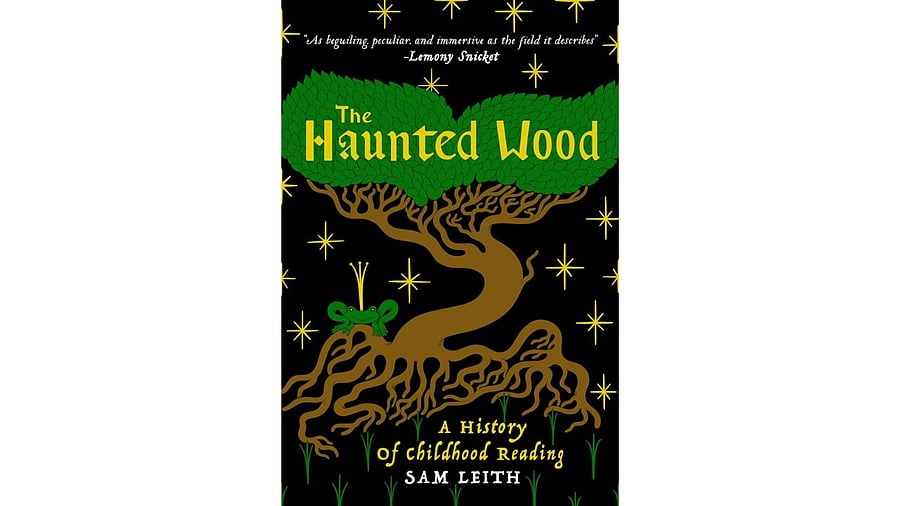

The Haunting Wood.

Sam Leith, a literary critic and podcaster based in England, sets himself a mammoth task in his intellectually stimulating volume titled The Haunted Wood: A History of Childhood Reading.

“I have set out to trace the history of children’s stories from their prehistory in the deep past of the oral tradition to, roughly, the turn of the millennium,” he states, capturing succinctly the vast historical sweep of a genre that is often patronised, underestimated or sentimentalised.

Leith demonstrates that writing history is an art form. Rather than merely documenting a set of events in chronological order, he narrates with wit and verve, lending emotional resonance. His analytical framework is interdisciplinary, informed by the work of scholars like Vladimir Propp, Joseph Campbell, Philippe Ariès, Lawrence Stone, and John Locke. Insights from folklore, comparative mythology, history, psychology and philosophy blend in with remarkable ease.

He writes with confidence and authority, animated by a passion that can be traced back to his own childhood. His father, an actor, read Rudyard Kipling’s Just So Stories aloud to him, relishing the cadences and modulating his voice for dramatic effect. The joy of that formative experience has clearly stayed with him and shaped his professional trajectory as a critic.

One of the book’s most persuasive claims is its insistence on treating children’s literature as foundational. He writes, “Children’s literature isn’t a defective or frivolous sidebar to the grown-up sort. It’s the platform on which everything else is built.” This is not mere ideological posturing but a conviction born of personal experience. Initiated into reading by his father, Leith has passed that inheritance on to his daughter. He adds, “It’s through what we read as children that we imbibe our first understanding of what it is to inhabit a fictional world, how words and sentences carry a style and tone of voice, how a narrator can reveal or occlude the minds of others, and how we learn to anticipate with excitement or dread what’s round the corner.”

These words ought to be prescribed reading for literature festival organisers who give second-class treatment to authors of children’s books by hosting them in shady hotels, scheduling their sessions at inconvenient venues, or not stocking their books in large quantities.

Leith also explores an intriguing paradox by venturing into the biographical worlds of authors who create safety and comfort for children despite traumatic childhoods of their own. Helen Lyndon Goff, better known as P L Travers of Mary Poppins fame, grew up with an alcoholic father. AS Leith recounts, “She coped with loneliness by pretending to be a chicken. She sat for hours, her arms clasped tightly around her body.” Her success in conjuring up a magical world, perhaps forged in adversity, speaks volumes about her resilience and her creative abilities.

Similarly, C S Lewis, who wrote The Chronicles of Narnia series, was sent off to boarding school after his mother died when he was only nine years old. In that restrictive environment, his imagination not only sustained him but also honed his skills as a fantasy writer. Such details from the personal lives of authors show how empowering the creative process can be for writers, who then provide catharsis and ignite hope in their readers.

What is most striking about this book is the curious stance that it adopts towards the construct of children’s literature itself, instead of taking it for granted. The author points out, for instance, that it was only in the early 20th century that “children’s publishing really became a distinct sector of the industry”. Before that, little distinction was made between adult and child readers. The change took place partly because of industrialisation, migration and new family structures.

“For most of British history,” Leith notes, “middle-class children were both the protagonists and the audience for children’s stories,” and their experience of childhood was often mediated by nannies, governesses, nurses or ayahs. While the book has a predominantly British focus, it invites productive comparisons with India. Even today, children’s books in English published in India cater mostly to affluent families, with protagonists and plots reflecting their concerns.

Leith traces how the readership for children’s literature in England has gradually expanded across racial and class lines, leading to demands for more and better representation. Malorie Blackman’s books, for example, attempt to counter the erasure of Black people in British children’s literature. She started out by wanting to write books that she would have loved to read as a child. A comparable development in India would be the Different Tales project undertaken by the Anveshi Research Centre for Women’s Studies to tell stories of Dalit, Muslim and Adivasi characters who have been conspicuous by their near absence from Indian children’s literature.

The Haunted Wood is highly recommended. It is a reminder that children’s literature deserves to be taken seriously because it shapes not only early reading habits but also the citizens of the future.