and longing for connection. Money, love, illness, and gendered expectations thread through these stories, revealing how economic life becomes inseparable from emotional life. In Yamamoto’s hands, the dilemmas of work are never merely professional; they are existential, echoing through the body, the home, and the heart.

Yamamoto’s fiction emerges from a distinctly feminist consciousness, though it never outrightly declares itself as such.

Her critique unfolds through the mundane rhythms of everyday life — the tired commute, the hollow small talk at work, the quiet ache of solitude after a long day. Post-bubble Japan was marked by economic uncertainty and the slow unravelling of the corporate dream, yet the social expectation that women maintain composure, beauty, and care remained intact. Yamamoto writes from within that contradiction. Her women are neither heroic rebels nor passive victims; they navigate a landscape where empowerment is both promised and denied. In doing so, The Dilemmas of Working Women becomes a subtle commentary on the gendered violence of neoliberal modernity, where freedom is conditional, and choice is often an illusion.

Beneath the performative politeness of office corridors and the allusive perfection of domestic order lies a deep exhaustion, one that Yamamoto captures with humour, melancholy, and a piercing sense of truth.

The story that lingered with me the longest is “Here, Which Is Nowhere,” perhaps the most nuanced and haunting in the collection. Its protagonist, Maho, is a woman suspended in the thick fog of care work, tethered to the needs of everyone around her. For 21 years, she has tended to her husband, then her hospitalised father-in-law, her widowed and embittered mother, and her almost-grown children who treat her with contempt. Her husband’s salary has been halved, forcing her into a part-time job that only deepens her exhaustion. The domestic space that should have offered rest becomes instead a site of endless service. Yamamoto renders Maho’s world with such unflinching intimacy that the reader can almost feel the heaviness of her body, the dull ache of repetition, the silence between chores.

The emotional crescendo arrives when Maho’s simmering rage erupts: she punches her son during an argument, only to be gutted by her daughter’s words, “I don’t ever want to become like you, Mum! I need to start working as soon as I can so I can be free of this place. I can’t stand seeing the way you live!” It is a moment both devastating and familiar, where maternal love and resentment collide, and the generational cycle of female servitude exposes itself. Maho’s longing for one night of undisturbed sleep, for a small moment of solitude, becomes emblematic of so many women’s quiet, unfulfilled desires. Even when she finally allows herself a brief release, it changes little in the rhythm of her days. Yamamoto does not offer redemption; instead, she gives us the raw, unadorned truth of women’s weariness, the emotional labour that keeps families and nations functioning while draining the very lives that sustain them.

What makes The Dilemmas of Working Women so piercing is how easily its stories transcend the borders of Japan. The women in Yamamoto’s world could just as well be found in Delhi’s industrial belts, in cramped apartments in Dhaka, or in the open-plan offices of London and New York. Their struggles of endless emotional, mental, and physical labour are eerily familiar. Yamamoto writes them with compassion, revealing how such constant giving erodes the self slowly, imperceptibly. In their quiet fatigue, we glimpse a collective truth: that the world runs on women’s endurance, even as it refuses to make room for their dreams.