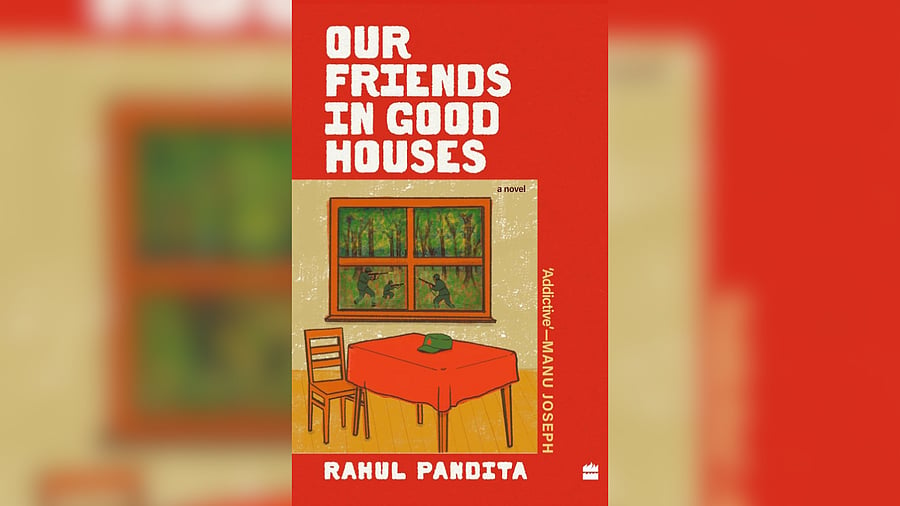

Our Friends In Good Houses

Rahul Pandita is a writer and journalist known for saying it as it is. His works often explore displacement and the dynamics of political power. From Our Moon Has Blood Clots to his recent novel, Our Friends in Good Houses, he has, in his writing, resisted both nostalgia and moral shortcuts. In an interview with DHoS, Pandita speaks about stepping away from lived memory to let fiction breathe, about the cost of speaking openly on national politics, and about finding peace in running. Excerpts

Your novel asked for two big detachments — pulling the protagonist away from yourself and fiction away from lived memory. What was that process like? And did that distance change anything in your sense of yourself as a writer?

Detaching myself from the protagonist and from the gravitational pull of lived memory was difficult, but necessary. I had to let Neel breathe on his own terms, even when some of his wounds overlapped with mine. That distance allowed the novel to find its own emotional truth rather than merely echoing my biography.

And yes, the process shifted something in me. Writing fiction demands a deeper surrender; it forces you to confront what you think you have already processed. In that sense, the novel became a quiet form of self-discovery.

Your choice of third-person narration is intriguing. Were you ever tempted to tell the story another way?

I did experiment briefly with a first-person voice, but it felt too confining for the kind of emotional and political landscape the novel needed to traverse. The third-person vantage allowed me to step back, to hold Neel with a certain tenderness while also observing him with clarity.

A sense of groundlessness and the search for an elusive home run through the book. What is “home” for you?

For me, “home” has never been a fixed geography; it’s a longing shaped by exile and memory. “Ungrund” comes closest to describing that condition; it is an inner groundlessness that you learn to live with. Over the years, I’ve realised that home is not a place I can return to, but a fragile state I build in moments of silence, in relationships that endure, and in the stories I tell.

The novel echoes themes you’ve explored in your essays. Did writing Neel change how you see your own memories?

Writing Neel didn’t change my memories, but it did change my relationship with them. Fiction lets you hold memory at an angle. It lets you see its cracks, its omissions, its stubborn brightness. In giving Neel his past, I was forced to re-examine my own, not to rewrite it but to understand its contours with a little more compassion and a little less certainty.

The novel lingers on the rhythm of life, reading, and writing. How has your own routine evolved?

My routine has become less rigid and more intuitive over the years. Earlier, I chased discipline; now I try to cultivate receptivity. There are days when I’m as distracted as anyone: doomscrolling, drifting, avoiding the page. But I’ve learned to recognise the small apertures of quiet when they open. That’s when I write.

The texture of my writing life today is a mix of deliberate stillness and accidental clarity: early mornings, long runs, a window with some light, and a notebook that gathers thoughts at its own pace in a cafe. I no longer force the rhythm; I listen for it.

You’ve been more outspoken about national politics recently. How has that experience been? Has that changed how readers respond to your work or your experience as a writer?

Speaking more openly about national politics has been both clarifying and tiring. Clarifying, because it comes from a place of conviction; tiring, because public debate today leaves very little room for nuance. Inevitably, some readers approach my work through the lens of their own political assumptions. But I try not to let that dictate what I write. To those who troll me on X, I want to say that just because you may have bought a copy of my Kashmir memoir does not mean that you own my soul and voice.

You’ve written about the importance of running in your life, and Neel runs too, often to escape. What role does running play for you?

Running is the closest thing I have to a reset button. It’s a physical act that quiets the noise in my head. For that alone, I am indebted to it.