We are all conspiracy theorists at heart. As a character explains, “There was no free-floating globe because the earth was controlled by reptilians living underground, whose tunnels can be accessed only through a secret entrance on an ancient ice sheet on the ‘forbidden continent,’ and all the politicians — including every American president since Kennedy—have privately visited Antarctica to make deals with these lizards. They feed on our suffering, ya know? We’re nothing but a crop to them.”

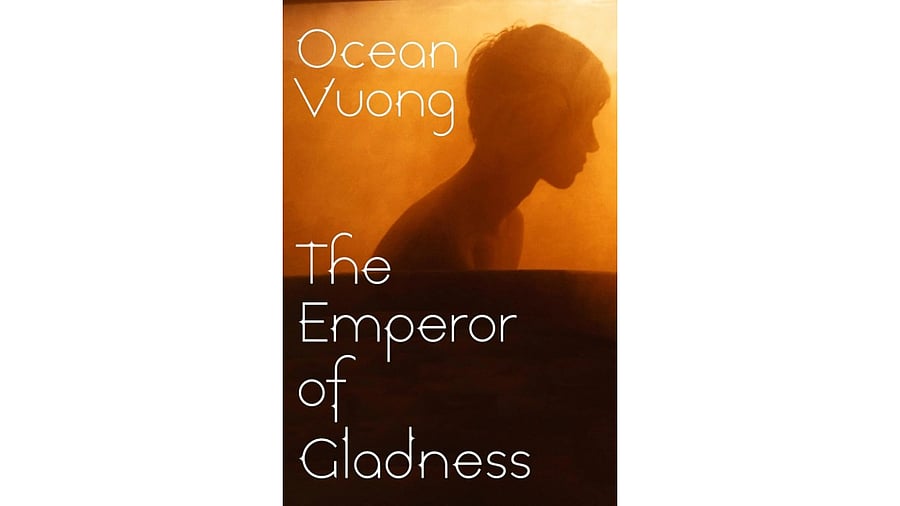

Ocean Vuong’s second book of prose, The Emperor of Gladness, is a story of fractured and reconstructed families, of the circular dance between mothers and sons, of the directionality of directionlessness, of the constellations found in the simplest of lives built from leftovers. It’s a story of the invisible, the marginalised, the perpetually unseen, the working class. It’s a story of “people (who) vanish all the time and leave no trace, even here in America.” Especially here in America. Through his words, obscurity itself finds a texture, a shape.

It’s the story of Hai, who, at the beginning of the story, finds himself at the edge of a river, contemplating its dark invitation. As we find him, so does Grazina, a Lithuanian refugee from World War II. War afflicts Hai’s past, too, whose family migrated from a war-stricken Vietnam. These two characters, both haunted by their pasts, both escaping from it, find a makeshift family in her dilapidated house with its cramped domesticity.

Here, in this museum of survival, two wars separated by decades find their common language in the art of enduring. Forgetting becomes their shared language. For Grazina, it’s involuntary: age stealing her memories like a thief in the night. For Hai, it’s survival: deliberately burying what threatens to drown him. In their conversations, they build bridges from incomplete thoughts, each supplying what the other cannot remember or chooses not to recall.

But the mathematics of family multiplies in unexpected places. At HomeMarket, a fast-food chain, he joins an eccentric cast of characters, each suffering, each persevering, yet dreaming all the same, “weatherworn and perennially exhausted or pissed off or both.” BJ, the store manager, dreams of becoming a professional wrestler. Sony, both Hai’s cousin and a Civil War obsessive, dreams of liberating his incarcerated mother and reconnecting with his distant father. Russia, whose Tajikistani roots belie his name, works multiple shifts — FedEx warehouse and an occasional slaughterhouse — to fund his sister’s rehabilitation. Despite regular racist abuses from customers, Wayne refuses to stop roasting meat to maintain his pitmaster family’s legacy alive.

Each carries their own conspiracy theory about escape, their own mythology of elsewhere. The dreams sustain them. The work destroys them.

And it is so that HomeMarket becomes a theatre where the farce of the American Dream is reheated nightly under buzzing lights. Through burn scars, aching wrists, greasy skin, powdered cheese under the nails, aching jaws from fake smiles, that dream dissolves into the reality of bodies breaking, day by day, shift by shift.

In the end, Emperor of Gladness maps the topography of the unseen. Vuong excavates both the hidden worlds within us and the hidden worlds that surround us — the elaborate deceptions we construct for daily survival, the ghosts that colonise our thoughts, “your head a coffin to keep memories of the dead alive.” His subjects are the countless living on the outskirts of society — the addicts, the waiters, the elderly, the drivers, the makeup artists — the shadow workforce, the deliberately invisible, their invisibility manufactured through exclusionary policies and subsistence wages that sustain the myth of progress. The story insists that this universe of the unrecorded and unremarked is still a universe, validated by its very own interiority, its very consciousness a form of presence.

Vuong, in his characteristic medley of prose and verse, of swaying, branching, looping sentences that hold emotion like a lung holds air, of optimistic, melancholic descriptions, thus creates a world of the invisible. His form wanders, stumbles, returns, interrupts, repeats itself, the syntax mirroring his characters’ uncertainty.

This uncertainty can be seen in the details. A man names his son after his favourite chess piece. A character chases a diamond trapped in his deceased father’s palm.

We are all conspiracy theorists at heart. Not from delusion, but from necessity — the human hunger to find purpose in purposelessness, hope in hopelessness, direction in directionlessness, love in lovelessness. The Emperor of Gladness is, then, a conspiracy theory about conspiracy theories.