DH Illustration: Sajith Kumar

Faridabad resident Rakesh (name changed) took a family member for gall bladder surgery at a tony South Delhi hospital and was given an estimate of Rs 2.30 lakh. But at the time of discharge, the total invoice of Rs 3.90 lakh sent him reeling. When the bill was scrutinised, it was found that the patient had been separately billed for the removal of the gall bladder and for the removal of the adhesions around the organ, without which its extraction is not possible. The OT-charges, consumables, all had been billed twice over!

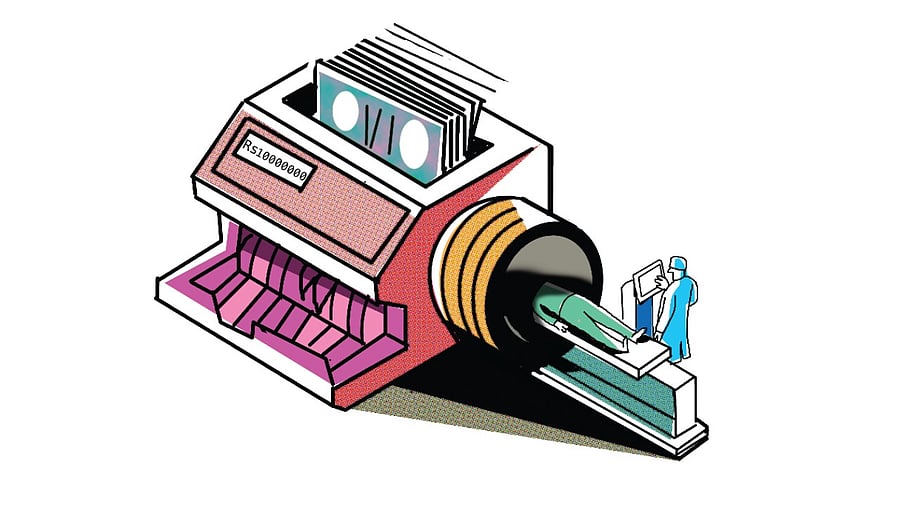

The arrival of a bill at a corporate hospital is no less scary than the disease and its diagnosis, and Rakesh was one among many Indians who have been through this shock. Yet, this extravagant side of Indian healthcare does not get as much policy attention as it deserves. For decades, the magic number in Indian healthcare has been 2.5 — the GDP percentage deemed ideal for India’s public healthcare spend. The 2025–26 Union Budget allocation for the ministries of health, AYUSH and other related ministries stood at 0.33% of GDP. This disparity set the context for healthcare conversations, which have traditionally been framed around deficiencies — resources, manpower, facilities. But there is another side to it: excesses — overtesting, overmedication, surgeries that may not be strictly essential, add-on procedures that inflate surgical expenses, equipment rentals that allow room for corporate profiteering — the list goes on.

From billboards to ICUs

If that sounds counterintuitive, think of the umpteen billboards you encounter every day advertising the latest technology and sophisticated medtech devices acquired by prominent hospital chains. These acquisitions are not for charity; these are investments hospitals make, and there is often an intention to extract returns from patients — who else? The entry, over the last couple of decades, of multinational investors into the Indian private hospital space bears testimony to how lucrative the sector is.

Much has happened in the last few years to cover ground on India’s goal of Universal Health Coverage (UHC), including the rollout and expansion of the Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana (PMJAY) in 2018, which promised an annual health cover of ₹Rs 5 lakh to all eligible families. A recent amendment has entitled people over 70 years of age, irrespective of financial background, to the same cover under PMJAY.

However, in the hands of unscrupulous private hospital owners, it has become yet another tool of overtreatment, widening the horizons of what in insurance parlance is known as moral hazard, beyond traditional procedures such as hysterectomies and Caesarean sections.

In one case in a city in western India, a hospital performed angioplasties on PMJAY patients even though they were not medically indicated. Some patients who underwent the procedure to remove blockages in blood vessels actually had zero blockage. The matter came to light after two people died. Moral hazard in insurance is defined as the propensity of an insured person to take more risks than necessary. In healthcare, it manifests as hospitals prescribing unnecessary tests and interventions to insured patients, thus depleting coverage without any material health gains. That this might be happening under PMJAY was flagged recently by BJP MP Darshan Singh Choudhary in the Lok Sabha. “Once a patient is admitted, his money vanishes, but full treatment does not happen,” he said, arguing for stricter norms in the scheme to counter the “monopoly of private hospitals”.

There may indeed be a need to scrutinise package utilisation under the scheme more closely. Acute febrile illness — in other words, fever — is among the top five packages claimed since the scheme’s inception in 2018. Hospitalisation for fever alone is not very common, particularly among uninsured patients. The excesses an admitted patient is subjected to can range from unnecessary tests to overpriced drugs and unindicated surgeries.

Refer-and-earn commissions?

Insured patients exhausting their coverage is one part of the conversation around excesses in healthcare. It becomes starker for patients who do not require hospitalisation because, except in rare cases, this expenditure is entirely out of pocket.

The biggest components of outpatient healthcare expenses are laboratory tests and medicines. The pricing dynamics of pathological tests contain a significant element of doctors’ commissions. This is problematic for two reasons. First, patients pay a markup so laboratories can recover this additional expense. Second, it hinges on the information asymmetry doctors possess — one of the reasons economist Kenneth Arrow argued against applying standard market economics to healthcare. If a doctor stands to benefit financially from each test prescribed, who oversees which tests are essential and which are driven by incentives?

Dr Arun Gadre, a gynaecologist and author, has spent a lifetime advocating ethical medicine. His book Dissenting Diagnosis, based on interviews with 78 doctors, lays bare the extent of corruption in healthcare. Speaking about excessive tests and why they cost so much, Dr Gadre says: “One pathologist told me that he would not survive if he did not give commissions to referring doctors. India allows medical technology without regulation or assessment of necessity. There is zero accountability for doctors and hospitals. Redress is left to patients through consumer courts, and that process is tedious.”

David Berger, an Australian primary care physician, spent time in India in 2012–13. He documented this practice of referral commissions in a scathing BMJ article, noting that all investigations attracted a 10–15% kickback to the referring doctor. While researching my book, a senior doctor who began his career in a government hospital in central Delhi recalled that, a couple of decades ago, young resident doctors earned nearly 33% of their monthly salaries from commissions from nearby pathology labs.

A veteran in the pathology business spoke of “small diaries” doctors maintain to track referrals for which labs owe them commissions. The amounts vary across cities and consultants, depending on patient volume and competition. The chain he now heads has built its diagnostic business on refusing to pay commissions and passing on the benefit to patients. As a result, its tests are significantly cheaper than those of competitors.

A case of more for more

Incentive dynamics are similar for drugs: more prescriptions mean higher costs. A study published last year in the Indian Journal of Medical Research by ICMR researchers found that the most common consequence of deviant prescriptions was increased cost, observed in 63% of prescriptions analysed. The implications go beyond cost — unnecessary medications can cause side effects, often requiring additional drugs to manage them. The Uniform Code for Pharmaceutical Marketing Practices prohibits pharmaceutical companies from offering gifts or travel incentives to doctors (with limited exceptions), yet the practice remains rampant. One company even approached the Supreme Court seeking income tax benefits for freebies given to doctors. Prescription audits are rare in India, leaving medical ethics as the only defence patients have against inflated out-of-pocket drug expenses.

One surgery too many

“Dar bikta hai (fear sells),” says Dr Gadre, summing up excesses in healthcare — from hysterectomies and cataract surgeries to angioplasties and Caesarean sections. He attributes this to weak ethics and the rise of profit-driven corporate healthcare. The root cause, he says, is the absence of enforceable regulations and protocols for prescribing tests, drugs and interventions. “Some individuals and hospitals practise ethical medicine; charitable hospitals do excellent work. But corporate hospitals thrive on excess. There are no incentives for ethical practice,” he adds.

Non-essential surgeries rising

Thousands of Indians wait for life-saving surgeries because they cannot afford private care. At AIIMS Delhi, waits can stretch to two years. Ironically, India also performs a large number of non-essential surgeries, with surgical births topping the list. Urban India has an alarmingly high Caesarean rate; nationally, it stands at 32%, according to NFHS-5. The public–private divide is stark: 49% of private-sector births are surgical, compared to 22% in government facilities.

State-wise variations are startling. In urban Tripura, 47.55% of births are C-sections — 95% in private and 40% in government hospitals. In urban Andhra Pradesh, the rate is 50% (66% private, 30% government), while in urban J&K it stands at 54%, with private facilities accounting for a worrying 91%. The WHO considers 25% the ideal rate for medically warranted C-sections.

India also sees excessive hysterectomies. NFHS data suggests over 3% of Indian women have undergone the procedure, two-thirds in private hospitals. The Supreme Court noted this in 2023, directing the government to ensure implementation of guidelines. A 2019 Thomson Reuters investigation found 66.8% hysterectomies in India were unnecessary, with 95% occurring in the private sector. NHA data shows 2% of PMJAY claims were for uterus removals, concentrated in six states.

Shrouded in opacity

Decisions on surgery are cloaked in opacity. Guidelines exist, but without statutory backing or monitoring, adherence is weak, leading to catastrophic healthcare costs. In a Tier-I corporate hospital, a laparoscopic hysterectomy can cost up to ₹ Rs 5 lakh, depending on bed type.

In a 2023 Indian Journal of Nephrology article, Dr Sanjay Nagral of Jaslok Hospital flagged that nearly 10% of organ transplants in India involved foreigners — high by global standards — almost exclusively in the private sector. This persists despite thousands of Indians awaiting transplants due to donor shortages. He notes that the tendency to overoperate is endemic across specialities.

“It is not difficult to see why private healthcare globally encourages more procedures. Unfortunately, this includes invasive surgeries with risks of complications. In India, perverse incentives, weak regulation, poor auditing and low patient awareness make it worse,” says Dr Nagral.

Opacity extends beyond clinical decisions into the operating theatre. In corporate setups, patients often cannot verify what procedures were actually performed. In surgeries like piles, only the surgeon knows how many growths were treated or which techniques were used. Multiple procedures may be billed under different justifications, leaving patients with no way to verify. The responsibility to protect patients lies with the state, ideally through a regulator empowered to act against errant doctors and hospitals.

This conversation on excesses must be addressed before India can realistically achieve universal healthcare. With private participation inevitable for a population of 1.4 billion, unchecked profiteering will drain public resources unless costs and protocols are rationalised.

The author is a journalist and public policy professional. Her second book, Games Hospitals Play (Bloomsbury 2025), deals with the brass tacks of healthcare inflation in the private sector. Views are personal.