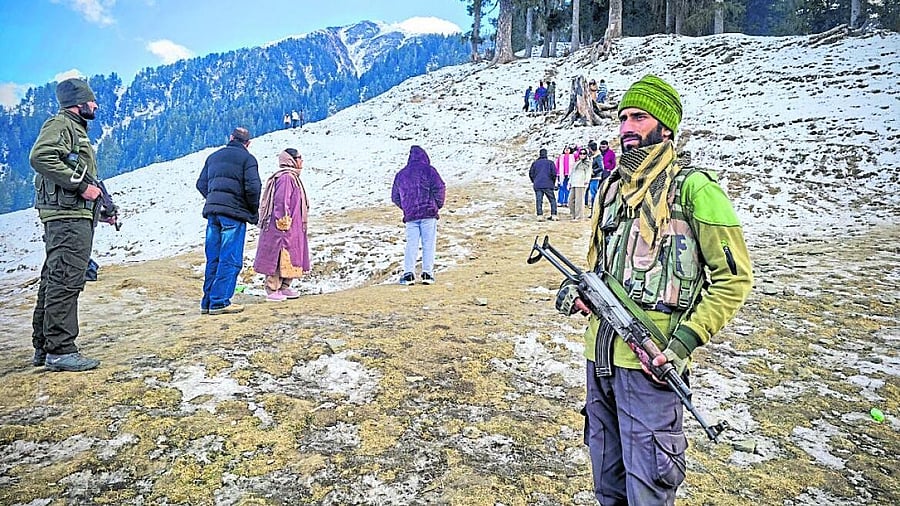

Armed Special Operations Group (SOG) personnel of the Jammu and Kashmir Police stand guard as tourists experience snow activities, at Guldanda in Bhaderwah.

Credit: PTI Photo

As winter tightened its grip across the Himalayas this January, an unsettling contradiction unfolded across northern India: Temperatures plunged sharply, yet snow — the lifeblood of the mountains — remained scarce.

From Kashmir’s plains to Uttarakhand’s high-altitude ridges, the familiar white blanket that defines Himalayan winters failed to arrive across large stretches, triggering concerns far beyond tourism or seasonal discomfort. Experts warn that shrinking snow cover is now reshaping water availability, livelihoods, and even regional geopolitics.

Heavy snowfall is traditionally routine in Kashmir — the heart of India’s western Himalayan hydrology — during “Chillai Kalan”, the harshest 40-day winter phase from December 21 to January 29. It insulates orchards, replenishes rivers, and sustains the Valley’s ecological and economic rhythm.

This winter, however, much of the Valley floor remained largely snow-free well into mid-January, even as night temperatures stayed below -6° Celsius. Higher reaches did receive snow, but the accumulation was light to moderate, and insufficient to offset the prolonged dryness below.

Meteorologists attributed the phenomenon to weak and infrequent western disturbances. Clear skies intensified nocturnal cooling but failed to deliver moisture, producing harsher cold without snowfall’s hydrological benefits.

Climate scientist Shakil Romshoo, one of Kashmir’s leading experts on Himalayan hydrology, has repeatedly cautioned that such winters are no longer aberrations. The region, he notes, is witnessing longer dry spells punctuated by short, intense weather events — a pattern consistent with climate change impacts. Reduced snowfall weakens snowpack buildup, with consequences unfolding months later — during spring and summer.

Trend, not exception

Long-term data reinforces the concern. Between 2003 and 2025, the Hindu Kush Himalayan (HKH) region experienced 13 below-normal-snow years. Alarmingly, four of the past five winters have recorded snow persistence below the historical average.

The winter of 2024-25 marked a critical low point. According to the latest assessment by the Kathmandu-based International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD), snow persistence across the HKH region fell to 23.6% below normal, the lowest level recorded in more than two decades.

Even snow-dominant basins were affected. The Indus basin, which sustains Kashmir and large parts of downstream Pakistan, recorded a 16% decline in snow persistence.

Seasonal snowmelt contributes roughly 23% of the total river runoff across the HKH region, with its importance increasing westward. For Kashmir, its absence or irregularity translates to increasingly erratic flows in the Jhelum and its tributaries — brief surges during early melt periods, followed by shortages when agriculture, drinking water systems, and hydropower projects need them the most.

Early indicators of stress are already emerging in Kashmir. Water and power-sector officials have flagged lower-than-usual winter flows in several streams and rivers, while hydropower generation has faced periodic constraints due to reduced discharge.

The absence of snow is especially worrying for orchardists. Winter tourism, another economic pillar, has also felt the impact. Gulmarg’s ski season has become increasingly dependent on short snowfall windows at higher elevations.

The pattern extends well beyond Kashmir. In Uttarakhand, an unusually prolonged dry spell has left even traditionally snow-laden landscapes largely bare this winter. Popular high-altitude destinations such as Tungnath and Om Parvat, usually cloaked in snow, had a barren look for much of the season.

According to the India Meteorological Department, dry weather persisted through much of early January, with rainfall forecast only in isolated pockets later in the month. The moisture deficit has begun to stress winter crops, such as wheat and mustard.

Uttarakhand Agriculture Minister Ganesh Joshi has directed officials to assess crop losses caused by the prolonged dry spell. Residents describe conditions as drought-like — a sharp departure from the dependable winter rains that sustained hill agriculture.

Geopolitical effect

The Himalayas feed river systems that sustain nearly 200 crore people across South Asia. As snowpacks shrink and melt patterns become erratic, water stress increasingly intersects with geopolitics.

In the western Himalayas, analysts warn that climate-driven hydrological variability could further strain India-Pakistan water relations under the Indus Waters Treaty (IWT). Signed in 1960, the treaty was framed around relatively stable flow assumptions, which climate change is steadily eroding.

Lower and less predictable summer flows in rivers such as the Jhelum and Chenab heighten downstream anxieties in Pakistan, particularly during dry years. Under such conditions, even treaty-compliant hydropower operations in Kashmir are viewed with suspicion, as reduced natural flows amplify perceptions of upstream control.

Experts caution that future tensions may be triggered less by new infrastructure and more by shrinking water availability. Environmental stress risks exacerbating the hardening of political faultlines in an already fragile region, particularly without climate-responsive mechanisms, improved real-time data sharing, and cooperative basin-level adaptation.

Adaptive responses — improved water storage, climate-sensitive hydropower planning, enhanced snow monitoring and cross-border data cooperation — are no longer optional. They are essential to prevent environmental stress from cascading into economic disruption and strategic instability.

(With inputs from Sumir Karmakar in Guwahati and Raju Gusain in Dehradun)