The very first India House, the headquarters of the East India Company was at Crosby Hall in London (from A.D. 1621 to 1638) and the ancient mansion is still extant as a protected monument.

For the next two centuries, the East India House in Leaden Hall Street was the main office of the East India Company and the mansion was demolished in 1861, four years after the British Government took over India, after the First Indian War of Independence (known as the Sepoy mutiny of 1857).

The Indian Reforms Act of 1919, authorised from that year, the position of an Indian High Commissioner in London to look after India’s interests namely ‘welfare of Indian seamen, the admission of students to various educational institutions, the needs of ex-British employees in India and other similar Empire oriented subjects.’ In October 1920, Sir William Meyer took charge as the first Indian High Commissioner to Great Britain.

Till 1922, four houses near Grosvenor Gardens in the vicinity of Victoria Station housed the offices of the High Commission. But in 1925 the succeeding High Commissioner, Sir Atul Chatterjee, found, that it would be economical to plan for a permanent chancery and with the help of the British Government, a 12,400 square-feet plot of land in Aldwych, the heart of London, was acquired on a 999-years’ lease from the county of Westminster.

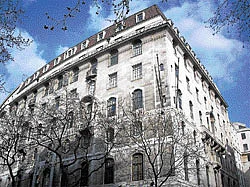

With a frontage of 130 feet on Aldwych and a frontage of 100 feet on nearby Montreal Place, this building, designed by Sir Henry Baker, was described by the London ‘Times’ as ‘‘one of the most attractive buildings of modern London.’ Planned and constructed under the orders of the Government of India, with grants voted by the Indian legislature, this building was formally opened by King George V on July 8, 1930.

In those halcyon days, this huge mansion cost nearly pounds sterling 3,30,000 or Rs 40 lakhs. Spread over five floors with the offices of the high commissioner and of the consular departments, there’s not much on the outside except for the tricolour and the name of the building in both English and Devanagri to mark out its strategic importance. But every bit within is steeped in history.

The edifice is flanked by the Strand and its buzzing theatres and restaurants on one side. Covent Garden, with the famous Royal Opera House, arcades, open air performers and market stalls is a few minutes’ walk down the road.

The exterior of the building had friezes inspired by the British Imperial Era. As you step in, the entrance hall greets you with murals depicting the six seasons of India in all their glory.

Working in a temporary studio lit by a skylight from April 1931, four Bengal artists worked tirelessly for 10 months on a pay of one-pound-a-day to complete the murals that decorate the central dome, the entrance and the main hall.

In 2005, the director of the Archeological Survey of India, on examining the murals, suggested cleaning them manually. It was then that the artisans, who had worked on the temples in Rajasthan and later at the Swaminarayan and Ealing road temples in the UK, were brought in. The balcony looks resplendent in red sandstone jali work.The main entrance is of black Swedish granite worked in the fashion of jalis and both sides of the entrance are faceted with black Belgium marble.

The wood-work is of Indian and Burmese timber and the various provinces of British India are represented by their symbols-Madras by Fort St.George. Bombay by a ship, Bengal by a tiger, United provinces by fishes and bow and arrow and so on.

The octagonal hall is of a soft pink Corsehill stone, which reminds one of the red sandstone of Fatehpur Sikri and soars up three floors to a fine marble jali-work lantern “best seen if you go up your way to the High Commissioner’s suite of rooms”.

The mural paintings of the entrance hall depict Indian scenes by R.Ukil and S.Choudhury. In 1947, VK Krishna Menon took over as the representative of Free India. He was followed by the sedate BG Kher, Vijayalakshmi Pandit, and my Indian luminaries like the eminent journalist Kuldip Nayar, have occupied the India House as India’s High Commissioner.

There have been 22 Indian High Commissioners posted to London in the 63 years since Independence. A popular story has it that Jawaharlal Nehru once got stuck inside a lift at India House. As he waited for the elevator to start up, Nehru recalled later, he thought it would be a good idea to stock some books inside the lift for such emergencies!