Mangalore-born Manjunath Kamath - whose earliest memories of dabbling in art is as a 4-year-old who would scribble, paint and draw on the cowshed walls in his ancestral village of Bantwal - is once again reliving his childhood he gives up the canvas to paint directly on the walls of the 2000-sq feet Gallery Espace in New Delhi.

The week-long special project will allow the audience to interact freely with the artist, who is then taking forward his penchant for the uncommon by painting local folklore on the walls of Pratappur village in Rajasthan in tandem with fellow artist Chintan Upadhyay in December.

“I have always wanted to break free of working in a studio to create what is supposed to be “market friendly,” says the 38-year-old artist who now lives in Delhi, “I have been wanting to do this project where viewers can walk into my working space, interact with me, share my thought process and even contribute to what finally emerges on the gallery walls. Since no one can buy this art, I feel free to create what I want without worrying about the commerce of it all.”

Titled ‘Conscious Subconscious’, this special project at Gallery Espace breaks down traditional norms of an artist locked away in a studio for months to perfect a painting. But then, Kamath has always followed the trail of idiosyncrasy.

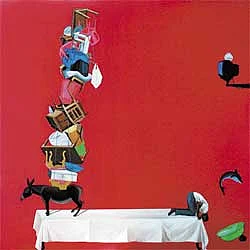

His large scale ‘humanscapes’ have always been colour intensive works that are an eclectic mix of fantasy and realism. Featuring symbols of urban pomposity to rustic memories, curious images take birth on his canvases, which replete with visual puns often read like a story.

Holding a Bachelor’s degree in sculpture from Chamarajendra Academy of Visual Arts, Mysore, Kamath remembers how his first solo show in 1996 at Shridharani Gallery in Delhi titled ‘About Something’ shook everyone up not only because of the expanse of his work but also for its quirky and satirical take on human life.

“I had concentrated on images that are left behind both in our memory and on the walls of our houses when we shift home,” says Kamath, amused at being asked what his “inspiration” has been.

“I find my images from the immediate surroundings as well as from the collective memories of the nation. Anything and everything becomes a resource for me. My works can be called ‘archival images’.” He recollects a museum visit where a broken Ganesha idol gave him the idea for one his best-known works so far. Titled ‘Looking for evidence’, the 6x6 feet canvas had a donkey captured inside a glass box with a stone lying near the animal’s feet.

“Historians would have interpreted even that small stone, someone probably threw at the donkey, as a historical artefact…that’s how our history changes based on what our perception of reality is!” According to Manju, as he is fondly called by friends, history has its own movement and “an artist’s vision lies in finding out the dynamics of history.”

However, combining history with humour does not make Kamath’s works just comical pieces. Instead, they offer a world wisdom that is sometimes lacking even in more traditional art. For instance, in one of his sculptural pieces, Kamath juxtaposes the erotic images of Khajuraho with those of a village wrestling scene calling both of them as ‘wrestling’.

The quirkiness of his philosophy is evident also in the sculptural installation of human body parts which he calls ‘Many Egos’. Kamath’s work titles not only become an entry point into his work but guide at the same time. In yet another set of sculptures, Kamath had made a series of busts of elderly gentlemen who look clever and authoritarian.

“These are just ordinary people with no noteworthy history but could become important if their busts are cast in bronze,” he laughs. It is an interesting take on imperialist history that has provided us with too many must-have-beens, and his most popular series of digital prints has a similar tongue-in-cheek treatment of what history means to the artist.

In a large digital print titled ‘Paneer Pizza’, Kamath had used tantalising images of Superman, an ascetic, a woman from the Raja Ravi Varma school, animals and much more juxtaposing them with modern symbols of advertising from foreign magazines. In yet another work titled ‘How Come He is Here’, he takes traditional images of Ravi Varma characters, one of them holding a donkey’ s tail that points at a monkey, while even having a man ride a scooter! “We can question anyone and everyone’s existence in this work. Why are we here in the first place?’

So successful has Kamath been with his unabashed mockery of “global lifestyles” that his work in the much acclaimed Marvellous Reality show held in Delhi last year became the talk of the town for weeks. Take for instance, his sculptural installation titled ‘Second Hand Car goes to Heaven’, made of handmade fibre glass rabbits that seemed to be getting sucked into the exhaust of an upturned car fixed on the ceiling. While increasing city pollution would occur as the theme to an onlooker, Kamath asks you to dig deeper.

“Notice how the rabbits are multiplying just as our population is!” Just like his art, where real meets the unreal, Kamath’s studio in Delhi’s upmarket Hauz Khas village is a meeting ground of two worlds. Kamath is working on a computer, as much at ease as he is with wet clay and paint, the former he mastered as an illustrator with The Economic Times in early 90s, after he returned from a Charles Wallace Scholarship, UK.

“I have dabbled in all sorts of mediums, including video art. I get bored easily with one style,” says the artist whose best-selling series of digital prints also created a splash during the Art Summit in Delhi last year. Titled ‘Overdose’, the 9 feet by 12 feet limited edition print, also shown in Korea later, boasted of over 50 characters drawn from various periods of world history.

Interested more in deconstruction of memories than in construction of an image, Kamath’s canvases, however big they may be, are sparsely habited and the vast flat surfaces look like an undefined area left to be defined and determined by various historical processes. “The images that I build in these flat surfaces are just clues for interpretations. They could be the remnants of a deconstructive process,” says the artist.

Just as you begin to wonder if the artist has made large size his USP, he fetches bundles after bundles of postcard size drawings. “One drawing gives birth to another,” says the artist. “Every little thing inspires me and I convert it rapidly into these small drawings. But these are not simple images of what I see,” he says and adds, “I look at the history of an image or object before I absorb it into the repertoire of my images.” 100 such small drawings are being shown in Taipei Museum later this year.

Recounting the story of a lady who came to his studio asking for something “different”, he laughs at the drawing that emerged from that meeting. “A stuck up nose with two fingers inside the nostrils is what I gave her,” he says, “it was different indeed!”

Laughing at himself (“I never thought I could make a living out of art”) and others around him, Kamath’s forte ultimately lies in creating fantasies out of the ordinary.