Ken Kesey’s celebrated novel, ‘One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest’, published 50 years ago, was made into a critically acclaimed film. But the author refused to watch the movie ever, writes Giridhar Khasnis

The first issue of the first weekly news magazine in the United States, Time, came out on March 3, 1923. Eighty-two years later, in October 2005, the magazine unveiled a list of 100 best English language novels published between 1923 and 2005; the list was chosen by critics Lev Grossman and Richard Lacayo.

Among those that made it to the list was Ken Kesey’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. Explaining its inclusion, Grossman said that Kesey (1935 -2001) had taken on the hypocrisy, cruelty and enforced conformity of modern life in his boldly anti-establishment novel set in a mental asylum.

“In Cuckoo’s Nest, the irrepressible inmate Randle McMurphy does battle with the icy, power-mad Nurse Ratched to liberate, or at least breathe a little life into, the crushed and cowed patients she lords it over, while the book’s stonily silent narrator Chief Bromden looks on,” wrote Grossman. “Both an allegory of individualism and a heart-tearing psychological drama, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest manages to be uplifting without giving an inch to the seductions of sentimentality.”

Published by Viking Press in early 1962, the critically acclaimed novel instantly became a rage with the counterculture movement in America. While The New York Times described it as “a glittering parable of good and evil, a work of genuine literary merit,” Time magazine called it a brilliant first novel, “a strong, warm story about the nature of human good and evil, despite its macabre setting.” Decades later, a critic remarked that Cuckoo’s Nest was driven by the great binaries of sane and insane, male and female, free and captive.

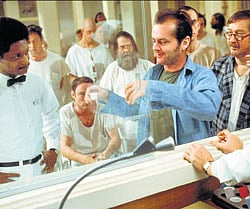

Cuckoo’s Nest was adapted into a Broadway play by Dale Wasserman in 1963. Twelve years later, it was made into an award-winning film directed by Czech émigré Miloš Forman, starring Jack Nicholson as the ebullient McMurphy; Louise Fletcher as stony Nurse Ratched; and Will Sampson as the silent witness, Bromden.

Produced by Saul Zaentz and Michael Douglas, and premiered on November 19, 1975, the 133-minute film became a runaway success. Besides collecting six BAFTA awards and six Golden Globes, it won all five major awards at the Oscars: Best Picture, Best Actor (Nicholson), Best Actress (Fletcher), Best Director and Best Adapted Screenplay (Laurence Hauben and Bo Goldman). The previous film which had won those five Oscars was Frank Capra’s It Happened One Night, premiered way back in February 1934.

Box office hit

Hailed as one of the best-known anti-authority films in history, Cuckoo’s Nest became a huge success at the box office. Produced at a meagre budget of about $4 million (a significant portion of which went to pay Nicholson), it grossed over $110 million after release.

Writing in The New Yorker, movie critic Pauline Kael recalled that the novel had preceded the university turmoil, Vietnam, drugs, the counterculture; yet contained the prophetic essence of that whole period of revolutionary politics going psychedelic. “Kesey’s novel was a lyric jag, and it became a nonconformists’ bible... The movie retains most of Kesey’s ideas but doesn’t diagram them the way the book does... Milos Forman replaces the novel’s trippy subjectivity with a more realistic view of the patients which leaves their mental condition ambiguous.”

Curiously, Kesey never got along well with the producers of the film. Among others, he disapproved the script and choice of Nicholson for the main part. He even sued the producers for five percent of the movie’s gross and $800,000 in punitive damages and eventually won a settlement.

In fact, it was Kesey who was first contracted to do the screenplay by the producers, “but they wanted me to do it a certain way, leaving out the narrative thread of Chief’s perspective and making Big Nurse the centre of evil.” So the deal didn’t come off.

On his part, Forman felt that while the book was great literature, Kesey’s script was just illustrating the book verbatim and wouldn’t have worked for the film. Forman was certain that only Nicholson — a well-known face — could fit the bill for the lead role. As for the rest of the cast, he interviewed more than a thousand actors because he “wanted everybody in that mental institution to be an unknown face.”

Kesey refused to ever watch the picture. “I’ve never seen it,” he said in an interview decades later (The Paris Review / Spring 1994). “We were arguing with lawyers and the issue was whether I had been paid adequately. I was fussing with them. They said, why are you coming on like that, you’ll be the first in line to see that movie. I said, I swear to God I’ll never see that movie. I did it in front of the lawyers and I’d hate to go to heaven and have these two lawyers calling me on it.”

Origins of the novel

It is well-known that Kesey was inspired to write Cuckoo’s Nest after he volunteered for Army-funded hallucinogenic-drug experiments in a psychiatric ward at the Menlo Park Veteran’s Hospital in 1960 where he experienced the effects of an array of drugs including mescaline, Ditran and LSD. He also became a night aide on the psychiatric ward at the hospital and came to observe the inmates. “It gave me a different perspective on the people in the mental hospital, a sense that maybe they were not so crazy or as bad as the sterile environment they were living in.”

He wrote the first few pages of Cuckoo’s Nest on peyote. “It had little effect on the plot, but the mood, and particularly the voice in those first few pages, remained throughout the book... By the time I started taking peyote and LSD, I had already done a great deal of reading about mysticism — the Bhagavad Gita and Zen and Christian mystical texts. They helped me to interpret what I was seeing, to give it meaning.”

Kesey followed Cuckoo’s Nest with another bestseller, Sometimes A Great Notion (1964) and virtually abandoned novel writing for nearly three decades. He believed that the first rule — whether as a writer or a dancer or a fiddle player or a painter — is “don’t bore people.” He would quote his father who used to say that good writing was not necessarily good reading.

Kesey would also assert that the novel was a noble, classic form but it didn’t have the juice it used to. “If Shakespeare were alive today, he’d be writing soap opera, daytime TV, or experimenting with video. That’s where the audience is... Things you think you’re saying for the first time ever, have been said better before by Shakespeare, though they may need saying again.”

By the time he died on November 10, 2001, aged 66, Kesey had written two more novels, Sailor Song (1992), and Last Go Round: A Dime Western (1994), besides a few non-fiction works and children’s books. But if he is remembered to this day, it is primarily due to the Cuckoo’s Nest. As novelist Robert Stone eulogised, “If American Literature ever had a favourite son distilled from the native grain, it was Kesey.”