Lucinella

On the day of her death in October last year at the age of 96, Lore Segal’s final short story appeared in the New Yorker. It was the perfect send-off for a writer whose stories were first published in that magazine — in fact, it’s the kind of synchronicity that wouldn’t have been out of place in her own works of fiction, most of which were drawn from Segal’s life and experiences.

And what a life it was — Segal was born in Vienna in 1928 and at the age of 10 joined thousands of Jewish children on the Kindertransport, finding refuge in England away from the murderous Nazi regime. Segal wrote a lightly fictionalised version of these events in her first novel, Other People’s Houses.

Given the way the book didn’t adhere to any specific genre (being both autobiography and fiction) or form (it appeared as short pieces in the Commentary and the New Yorker before being published as a novel), it was clear that Segal didn’t care for her work to be boxed in something as prosaic as categories.

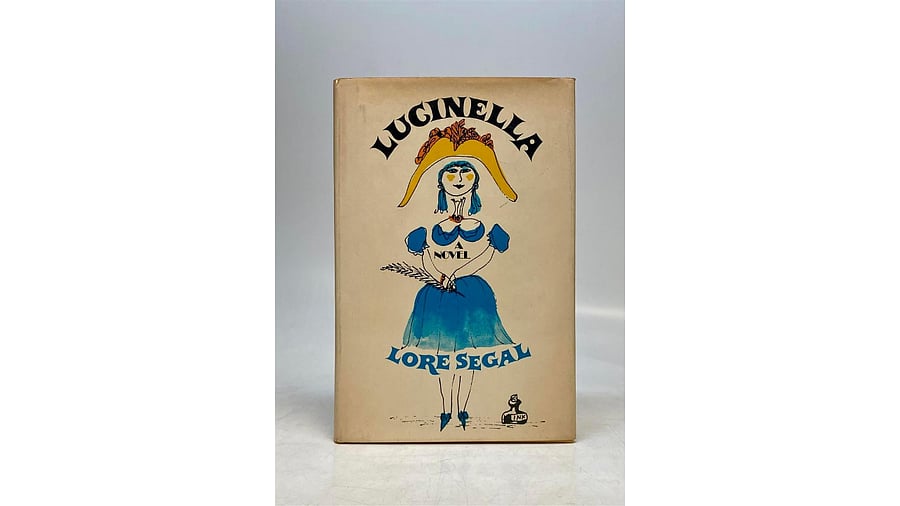

Plenty of writers have satirised the personalities and politics in the literary world with varying effect, from Michael Chabon’s Wonder Boys to Percival Everett’s Erasure and Edward St Aubyn’s Lost for Words. The publisher’s summary of Segal’s 1976 novella, Lucinella, might suggest it’s a straightforward send-up of literary egos and writing residencies, but to read it is to be constantly wrong-footed. Just when you think the story is going to zig, Segal makes it zag. Is the book about one Lucinella, the poet who’s narrating the story, or many Lucinellas who appear and disappear as and when the narrator conjures them into being or erases them from the timeline?

The answer is that the story is both — Segal leans into magic realism and flights of fantasy, eschewing conventional narrative logic. There is a sequence of events, starting with Lucinella at Yaddo, the legendary artists’ retreat in Saratoga Springs, where she encounters familiar literary types with names that wouldn’t be out of place in a fairy tale. So there are poets named Winterneet and critics named Betterwheatling, and Segal has a lot of fun skewering their pompous pronouncements and incorrigible namedropping — “Winterneet tells us about the time he drove Roethke up from the sanatorium.”

Lucinella tries to write poems at Yaddo. Occasional flashes of inspiration come upon her: “By the thunder in my pulse, I know: the Muse has struck, and in the blinding shock of the illumination I see how everything fits, the application of what I know, the relevance of anything that anybody says today, tomorrow, and for days to come.”

Back in New York, the Muse doesn’t visit her quite as often, and Lucinella, in between trying to fix up her apartment with the right lining paper on the kitchen shelves and the correct finish for the wooden flooring, falls for a writer named William, buys new pencils and notebooks, resolving to write more, attends parties where she runs into the Yaddo crowd, observes the backstabbing and petty jealousies that animate them, objects to a friend using her as a character in a story, and runs into a young Lucinella and an old Lucinella, and somehow manages to have a torrid affair with Zeus (yes, the Greek god).

It’s all a bit much for a book this slim, and at the same time, you feel there should have been more. There’s so much fun to be had just surrendering to Segal’s imagination and wit, letting yourself be carried through the story’s strangeness to an ending that is deeply poignant. There, at the end, you see Lucinella experience what she had, in the early pages, called her credo: “what can be felt can be translated into words…” As the final words and Lucinella (all the Lucinellas) drift off the page, it’s clear this was Segal’s credo, too. The only way to make sense of this life, to get at its core truths, is to write it down.

The author is a writer and communications professional. She blogs at saudha.substack.com

That One Book is a fortnightly column that does exactly what it says — it takes up one great classic and tells you why it is (still) great.