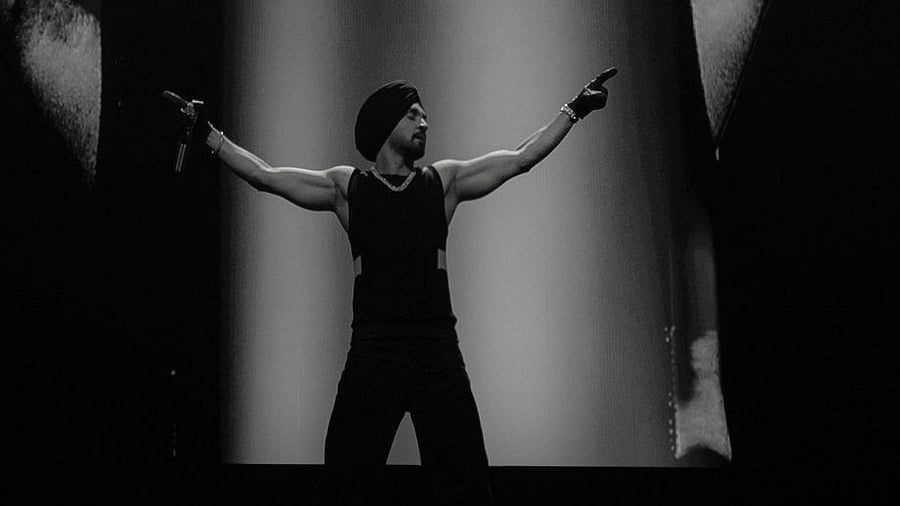

Singer and actor Diljit Dosanjh at a concert.

Credit: X/@diljitdosanjh

Bengaluru: Following an exhilarating few hours having listened to their favourite artists live, large numbers of concertgoers begin their commute home on the metro train. All of a sudden, a traveller hums a familiar tune, and something happens — one by one, the chorus picks up voices, and the carriage fills with excited singing.

“It was a surreal experience,” says Diya Rajan, a 28-year-old from Bengaluru. On her ride home from Bandland, a music festival organised in November, passengers began singing songs by Avenged Sevenfold, one of the artists at the festival. Similar videos of concert attendees crooning were widely circulated online following performances by Coldplay, Ed Sheeran and Diljit Dosanjh in India.

Behind the excitement, a diligent workforce ties together these systems of safety, sanitation, technology and infrastructure, with hours of toil. In fact, this group stays back long after the singing commuters have gone home or flown back to their cities.

In the past decade, there has been a marked increase in demand for live music events, says Tej Brar, festival director of the NH7 Weekender, who been associated with the music festival since 2011. “More audiences have come to expect international talent to visit. Now, the frequency has multiplied, with cities seeing global artists every month, and live music shows every week.” he explains. The availability of information online and on social media, as well as avenues to book tickets virtually have further boosted interest and attendance in the space.

There is no doubt, India’s fast-growing, high-revenue concert economy impacts thousands of people and businesses. Hotels, local stores, transport companies and q-commerce services see surges in both demand and pricing. According to data from BookMyShow, 2024 witnessed an 18% growth in India’s live entertainment consumption, with 30,687 live events across 319 cities.

“Live entertainment and live music concerts are certainly seeing a massive resurgence in India. This is not just a one-time phenomenon, but something we are witnessing over a vast spectrum, right from smaller capacity and intimate concert gatherings to large-scale stadium-sized gigs,” says Anil Makhija, COO, Live Entertainment and Venues, BookMyShow.

With more big-ticket artists lined up and currently visiting, including Ed Sheeran and Shawn Mendes, the ticketed live music segment is expected to reach Rs 1,864 crore this year. It is no surprise then, to see the government’s recent statements on reaping the economic benefits and being equipped for the challenge.

Profits and problems

In some cases, efforts seem to have already paid off. Coldplay's concert here on January 25 and 26 drew over 1.11 lakh attendees each night. The state government was quick to cash in on the positive reviews.

The two days of Coldplay in Ahmedabad alone were expected to generate more than Rs 300 crore in business, said Harsh Sanghavi, Minister of State — Home, Industries, Transport, Youth and Sports in a statement.

Yet, with the large concert sector being relatively nascent, and with the scale growing exponentially, it is not without hiccups.

In Hyderabad, for example, at the recent Ed Sheeran concert held at Ramoji Film City, attendees complained about the lack of lights in the temporary washrooms. “Also, an hour before the show started, the toilets were already completely unusable,” says one attendee. Others complained about losing money due to faulty digital transactions on the wristbands — a common system of payment at concerts, where one scans a QR code on the provided wristband, and tops it up with money to pay for food and water.

“Both before and after the concert, traffic was a major issue. Exiting was a huge headache because even though there were several expansive parking lots, traffic was directed towards a single exit. And for those using cabs, drivers began demanding up to Rs 2,000, when the fare was only Rs 700,” says a fan who had flown in for the concert from Bengaluru.

While there were plenty of support staff and volunteers for smooth functioning, there seemed to be few arrangements for them. “Cleaning staff were standing around the venue, and were even seated on the ground, as there was no seating. They had been at the venue well before the event began, and probably had to stay there to clean up for hours after,” she adds.

At the Coldplay concerts in Navi Mumbai, 100 municipal body staff and 150 volunteers worked to clear the waste from 10:30 PM to 2 AM. The Navi Mumbai Municipal Corporation (NMMC) had a gigantic amount of waste on its hands — it collected over 100 tonnes of garbage in and around the D Y Patil Stadium. The stadium, with a capacity of 75,000 people, had been jam-packed on all three days.

In addition to concerning levels of waste generation, when public infrastructure is not up to the task, large-scale music events also cause other disruptions, says Sandhya Surendran, a media and entertainment lawyer based in Bengaluru. “We also have to think about how the events impact people who do not attend, particularly in terms of traffic and transport facilities.” She cites the example of Bengaluru’s Palace Grounds, which sees intense gridlocked traffic, particularly when a wedding, a concert and peak hours come simultaneously.

There are also concerns about indiscriminate ticket pricing, resale of tickets and scalping. Yet, events continue to have a large number of takers, beyond attendees, among organisers and the administration too. Many point to the undeniable economic benefits that come with the increased footfall.

Rasananda Panda, a professor of economics and management at MICA, Ahmedabad, says such tours increase the GDP of the country in the short to medium term, by increasing individual spending. "The demand for concerts is the result of increasing aspiration of people in the country, backed by discretionary purchasing power — especially that of Gen Z. It is also a sign of a growing state or country’s soft power," he adds.

In 2024, BookMyShow reported a rise in ‘music tourism’, with over 4,77,393 fans travelling beyond their cities to attend live events. “The tickets are mostly affordable, but you pay for the experience you want to have. In a different city, ideally you would want to do some sightseeing in addition to attending the concert. So you would spend at least Rs 60,000 overall. In your own city, it would be about Rs 15,000 including tickets, transport and food,” says Sanam Jiandani, a 27-year-old artist who attends and helps organise live music events in Bengaluru.

The increase in spending is not without detriment, Panda explains: “The events are also responsible for an increase in inflation in the country or a specific location, leading to a price rise of essential commodities that become scarce during the concert days.”

Local involvement

Concerns about impact on local life and environment are particularly pertinent in ecologically sensitive regions like the northeast. This is why locals were hesitant in 2012, when the Ziro Music Festival started in the picturesque Ziro Valley in Arunachal Pradesh, says Boby Hano, one of the organisers.

But over time, as the festival grew in popularity, it became clear that it was bringing positive changes too. “Local businesses, artisans and service providers have been able to generate an income from the influx of visitors, leading to better livelihoods,” Hano explains.

The festival is known for its focus on sustainability and inclusivity, and draws about 15,000 people every year. Locally available materials such as bamboo are used in order to reduce its impact on the environment.

Community participation proves to be a key part of ensuring maximum benefit, with minimum harm. Take for instance, Nagaland’s Kisama heritage village, where the famous Hornbill Festival completed 25 years last December. It drew more than two lakh visitors this time, a 33% increase from the previous year.

It is the biggest event organised by the state government with the help of organisations representing all 16 Naga tribes. "It is because of participation of the local community and the state government," says Kaushik Das, a tour operator from Assam. He puts up tents during the 10-day-long cultural event. His tents are priced between Rs 1,000 to Rs 1,500 per person per night.

Trends in demand

From Ahmedabad to Kohima to Coimbatore, demand for live music events on a large scale has also trickled significantly to tier-2 and tier-3 cities. Tier-2 cities such as Kanpur, Shillong and Gandhinagar have also seen exponential growth in live entertainment, with a 682% surge in events, year-on-year, according to BookMyShow.

In Tamil Nadu, concerts which were earlier confined to Chennai, are now being held and drawing crowds in towns like Coimbatore, Madurai, and Tirunelveli. “We will only see the demand going up. This is an emerging business and we want infrastructure for it to be developed,” a local event manager tells DH.

The state also sees high demand for homegrown acts like Ilaiyaraaja and A R Rahman. Chennai is now getting ready for India’s first live-in dance concert by ace dance master Prabhu Deva. The tickets are priced between Rs 1,200 and Rs 29,500.

Amidst the boom, many question if the city is equipped to deal with the crowds. In September 2023, A R Rahman’s live concert Marakkuma Nenjam (Can the heart forget?) exposed the lack of adequate infrastructure, as well as gaps in regulation. Organisers had made seating arrangements for 20,000 people, but sold over 35,000 tickets for the concert on the scenic East Coast Road (ECR).

Thousands of people arrived late to the concert due to massive traffic jams. At the concert venue, chaos had broken out due to poor organisation and overcrowding. Several women reported being groped.

The Chennai Metro Rail Corporation (CMRL) is attempting to provide a transport solution, by tying up with organisers of events at the YMCA grounds to provide free travel for people attending such large events. “We see a good number of people using the metro to come for concerts at YMCA as the venue is less than a 500-metre walk from the station,” a CMRL official says.

Interest from artists

The present attention directed towards India’s concert economy and its steep growth trajectory do not stem just from recent efforts, say those involved in the space. “It started more than 10 years ago, when international artists, and particularly DJs and electronic music artists began to do shows in India,” says Tej.

Contrary to popular assumption, sound, lighting and musical instruments across the country are advanced, say musicians and organisers. “You have vendors across India for staging, sound and the like. The quality and scale of technology is just as good, if not better than international events. We have very good vendors who have invested in inventory, sound systems, LEDs,” he adds.

Interestingly, one key driver of such improvement has been the Indian wedding industry. The scale of the wedding industry is so heavy and demand has increased so dramatically, that it makes sense why vendors have invested, he adds.

Significant improvements in the past five years have proved encouraging for artists too, says Jason Sharat, a Bengaluru-based drummer. “I have played shows in China, Thailand and Singapore. In terms of drum kit maintenance and technology, India is on par,” he says.

The emergence of quality vendors across the country is a huge boon as well, he adds. “Previously, good gear was only available in metro cities, but now even in places like Mangaluru, you can find really high-quality gear, and reliable vendors.”

Another boost has come in the willingness on the part of the government to collaborate in events and entertainment. Organisers point to the willingness of the Sports Authority of India to open up the Narendra Modi stadium up for the Coldplay concert.

Despite the country boasting numerous state-of-the-art cricket and football stadiums, their use beyond sporting events has remained underutilised. “We are actively collaborating with sports associations to shift this paradigm, optimising stadium usage for large-scale entertainment while ensuring minimal disruption to their primary purpose. This includes strategic ground planning and advanced turf protection methods,” says Anil.

Continuous progress and investing significantly in infrastructure are important to establish India as a fixed destination on global tour routes of international artists, he adds.

“A prime example of this is our work at Mahalaxmi Racecourse in Mumbai, where we collaborate with authorities to make the space consumer-friendly and ready to use. We are actively working with authorities to streamline this process, aiming to upgrade the Racecourse into a plug-and-play venue of world-class standards. This effort is what enables the space to host major international festivals,” Anil explains.

Gaps remain

From anecdotes across the country spanning recent years, it is clear that the concert industry has seen significant growth, but is also filled with worrying gaps. There are numerous examples on both sides of the spectrum of ecologically destructive versus sustainable, affordable versus exploitative, safe versus chaotic and supportive of the local community versus disconnected.

The lack of regulation in the space is a major concern. “Beyond the licensing, there is no comprehensive policy or body that regulates how live music events are organised. This leaves it up to the organisers,” says Sandhya. This is why there are significant differences in representation of local artists and women, accessibility, security and safety across concerts.

There have been successes: Many cite the example of the sustainable and inclusive Echoes of the Earth music festival, an annual feature in Bengaluru. The festival prioritises using renewable energy, biodegradable materials, and also ensures artist lineups are diverse and representative.

But many popular events see little to no conversations around sustainability. Some studies estimate that a concert sees the generation of 5 kgs of carbon emissions per person per day. Fans cite efforts by artists like Ed Sheeran and Coldplay to reduce their carbon footprint. At the Coldplay concert, all confetti used was biodegradable, and required less compressed gas for ignition. The wristbands were also made using recycled material, and according to the band’s sustainability report, 86% of them are returned and reused.

Another initiative growing more common is the provision of plantable seed paper with the delivery of tickets.

While small steps such as halving carbon emissions are valuable, environmental activists point out that other measures such as banning reusable bottles at venues, serving food in plastic packaging, and generating tonnes of waste at each event undermine and contradict this sustainability.

The lack of a standard operating procedure, and guidelines for this scale of events is a significant gap.Without uniform monitoring mechanisms, exorbitant ticket rates, overbooking and overcrowding are only some of the issues that plague many events.

The standards for treatment of artists, as well as artist and vendor payments, are also overlooked in the regulatory framework. “I know popular venues that have not paid artists for even eight years. Most times, when an artist brings it up on social media, the venue immediately responds to the outrage and pays the artist,” says a local musician. This could prove a significant deterrent, especially for smaller, up-and-coming, and global artists.

On the ground, organisers cite run-ins with police and government officials who demand bribes to move the permit process forward. In some instances, even permits fall short, with last-minute run-ins. Many point to last year’s cancellation of a major music festival, only hours before it was set to begin. “All the permits had come through. Artists had all been flown down, attendees were literally lined up at the gates, but the cops refused to give the NOC for the event to proceed,” says a performer. Ultimately, the event had to be cancelled, and organisers, artists and attendees underwent significant losses.

Such problems are not so rare. “Police just show up, vaguely mention noise complaints or other random issues, only to demand money to allow the event to proceed,” the performer adds.

“I was at a recent event that was shut down as early as 10 PM, despite having all the necessary permissions well in advance. The event was organised in collaboration with the state government and tourism department. Yet, police showed up, created a ruckus, and even took one of the artists to the police station. This was an artist’s showcase, with guests from all over the world. Amid the talk of this global concert economy, imagine the impression such harassment would have,” says Sandhya.

A solution in the short term could be the setting up of a strong association of private players in the fields, she recommends. “A self-regulatory association can be put together, along the lines of associations for restaurants and trade bodies. This would go a long way in establishing a general code of conduct,” she adds.

From the policy perspective, changes require more long-term involvement. “This includes how states and the Centre will incentivise the organisation of large-scale music events.” Alongside this, there is also a need for accountability and clear standards for ticketing processes, regional representation, safety measures and on-ground checks, she adds.

For organisers, simplifying the licensing process would be key: “There has been talk of a single-window license system for large format events. This would really help, as currently, we need to get 18 different licenses from various departments including the fire department, traffic police, police and the foreign office, to name a few,” says Tej.

India’s concert ecosystem has seen a gradual and strongly founded growth trajectory. As the space continues to evolve, it is essential to prepare for the growth, and ensure it is not held back by gaps in infrastructure, monitoring and sustainability.

(With inputs from E T B Sivapriyan in Chennai, Mrityunjay Bose in Mumbai, Satish Jha in Ahmedabad and Sumir Karmakar in Guwahati)