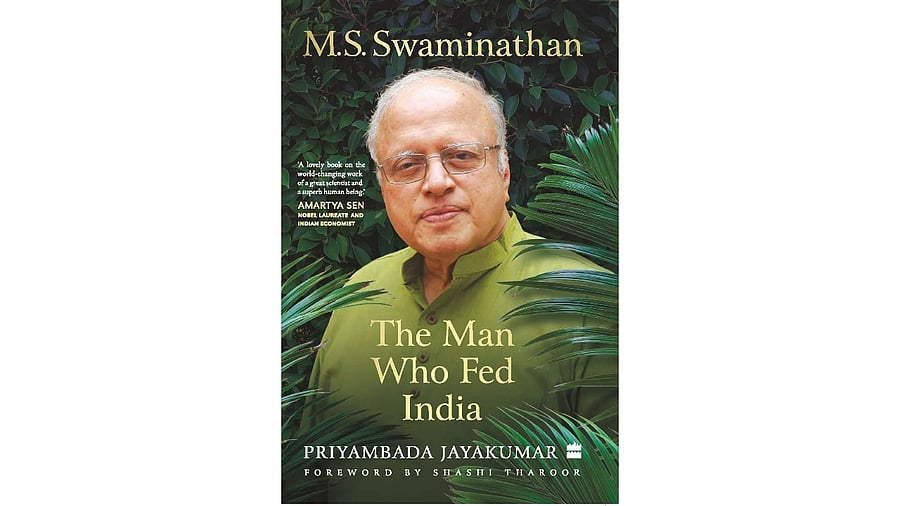

The Man Who Fed India

If the economist Amartya Sen showed that democracies avert famines but can live with chronic hunger, it was the plant geneticist M S Swaminathan who found a scientific and practical solution to that hunger. Both thinkers were influenced in their youth by the devastating moral catastrophe of the Bengal Famine of 1943 that claimed millions of lives.

“To those who are hungry, God can only appear in the form of bread,” said Mahatma Gandhi at Noakhali. Swaminathan made it his life’s mission to ensure that no one, anywhere, would go hungry.

Priyambada Jayakumar’s biography appears in the centenary year of the agricultural scientist. When parts of the world again face drought, desertification, geopolitical food insecurity, and agrarian distress, Swaminathan’s work speaks powerfully to the need for science and policy to work with ethical purpose to protect the most vulnerable.

Born in 1925, Swaminathan had been expected to study medicine like his father. His Gandhian convictions and his desire to serve the disadvantaged motivated him to study agricultural science, a field that could save millions from the indignity of hunger and starvation. After research in Holland, Cambridge, and the United States, he rejected offers of a tenured faculty position and a lucrative corporate job designing a superior potato chip. He returned to India.

Jawaharlal Nehru had declared, “Everything else can wait, but not agriculture” — even urging Indians to blend sweet potatoes with scarce wheat in rotis. Lal Bahadur Shastri issued the call “Jai Jawan, Jai Kisan,” urging Indians to give up one meal weekly to help the nation at a time of crisis. Farm productivity was central not only to the economy but also to resolving the urgent problem of food insecurity itself.

Early attempts to improve yields came up repeatedly against a challenge: as grains grew heavier, the slender stalks broke under their own weight. The search began for shorter, sturdier, “dwarf” varieties. A visiting Japanese scientist told Swaminathan about a promising new hybrid variety in the United States. When the Indian researcher reached out, the American scientist suggested that Norman Borlaug’s dwarf varieties developed in Mexico might be better suited to Indian conditions. Swaminathan had already met Borlaug during his postdoctoral research in the United States. They reconnected; after a prolonged bureaucratic delay, Borlaug was invited to visit India. History followed.

Defying the dire Malthusian predictions of Paul Ehrlich and William and Paul Paddock, Swaminathan introduced Borlaug’s high-yielding Mexican dwarf varieties of wheat to Indian soil. It was not a straightforward task. It took months of persuasion to convince the first farmer, a smallholder in Jaunti, to agree to try out the new seeds. What convinced him was Swaminathan’s personal investment in the project: for months, he had been spending his Sundays and public holidays in the farmers’ fields. The scientist’s sincerity earned the farmers’ trust.

At a time when the nation’s foreign exchange reserves were critically low, India imported 18,000 tonnes of seeds from Mexico at a substantial cost of Rs 5 crore. It was the largest seed shipment in history.

What followed the sowing of the seeds was revolutionary. The harvest was beyond bountiful. Schools were closed early for the summer so that grain could be stored in empty classrooms. Cinemas and train wagons overflowed.

Crop yields surged, feeding the nation and lifting countless small-holder farmers out of poverty. At a period when foodgrains were used as an instrument of foreign policy, India was finally free of humiliating “ship-to-mouth” dependency on American Public Law (PL) 480 shipments. Swaminathan had ensured a peaceful Green Revolution in India.

C Subramanian was Minister for Food and Agriculture; B Sivaraman was Agriculture Secretary. Prime Ministers Lal Bahadur Shastri and Indira Gandhi supported the bold vision of food security for the nation. This extraordinary outcome took place at the intersection of sound science, courageous policy, and the intrepid determination of farmers. Hunger would never again define India’s destiny.

The Green Revolution was the beginning of a new era in agriculture. As Director General of the International Rice Research Institute, Swaminathan continued to help nations achieve food security, with dramatic results. Large swathes of Asia began to heal from painful histories of colonial exploitation, conflict, and genocide.

When the Green Revolution later revealed ecological and regional imbalances, Swaminathan himself was among the first to recognise these limits, prompting his advocacy for ecologically responsible, equitable, and sustainable practices for an ‘Evergreen Revolution.’

In Jayakumar’s retelling of Swaminathan’s life, these acts emerge not as isolated examples of genius, but as expressions of a consistent moral vision: a commitment to academic excellence, nation-building, and public policy; science as a collaborative process, based on building bridges across the world, with non-hierarchical lab-to-land and land-to-lab interactions; and a steadfast conviction that science must promote peace, equity, and sustainability. Through leadership at multiple international organisations, he embodied a belief that the world is one.

Swaminathan won innumerable awards, including the Ramon Magsaysay Award and the first World Food Prize. In keeping with the Gandhian concept of trusteeship, he donated the award money to causes such as the education of migrant children and setting up a participatory research foundation.

Swaminathan saw small and marginal holders not as passive recipients of innovation, but as co-creators of knowledge. He recognised and valued their practical skills, dignity, and aspirations. As Chair of the National Commission on Farmers, he argued for farmers’ welfare not only as an economic imperative but also as a moral one.

Swaminathan was a lifelong follower of Gandhi. As a young university student, he had walked silently in the Mahatma’s funeral procession on the streets of Delhi, with countless other mourners. Those quiet moments were a prelude to a life devoted to service rather than self — and a belief that a nation’s dignity begins with the certainty that its people can eat.

The reviewer is the Development Commissioner, Government of Karnataka.