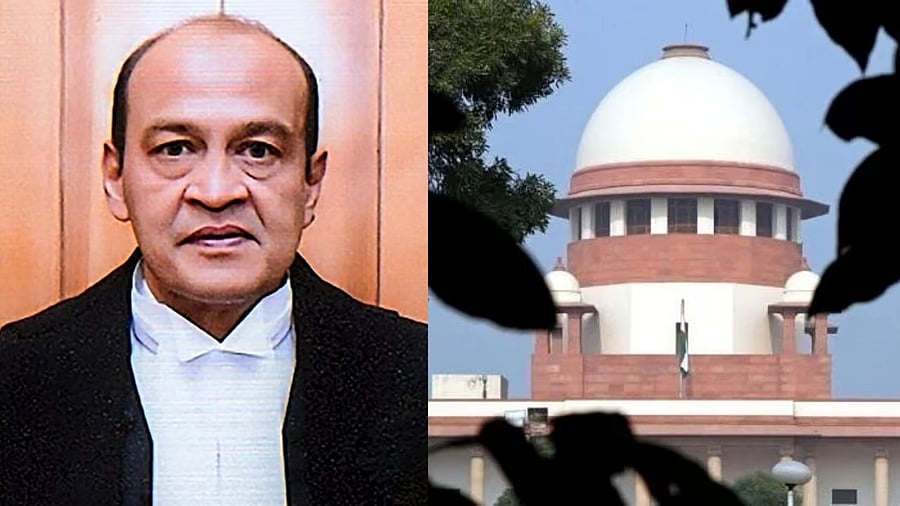

Photo of Justice Yashwant Varma, representative image of SC building

Credit: X@ANI/PTI File photo

New Delhi: The Supreme Court on Thursday said the in-house inquiry procedure on a complaint against a judge is fair and just, and it does not compromise judicial independence or contravenes the constitutional provisions related to his or her removal.

A bench of Justices Dipankar Datta and Augustine George Masih dismissed a plea filed by Justice Yashwant Varma, questioning the validity of actions initiated against him, including the recommendation for his removal, after having been indicted by an in-house inquiry committee report over discovery of cash haul at a store room of his official residence here during the fire incident on March 14, 2025.

"A judge by his conduct of being fair and just is supposed to earn for himself as well as the judiciary the trust and respect of the members of the bar as well as the litigants and all other stakeholders," the bench said.

The court pointed out, if a complaint of misconduct committed by a judge is received and if at an inquiry conducted under the procedure and the allegations against are found to have sufficient substance, he cannot claim any immunity - either by citing abrogation of fundamental rights or breach of the constitutional scheme for removal of a judge by initiating proceedings for impeachment that his conduct is not open to be commented upon by the committee or even by the Chief Justice of India.

Justice Varma, who was repatriated to Allahabad High Court without any judicial work, was indicted by a three-judge inquiry committee set up after the cash discovery. The then CJI had forwarded committee's report along with his recommendation to the President and the Prime Minister for removal proceedings.

Holding that the in-house procedure enjoyed legal sanctity and is not a parallel or extra constitutional mechanism, the court said Justice Varma's conduct during the proceedings did not inspire confidence as he participated in the in-house inquiry without any demur.

The “In-house Procedure” was devised by the Supreme Court in its full court meeting of December 15, 1999.

The court also held non-grant of hearing to the judge by then Chief Justice of India Sanjiv Khanna, prior to recommending his removal doesn't violate any procedure as such hearing cannot be claimed as a matter of right.

"The CJI has scrupulously followed the procedure which does not envisage a hearing to be given to the judge under probe after he has expressed his inability to resign or voluntarily retire. Even though a hearing ‘could have been given’, it cannot be equated with ‘should have been given’ in the absence of any such express obligation," the bench said.

The court also pointed out the nature of inquiry in the instant case was preliminary, ad-hoc and not final as well as not violative of any principle of natural justice.

The court, however, said, uploading of videos related to burning of cash placing incriminating evidence available against a judge under probe in the public domain is not a measure provided in the procedure, either expressly or by implication.

"But, then again, nothing really turns on the uploading of the photographs/video footage since the petitioner did not have any grievance in relation thereto which is obvious from his failure to question such uploading at an appropriate time thereby allowing a situation to grow where the court is faced with a fait accompli," the bench said.

In its 57-page judgement authored by Justice Datta, the court held the in-house inquiry or its report in itself does not lead to removal of a judge, unlike the constitutionally ordained procedure.

"The in-house inquiry is not a removal mechanism in the first place, much less an extra-constitutional mechanism," the court said.

The court also held the provision in the procedure requiring the CJI to write to the President and the Prime Minister along with the report of the committee to be quite in order, legal and valid.

"The office of the CJI is not to be regarded as a post office that the report should only be routed through him without his observations," it said.

The court also emphasised that it is unreasonable to even think that despite an incident of the present nature, the CJI would wait for the Parliament to take action.

"It is up to the Parliament whether or not to activate Article 124 (impeachment) of the Constitution. Left to him, the CJI upon being informed of a judge’s remissness does have the authority – moral, ethical and legal – to take such necessary action as is warranted to keep institutional integrity intact," the bench said.

The court also said if indeed any fault were found in the procedure and questions were to be raised, Justice Varma ought not to have waited for completion of the fact finding inquiry set in motion by the CJI.

"The conduct of the petitioner, therefore, does not inspire much confidence for us to entertain the writ petition," the court said.

With regard to the in-house procedure, the bench said it acts as a check on judges’ unbridled freedom of action and thereby seeks to prevent outcomes that could be harmful or unjust.

"It must be remembered that not all misbehaviour of judges necessarily rise to the level of "proved misbehaviour" attracting Articles 217 and 218 read with clauses (4) and (5) of Article 124," the bench said.

To address the growing concern of incidents of misconduct, the court pointed out, the procedure has been craftily designed to discipline juddges internally for such misconduct that is sufficient to tarnish the dignity of his office as well as the institution to which he belongs.

"No Judge, either of the Supreme Court or the High Courts, being above the law, acting in the discharge of his judicial or administrative/non-judicial or official duties in a manner attracting a possible complaint of not abiding by the Restatement of Values of Judicial Life (widely regarded now as the Code of Conduct for Judges of the Supreme Court and the High Courts) has to be shunned," the bench said.