This comprehensive account of life in Annawadi, a Mumbai slum, is a story woven around characters who are real life individuals, and of a type found all over India, writes AVS Namboodiri

Katherine Boo’s Behind the Beautiful Forevers is at once reportage, history and social documentation, the kind of which is written only once in decades. It is an account of life in a Mumbai slum, Annawadi, and is most faithfully portrayed and comprehensively real. But the reality it explores and presents is stranger than fiction, and terrifyingly so.

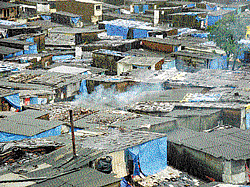

Annawadi becomes a metaphor for a poor, corrupt, struggling, violent India that exists side by side with the opulent glass towers and glitzy supermarkets that peak into the Forbes’s lists and an acclaimed superpower future. It is a world recreated with its own stark elements and characters, events, emotions, and all things human. We know Marquez’ Macondo or R K Narayan’s Malgudi which are fictional places which appeal as real. But here is a real place which shames fiction, with the cruel world of Adiga’s White Tiger appealing only as a shadow of the real.

The book is a seamless narrative based on Boo’s observations, conversations and interactions with people in Annawadi, a slum near Sahar’s new international airport and a number of high-rise luxury

hotels. It is peopled by men, women and children, migrants from poor parts of Maharashtra, workers from Tamil Nadu and bhaiyas from UP. Boo, a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and staff writer for New Yorker, followed their lives and studied them for four years keenly and unobtrusively.

They are rag-pickers, drunkards, prostitutes, teachers, all jostling for life and space in a rat race of crime, oppression, insensitivity, corruption and official neglect, but driven by the survival instinct, some enterprise and slim hope.

Abdul is a teenage scrap sorter who has to look after a family of 11, Sunil, a scavenger raised in an orphanage, Raja, a cleaner of public toilets. They are also hardened and made street-smart by experience. They are all in collusion with the agents of the state who appear and intervene in their lives. Policemen take their dues, government hospitals demand money for supposedly free treatment, bank officials want their commissions and municipal staff want records falsified.

Asha is a woman from Vidarbha who is only a ‘seventh class pass’ but gets a teacher’s job with the help of local politicians she is close to. She organises a self-help group and gets cheap loans which are given away to poor women on high

interest rates. She does favours for people using her political influence and takes her commission. Her daughter, Manju, will soon be the first female college graduate from the slum. Boo starts her story with Abdul’s aspirational family which lost its garbage business in a strange sequence of events starting with a fight with a one-legged woman neighbour. The woman sets herself on fire and the family is accused of murder and has to spend time with the police and the courts.

Boo has woven a story with these and many other characters who are at the same time real life individuals and types found all over India. There is corruption which is not redeemed, ambition which is killed by jealousy, hope which goes unfulfilled but never dies and abject poverty which propels people to do anything.

It is not always that the life of a small community gives a picture of the life of a billion people of a subcontinent in the throes of change. Boo succeeds exceedingly well and many of her insights and observations are more important than the conclusions of many well

researched studies of poverty and development in India. The questions she manages to raise are moral, political and social, and they are all basically human.

She is to her very bones the inquisitive journalist and is unsentimental, but not devoid of sympathy. There is no cynicism and subjectivity. In fact, the first person never comes to the fore and talks to the reader. The language is clinically clean and without embellishments but expressive and evocative, and the quality of writing, excellent.

She did painstaking work for her book, conducted hundreds of interviews between 2007 and 2011 and waded through tens of thousands of records, many of them procured through the right to information route, and linked all the information in a very human story. The question why more of our unequal societies do not implode may not have been answered fully in her book but there is a serious and sincere attempt to find the answers in this book.

This is recommended reading for all our policy-makers, ministers, legislators, bureaucrats and others who are interested in India, and it should be provided in translation for those who do not understand English. It busts many myths we have held dear and true, and opens up a new world to the reader. And imagine, it had to be written, in a country teeming with journalists, economists, social critics and development experts, by an American.