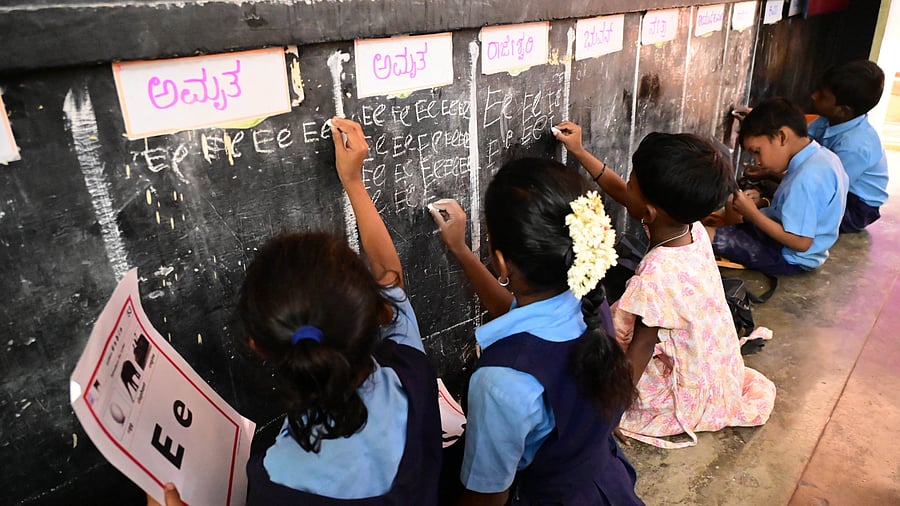

The percentage of Union government spending on education has hovered between 2.7% and 3.1% of the GDP for the past few years. In pic, students at a government school in Bengaluru.

Credit: DH Photo/B K Janardhan

Chennai: In 1966, the Kothari Commission, India to overhaul the education system, recommended that India spend 6 per cent of its GDP on education. This recommendation was later endorsed by authors of the National Education Policies of 1986 and 2020, under the Rajiv Gandhi and Narendra Modi governments respectively.

Decades have passed but these recommendations, reiterated by several commissions have remained only on paper. In practice, India’s percentage of GDP spent on education remains abysmally low at 2.7 per cent in 2023-24, as per the Economic Survey tabled in Parliament on July 22, 2024.

For the past several years, this percentage has been hovering between 2.7 per cent and 3.1 per cent. If one adds investments made by state governments, around 4 per cent of the GDP is spent towards education. Countries like the US (6 per cent) and the UK (4.2 per cent) make significantly higher budget allocations to education.

Allocations towards higher education and research and development, though crucial, also remain quite low at 0.69 per cent, even though the NEP 2020 proposed a budget equalling 2 per cent of the GDP.

Educationists and activists blame successive governments at the Centre for a failure to focus on education. They flag the lack of adequate funds for enhancing school infrastructure, failure to put in place ways and means to fill teaching vacancies and not enforcing compliance with the historic Right to Education (RTE) Act, as major issues.

The slow pace of utilisation of Union government funds by state governments is also a problem. A Parliamentary Standing Committee on Education in 2023 suggested a mechanism for faster utilisation. The committee noted that the tardy pace of submission of utilisation certificates by states contributed to a delay in releasing funds.

Bengaluru-based development educationist Niranjanaradhya V P puts how these low investments have impacted public education into perspective.

“The Kothari Commission said, ‘the destiny of the nation is being shaped in her classroom’ in 1966. On the contrary, we have neglected primary education since Independence, and it is taking a toll now.” Much of the funds released by the Centre and state governments are spent on meeting recurring expenses like teachers’ salaries, infrastructure repair and maintenance and construction. Despite this, an acute shortage of teachers across the country is observed, with many states resorting to the appointment of temporary staff.

As of March 2023, as many as 9.86 lakh posts remained vacant at the elementary, secondary, and higher secondary levels against the sanctioned strength of 62.71 lakh in the country. Of this, about 7.5 lakh vacancies are for teachers of classes one to eight, against the sanctioned strength of 48.10 lakh.

Even 15 years after education was made a fundamental right, the percentage of all elementary schools that are compliant with infrastructural norms under the RTE is a mere 25.5% across the country, calling for urgent action to bring more children into the system.

Another worry is the decline of enrolment in public schools by 47 lakh in 2023-24, when compared to the previous year, as revealed by the Union Education Ministry’s Unified District Information System for Education Plus (UDISE+) report for 2023-2024.

Higher education

The neglect is plain to see in higher education as well. Over 40% of teaching positions in public universities, including those run by state governments, remain vacant. Sparse allocations to research and development are also mostly concentrated towards premier engineering institutes at the state level and IITs at the national level, experts say.

As of 2023, nearly 14,042 teaching positions (34%) of the sanctioned strength in the Union Government-run higher education institutes, including IITs and IIMs, lay vacant.

Even four years after adopting the NEP, the Union government has not allotted enough funds for implementing recommendations, says E Balagurusamy, former vice-chancellor of Anna University, Chennai.

“We have plenty of universities and colleges, but our output is limited because we have not invested adequately in faculty and research. In the last 10 years, there has been no considerable increase in the Union Budget for higher education. Almost no research happens in a majority of state-funded universities across the country,” he says.

There is also a deficit in the number of patents filed by Indian universities when compared to other countries, he adds. Balagurusamy pitches for massive investments to improve the number of colleges and create more facilities and infrastructure.

“No Indian institute has found a place in the list of top 100 universities in the world. This shows that we have a long way to go,” Balagurusamy added.

The former Anna University V-C also said the government should pump more money into public universities so that they focus on research and innovation. “It is the government which has to spend money. We need to identify universities that can excel in research and fund them,” he said.

Although the Union government has laid much emphasis on the NEP 2020, it has split academicians and educationists. While proponents say it is among the most progressive policies, the opponents criticise it as an attempt to centralise education — a departure from how the Centre would merely propose a framework, allowing states to draft their policies in the past.

Many Opposition-ruled states have also expressed disapproval. Niranjanaradhya says though much stress is laid on the implementation of NEP, the intent of seeing the policy in practice is not reflected in actions. Especially in the allocation of financial resources to state governments under the RTE Act, the Centre’s neglect is plain.

For instance, in the 2024-25 budget, the amount allocated for states to implement the RTE Act has come down to Rs 37,500 crore.

“This amount is grossly inadequate. The Centre should fulfil its obligation by allotting adequate funds to implement the RTE Act, especially to enable schools to meet norms and standards. Education is a constitutional right. The Act clearly says the implementation is a joint responsibility of the Union and state governments. However, the Centre puts the onus on states, who do not have many resources,” he says.

National compliance with the RTE Act was 25.5% in 2021. A closer look at the figures reveals disparities at the regional, district, and taluk levels.

“We do not have fresh data on RTE compliance at the state level. The government is not transparent with such data only to avoid a debate on the effective implementation of the constitutional right,” Niranjanaradhya adds.

Spending on infrastructure, especially under the Act, is only undertaken when it is an absolute necessity, says Chennai-based activist Prince Gajendra Babu.

Improvements in these areas are difficult unless the government doubles the current expenditure in the next 10 years, as recommended by the Kasturirangan Report (Draft NEP 2019), says B S Rishikesh, who leads the Hub for Education, Law and Policy at Azim Premji University, Bengaluru.

“In the current allocation, a large percentage goes towards salaries. Though this varies from state to state, all spend the most on teacher salaries. This may be between 60% and 80% of their total education budget,” he says.

While state governments must raise the allocation for education, Rishikesh says, the onus is on the Centre to raise the bar year on year, as recommended in NEP 2020.

To make up for the cumulative deficiency since 1968, Babu, general secretary of the Tamil Nadu State Platform for Common School System, explains that the government spending on education should be at least 10% of the GDP.

Without increasing the spending, social development, which is directly connected with education, cannot be achieved, Babu adds.

Teacher shortages

To make up for the lack of permanent teachers, there is an increasing number of contractual teachers, which is against RTE norms. Teacher shortages are well beyond the RTE-mandated norm of 1:30 for primary and 1:35 for higher primary. States have been appointing ad-hoc teachers on a contract basis to fill the shortage, says Rishikesh.

“The biggest issue is that children do not get the support required to learn, with ad-hoc or temporary teachers, who are not even sure of their jobs. In this scenario, there can be very little support for students,” Rishikesh adds.

“The policy of contractual appointment is in contradiction with RTE. This too shows that we are not ready to spend money,” Niranjanaradhya adds.

The appointment of permanent teaching staff is essential for the continuity of academic education. “Ad-hoc teachers, who are paid very little, cannot be expected to display the same commitment as that of the permanent staff. Only permanent teachers can impart quality education, and we should move towards that if we are serious about primary schooling,” Babu says.

A close look at the government data reveals that teacher shortages are more critical for certain subjects, particularly mathematics and science, and in rural regions. “This tells us that recruitment has to be based on data, wherein teachers for appropriate subjects and regions are the ones selected,” Rishikesh says.

The Centre’s focus on opening special schools rather than spending on public schools that witness more enrolment is also an issue that many experts highlight.

The 2024-25 Budget earmarked Rs 6,050 crore to be spent on PM SHRI schools — a 116% increase from Rs 2,800 crore allotted in 2023-24.

Though PM SHRI identifies public schools and upgrades their infrastructure, not all schools can access the scheme as eligibility hinges on the complete implementation of NEP.

“Instead of opening more public schools, the Centre wants to score brownie points by launching schools with new names like PM SHRI. Their priorities are misplaced,” Babu says.

Niranjanaradhya also says that Rs 92,000 is spent on one child in a special school, whereas in a public school, Rs 50,000 is spent on each child.

“Why this state-sponsored discrimination and segregation? Shouldn’t all our schools have the same kind of facilities and quality teachers?” Niranjanaradhya asks.

Enrolment

Educationists also are sounding alarms over a decline in enrolment across preparatory (Class III to V), middle (Class VI to VIII), and secondary (IX to XII) levels, as noticed in the UDISE+ report. Bihar tops the list of dropouts at the preparatory level at 13.7%, Meghalaya (9.7%), Assam (6.8%), and Uttar Pradesh (5.4%).

Only four states — Tamil Nadu, Kerala, West Bengal and Telangana — have reported zero dropouts in both preparatory and middle levels, while Himachal Pradesh, Maharashtra, and UTs Chandigarh, Delhi, and Dadra and Nagar Haveli and Daman and Diu reported zero dropouts in preparatory level.

Arun Mehta, former professor at the National Institute of Educational Planning and Administration (NIEPA), says an analysis of the UDISE+ report reveals significant regional disparities in school infrastructure, with border and northeastern states experiencing the lack more.

“When viewed alongside enrolment and efficiency indicators, these changes in figures suggest the regional uneven effects of school closure, greater resilience in the government sector, and potential challenges for universal education goals. Therefore, they emphasise the need for region-specific interventions,” Mehta said.

Mehta added that the data clearly shows that the challenge of Out of School Children (OOSC) is not uniform across age groups as the percentage is higher among older children, which suggests retention is a critical issue.

The high number of OOSCs presents a significant challenge to achieving NEP 2020’s goal of universal school education by 2030.

“By implementing the suggested strategies, leveraging Samagra Shiksha, and continually analysing data, India can significantly progress toward providing quality education to all children. Addressing the reasons behind the high dropout rates, particularly in the older age groups, is paramount for the success of NEP 2020,” Mehta adds.

There is silence over the steep decline in enrolment nor is there an explanation nor is there an explanation for the declining number of schools covered under the survey or whether the decline is due to merging or closing down of schools, he adds.

The dropout rates indicate the quality of schooling on offer, says Rishikesh. Nearly 40% of children in India do not complete school education.

“The poorer the quality, the higher the dropout rate, as many research studies have pointed out. Whether it is dropping out at the elementary level or the secondary stage (grade 9 to 12), dropping out is a marker of the quality of school education in the country,” he adds.

“After education was made a fundamental right, even a single dropout is a gross violation of that fundamental right,” Niranjanaradhya says.

Babu accuses the Centre of pushing for the NEP 2020 and claims that the policy encourages private participation in public schools, which is not feasible.

However, Rishikesh argues otherwise, saying state governments that value progressive education are implementing various provisions even if they are not explicitly stating that NEP is being implemented. He argues that NEP 2020 does not promote PPP.