Independent India inherited four big metropolitan cities in 1947 — Bombay, Calcutta, Delhi and Madras. Of these, Delhi was the most unique and untypical in some ways. It was the only one that predated the British rule by a long time span. The other three were all created by the British. Delhi had a long history, by some reckoning, more than 3,000 years old.

Delhi’s prolonged prominence may have had something to do with its geographical location. It was the natural gateway of entry for travellers, traders, settlers and raiders. Most outsiders entered India through this route. Its proximity to the watershed between rivers gave it a natural advantage as an urban settlement. Delhi grew, not as one big city, but as a cluster of cities built at different points in time by different rulers who made the city their own during their rule.

Mehrauli, Siri, Tughlaqabad, Firozabad and Purana Qila were all vibrant urban centres through the medieval times. Then in 17th century, Mughal Emperor Shahjahan created a new walled city and called it Shahjahanabad. This was popularly called Nai (New) Dehli. In 1931, Nai Dehli became Old Delhi because another New Delhi was inaugurated by the British. Even today, Delhi is not one composite city, but a conglomeration of multiple settlements. The numerous villages surrounded by the cities, the old and the new, and the ancient and the modern, all coexist within this amalgam of cities called Delhi. And yet Delhi is after all one city, a city comprising many cities and many villages.

Not only does Delhi not have an organic unity, it also does not have one single overarching identity. It has been known as the seat of traditional Hinduism, as the mythical capital of the Pandavas, around 1400 BC. It is generally believed that Indraprastha was located somewhere within Delhi. During Mughal times it was the big centre of high Islam, symbolised above all by the Jama Masjid, the biggest mosque in the country. It was also a great centre of the Sufi and syncretic Islam with the shrines of major Sufi saints like Nizamuddin Auliya and Bahktiyar Kaki. In the first half of the 20th century, it had the image of a British imperial city. Finally, it became a refugee city in 1947, when, as a result of the partition, many Muslims left Delhi for Pakistan and a large number of Hindus migrated from Pakistan into the city and made it their home.

Two important features have characterised Delhi almost from the very beginning. One, the capitalhood has generally come to Delhi as its almost natural status. Two, no other city has experienced the kind of fluctuating fortunes that Delhi has. Perhaps the two features are interrelated. With the establishment of the Delhi Sultanate (1191-1398), Delhi was transformed from a provincial town into a great administrative centre. It attracted merchants, soldiers, artisans, poets and invading plunderers who flocked to Delhi with their own expectations. One of the medieval rulers, Mohammad Bin Tughlaq, decided to shift the capital from Delhi to Daulatabad in the Deccan in 1327.

The move backfired and in a few years’ time the king decided to return with all his retinue to Delhi, the ‘natural’ capital. In 1398, Timurlane, the Mongol marauder, invaded north India and devastated Delhi. He looted, killed and plundered and reduced Delhi to a lifeless landmass, devoid of all wealth and glory.

Glory restored

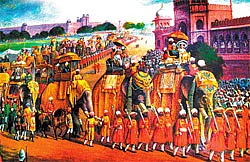

However, within a century, Delhi was back to its glory and prosperity. From 1500 till 1750 the status of a capital came to Delhi intermittently and it kept shifting between being an imperial capital and a provincial city. Eventually, it was Shahjahan who elevated Delhi to unprecedented heights of magnificence and splendour. But again, all the wealth that accumulated in Delhi attracted many raiders who once again looted, plundered and destroyed Delhi through the 18th century. Nadir Shah, Ahmad Shah Abdali, Marathas and Sikhs, all took turns and emptied the city of its riches. Some kind of order returned after the British occupied Delhi in 1803.

But the Revolt of 1857 again wreaked unprecedented havoc upon the city. All this while Delhi had continued to be India’s capital. But the British decided to create a new city of Calcutta (now Kolkata) and make it their capital.

It was perhaps understandable why the British chose the new city of Calcutta. British were the only major outsiders who entered India through its eastern border and through the Bay of Bengal. They colonised Bengal first and made Calcutta their capital. Most of the other outsiders — from Alexander to Nadir Shah — entered India through the land route at its north-western passage.

However, within a century-and-a-half, in 1911, the British too decided to shift their capital from Calcutta to Delhi and thus render unto Delhi what had become virtually its natural right. Two questions arise: Why did the British decide to shift the imperial capital from Calcutta? And why did they shift it to Delhi?

Bengal was the largest British province consisting of nearly 80 million people, almost one-fourth of all India. It included present-day Bengal, Bangladesh, Assam, Bihar and Orissa. Administratively it was unwieldy, almost ungovernable. Curzon, the new Viceroy, took the decision in 1903 to partition Bengal into eastern and western provinces. The decision to partition Bengal may have started purely as an administrative measure; it however soon turned into a huge political advantage for the British. Bengal was the nerve centre of anti-imperialist nationalism and Calcutta was seen as the centre of Congress politics. The partition move was now seen as an attempt to ‘dethrone’ Calcutta as the centre of Congress power. Risley, the British home secretary, said: “Bengal united is power; Bengal divided will pull several different ways… one of our main objects is to split up and thereby weaken a solid body of opposition to our rule.”

The main political idea behind the partition move was to break up two kinds of unities; the linguistic unity of Bengali people, because they would be in a minority in the partitioned provinces; and the potential Hindu-Muslim unity. Eastern Bengal (consisting of present day Bangladesh and Assam) was to be a Muslim majority area, with 18 million Muslims and 12 million Hindus. Muslims were told by the British viceroy that in the new province they would enjoy the kind of power that they had not enjoyed, since the days of the glory of Mughal rule. Clearly, the appeal had a psychological value and was meant to wean away Muslims from the rising tide of Indian nationalism.

Bengal partition

The decision to partition Bengal was received with almost spontaneous resentment. Many meetings were held condemning the move. Pamphlets were distributed. Petitions were signed appealing to the government not to partition Bengal. All this was done in the hope that the British government would see reason and give in to large public sentiment against the partition. The government nonetheless went ahead with the plan and announced October 16, 1905 as the day Bengal would be partitioned. Curzon, the viceroy, triumphantly declared partition to be a “settled fact” that could not be unsettled.

The partition was opposed by a huge movement that kept growing. From pleas and petitions, it moved to a boycott of British cloth, goods and institutions, and from there it developed into a full-fledged non-cooperation movement. It transformed into a movement for Swadeshi and Swaraj (home rule). It also went beyond the boundaries of Bengal and extended to Punjab, Maharashtra and some southern pockets of the country.

However, by 1908, the mainstream movement began to peter out with large scale repression and arrests of some of its main leaders. But it got diverted into a violent revolutionary direction. The decline of the Swadeshi movement had created disillusionment among the youth of Bengal who turned to individual heroism and revolutionary terrorism. Yuganter, a radical newspaper of the times, wrote: “Force must be stopped by force.” Following the methods of Irish nationalists and Russian populists, they decided to organise the assassinations of unpopular British officials and politicians. Many violent attempts, some successful and some unsuccessful, were made on the lives of some British officials. A bomb was thrown at Lord Harding, the new viceroy, organised by Rash Behari Bose.

Around 1910, discontent against the British ran high in Bengal. The government was clueless about how to handle this. Many violent revolutionaries were killed and convicted. But it was clear that the dominant mood in Bengal was uncompromisingly against the British. Should the unrest be suppressed further or should some palliatives be offered to people? That was the big question as far as the British were concerned.

It is in this context and against this background that revoking the partition of Bengal and shifting the capital from Calcutta to Delhi needs to be seen and understood.

In spite of the fact that the British had made Calcutta their capital in the 18th century, Delhi had lost none of its importance as the nerve centre of India. Till 1857, at any rate, it was the seat of Mughal authority. Its national importance was recognised even by the British. They chose to hold all their Coronation Darbars — in 1877, 1903 and 1911 — in Delhi rather than in Calcutta. Towards the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th, Delhi also developed as an important railway junction connecting routes from east, south, south-east and north-west. As Punjab increased in trade and prosperity, Delhi became a major distributing centre between Punjab and the rest of India.

As Bengal remained partitioned into eastern and western provinces, certain dramatic changes took place.

The British King Edward VII died and George V took over as the new emperor. King George had long been of the opinion that the partition had been a mistake. He was also keen on having a Coronation Darbar in India, at which he wanted to be present. At the Darbar, the king wanted to give a ‘boon’ to the people of India. The Coronation Darbar was held in December 1911. This was the first and the only time when the reigning British monarch was to visit India. King George V wanted to make this visit memorable by making a grand gesture to the Indian people. Many schemes were considered and suggested, but there was no consensus behind any. Finally, a comprehensive package was prepared at the initiative of the king.

As part of the package, partition was to be revoked, but Bengal was to be made smaller by having its boundaries redrawn. Bihar and Orissa were to be separated from Bengal. And most importantly, the imperial capital was to be shifted from Calcutta to Delhi. The last item in the package was also included keeping in view the fact that the Coronation Darbar was being held in Delhi. Once again, Delhi was going to get what had, through the centuries, been its due.

The king-emperor and the queen-empress landed at the Bombay port on December 2, 1911 where the Gateway of India was subsequently erected, and still stands there. From Bombay, the king travelled to Delhi by train. The Coronation Darbar was held on December 12, 1911 at the Kingsway Camp. Comprehensive arrangements were made to accommodate well over 2,00,000 visitors. After all the formal ceremonies were done and the Darbar seemed over, the king got up unannounced and made the dramatic declaration: “We are pleased to announce to our people that… we have decided upon the transfer of the seat of the Government of India from Calcutta to the ancient capital of Delhi...”

The dramatic declaration took everybody by surprise. Many in Bengal were happy at the annulment of the partition, but were disappointed at the loss of capital to Delhi. “They have wiped our eyes and knocked out one eye in doing so,” was one of the characteristic observations from Bengal. The mood in Delhi was ecstatic. Delhi was to return to its well-deserved glory. The construction of the new capital began under the leadership of Edwin Lutyens and finally in 1931 the New Delhi was inaugurated. Thus, yet another city was added to Delhi and after many ups and downs the honour of being India’s capital city once again returned to Delhi.

After independence, Delhi’s new-found status was questioned once again, when at the Constituent Assembly of independent India, it was suggested by some members that India’s capital should be shifted to the vicinity of Nagpur and renamed Gandhipur. Some others suggested Allahabad on the ground that it had been the bastion of Congress during the national movement. Delhi was opposed on the ground that it was after all a colonial city and had been the graveyard of old empires. But, as it happened, Delhi had more supporters than opponents in the decision-making circles and thus retained its ‘natural’ status as the capital of India.

And so Delhi lives on, accommodating within itself multiple cities, multiple images and multiple identities. It was destroyed many times, and every time it rose from its ashes like the proverbial phoenix. What gives Delhi its distinct advantage and tenacity — climate, geography, natural resources, commerce, politics, or something else? We may not know the full answer. In the meanwhile, Delhi keeps growing, scaling new heights and acquiring new aspirations.

most importantly, the imperial capital was to be shifted from Calcutta to Delhi. The last item in the package was also included keeping in view the fact that the Coronation Darbar was being held in Delhi. Once again, Delhi was going to get what had, through the centuries, been its due.

The King-Emperor and the Queen-Empress landed at the Bombay port on December 2, 1911 where the Gateway of India was subsequently erected, and still stands there. From Bombay, the king travelled to Delhi by train. The Coronation Darbar was held on December 12, 1911 at the Kingsway Camp. Comprehensive arrangements were made to accommodate well over 2,00,000 visitors. After all the formal ceremonies were done and the Darbar seemed over, the king got up unannounced and made the dramatic declaration: “We are pleased to announce to our people that… we have decided upon the transfer of the seat of the Government of India from Calcutta to the ancient capital of Delhi...”

The dramatic declaration took everybody by surprise. Many in Bengal were happy at the annulment of the partition, but were disappointed at the loss of capital to Delhi. “They have wiped our eyes and knocked out one eye in doing so,” was one of the characteristic observations from Bengal. The mood in Delhi was ecstatic. Delhi was to return to its well-deserved glory. The construction of the new capital began under the leadership of Edwin Lutyens and finally in 1931 the New Delhi was inaugurated. Thus, yet another city was added to Delhi and after many ups and downs the honour of being India’s capital city once again returned to Delhi.

After independence, Delhi’s new-found status was questioned once again, when at the Constituent Assembly of independent India, it was suggested by some members that India’s capital should be shifted to the vicinity of Nagpur and renamed Gandhipur. Some others suggested Allahabad on the ground that it had been the bastion of Congress during the national movement. Delhi was opposed on the ground that it was after all a colonial city and had been the graveyard of old empires. But, as it happened, Delhi had more supporters than opponents in the decision-making circles and thus retained its ‘natural’ status as the capital of India.

And so Delhi lives on, accommodating within itself multiple cities, multiple images and multiple identities. It was destroyed many times, and every time it rose from its ashes like the proverbial phoenix. What gives Delhi its distinct advantage and tenacity — climate, geography, natural resources, commerce, politics, or something else? We may not know the full answer. In the meanwhile, Delhi keeps growing, scaling new heights and acquiring new aspirations.

(The writer teaches history at the Ambedkar University, Delhi)