It interviews nearly everyone involved in it, including the guy who whistled for all those irresistibly hummable Ennio Morricone tunes. The story of the spaghetti western has been documented often in books, but cinema is th

e most natural place for this tale to be documented, making this movie a great idea. For so many Indian movie aficionados, the spaghetti western was close to religion.

I don’t think we cared too much for the pure-bred American westerns — what does Stagecoach or The Searchers or High Noon really mean to us? It’s Django, The Good, the Bad, the Ugly, Death Rides a Horse, Sabbata, Ace High, and the Trinity movies that defined the western for us. The only American western that was something of an icon for us — McKenna’s Gold — is considered a dud. And the other Indian favourite, The Magnificent Seven, is really a Japanese Samurai fable.

One day, a rather young Clint Eastwood called a few of his close friends and screened A Fistful of Dollars, warning them beforehand that it would be bad, possibly awful and shitty. It had yet to come out in movie theatres. A little into the movie his audience turned around and told him it looked not just good, but pretty great. No one was more surprised than Eastwood.

In this documentary, however, we hear Eastwood say that he thought Leone had not only a sense of humour but great visual sense as well. But the thing is nobody, not even its star, knew what would come of Sergio Leone’s crazy experiment. Sergio Donati, its scriptwriter, talks of its origins: Leone called him out of the blue one day and asked him to go see Kurosawa’s Yojimbo. Donati was puzzled — a Japanese art film? “We can make a western out of it,” Leone told the even more surprised Donati. A western in Italy from a Japanese movie? Leone just knew there was something pulpy about Yojimbo and its only later, of course, that they all found out that Kurosawa himself was possibly inspired by the hardboiled Red Harvest stories of Dashiell Hammett.

James Coburn and Charles Bronson wouldn’t act for 15,000 dollars — what Leone could afford — so they picked the unknown kid from a television series and turned him into The Man with No Name. For dialogue, the actors were told to count numbers — later English would be lip-synched. Also, a minimum of dialogue with long, drawn out and tense silences. This became the genre’s convention, but it was, to begin with, convenient because most of the cast and crew didn’t know English. Spain stood for American landscapes, and the Mexicans peasants were played by Spanish gypsies. Leone had fun shooting it, making up his own rules. He set up those exciting draws and shootouts in widescreen.

Magnificent success

It released in Italy as The Magnificent Stranger. Eastwood went back to Hollywood, and struggled as an unknown, forgetting all about the movie. Then he began to hear it was a box office rage in Europe. And then in North Africa, East Asia, and finally, India. Everyone was whistling the movie theme. Leone had heard two country records made by a composer called Ennio Morricone and had loved it. Morricone says that once he had made the music for Leone, he didn’t want to repeat the same stuff for the other Sergios — Corbucci, Sollima and Donati. And it’s true: The music from the non-Leone spaghetti westerns don’t sound anything like the Dollar trilogy tunes.

Brilliant British film critic and filmmaker Alex Cox says in the docu that the Leone movies are inferior to the work of Corbucci — that Django with Franco Nero is truly violent, not just romantic, pushing the spaghetti western as far as it could go. And a movie by Corbucci he names — one that possibly didn’t come to India, The Great Silence — he considers the greatest spaghetti western ever made. (Corbucci’s Companeros played in Bangalore).

Stars in Italy

In this unbelievable western, the wounded hero, a mute, returns to take down the villains only to be shot down! Aspiring European character actors and failed American actors became stars in Italy. Franco Nero, Klaus Kinski, Lee Van Cleef, Jack Palance and Eli Wallach became so popular in Europe, that no matter what movie they made, they were always called Django this or Django that.(!)

The way it works in Italy, explains Donati, is that a genre becomes a craze until there is overkill, and a new genre takes its place to become all the rage. The spaghetti western took the place of historical fantasy movies such as Hercules vs. Zorro. And now the spaghetti western was being exploited to the maximum. It had to die, and the movies that killed it were, interestingly, a series of movies most beloved to Indians.

The Italian industry wanted to repeat the success of the Dollar movies, and were desperate for another star like Eastwood. They found one in Mario Girotti, who looked like both, Eastwood and Franco Nero. And gave him the screen name, Terrence Hill. The titles sound more fun in Italian: Lo chiamavano Trinità, and Continuavano a chiamarlo Trinità. The comedy in the Trinity-Bud Spencer movies came close to parodying the genre than revitalising it.

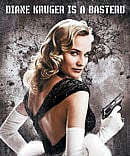

As this genre faded, a new cycle of movies began to grip the Italian imagination: Gory, sexy slasher films with one name leading the pack: Dario Argento. And so the western died on screen, but has endeared itself on DVD and in film festival retrospectives. No one knows how it came to be called spaghetti — the best film historians can do is second guess that it probably came to be called that dismissively by film critics. Well, further and ultimate proof that it lives on, in spite of critics, is Quentin Tarantino’s new film, just shown at Cannes to standing ovation: Inglorious Basterds (yes! basterds not bastards) a Spaghetti western re-imagined as Nazi revenge fantasy! I know these spaghetti movies too well to see them again, but the Ennio Morricone tunes are not just movie soundtrack masterpieces, but the genre’s greatest legacy to world cinema.