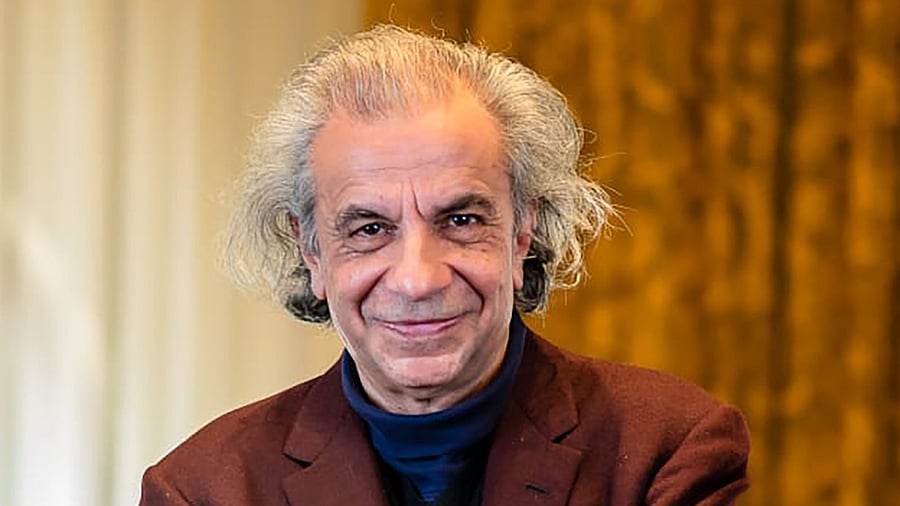

Akeel Bilgrami.

While secularism refers to the separation of religion and State, debates have persisted about how it differs from religious pluralism. Akeel Bilgrami delves into the genesis of secularism, different ideological strands in the Indian freedom movement, and the roots of contemporary Hindutva nationalism. Excerpts.

You’re here as a part of the jury for the Infosys prize. Could you tell us something about that?

This is an annual prize in six different areas, and I am on the jury for the humanities and social sciences. I think it’s very worthwhile, partly because the winner then has to spend a month of sabbatical lecturing in educational institutions in India. Anything promoting intellectual exchange is great.

Can you explain the historic and material conditions in which Western secularism arose?

Western secularism arose because of certain consequences of European nationalism. For centuries, state power was justified as the monarch’s divine right. But the rise of modern science in the 17th century undermined this justification, leading to the emergence of the entity of the nation. The nation-state became fused, where a feeling for the nation was created to justify the state. A century later, this began to be called nationalism. This national feeling was created by finding an external enemy inside the territory — Protestants in Catholic countries, vice versa, etc. With emerging statistical forms, concepts of majority and minority emerged, and this subjugation was called majoritarianism. This caused backlash by minorities, resulting in civil strife. Secularism emerged to repair the damage, where it was decided to keep out religion from polity.

You have referred to Nehru’s The Discovery of India and pointed out that there was an “unself-conscious pluralism” across the centuries in India. What does it mean?

By unconscious pluralism, I am referring to people living side by side, which is undermined by nationalism, as in Europe. When you choose a particular group to despise, you generate the ‘other’. But there is no other when people (Hindus and Muslims) worship in the same Dargahs. The Discovery of India is very close to Gandhi’s thinking. But there were differences between Gandhi and Nehru too regarding their vision for independent India.

Why do you think the genesis of today’s Hindutva nationalism started around the Emergency (1975-77)?

Many feel the roots of this sort of Hindu nationalism started in the 1920s, if not earlier. The Congress had quite a strong (Hindu) Mahasabhaite element. I believe, in these matters, you need a distinction between two notions: the roots and antecedents. These were antecedents, which means they’re probably unresolved questions. But I don’t believe the roots set in until the 70s and 80s.

Can you elaborate?

Firstly, the Hindu Right showed a lot of courage and resisted the Emergency. In fact, they showed more courage than the Centre Left, who laid down like doormats and allowed Indira Gandhi and her son Sanjay to just step on the nation’s liberty. As a result, they got electoral respectability and a moral high ground which they never had before. Secondly, post-emergency, especially in the 80s, there was a kind of democratisation, absent in Nehruvian times, where castes with no power began to get some rights. That exposed how deeply divided Hindu society was by caste. The Hindu right confronted this in the standard European way — found an external enemy within (Musalman) to despise and subjugate. It was a very determined concerted effort on the political field and cultural field. Those are the roots.

During the freedom struggle, while Gandhi, Nehru and some revolutionaries emphasised communal harmony, the RSS stood by its core positions like Hindu Rashtra...

All sorts of things were there. There was the left, the Hindu right and the Ambedkarite strand. But the Gandhi-Nehru strand was undeniably the major one. Ranadive (CPI leader) said it’s a miracle that the communists survived and weren’t just swallowed up by the Gandhi Congress.

MS Golwalkar (RSS leader) once said, “Those who declared no Swaraj without Hindu–Muslim unity have perpetrated the greatest treason on our society.” The fundamentals haven’t changed.

Certainly they were saying things like that, but they were antecedents. Now, they are not only saying that but also implementing it. What fuels your case more is that RSS was setting up grassroots. But those who were part of the grassroots were also swept away by the freedom struggle, and there may have been ambivalence in people’s minds. Something really took place in the emergency period and the decade after which led to the current developments.

Did the end of a generation by the mid- or late 1960s weaken the secular, democratic credentials of the national leadership?

Yes. When roots begin to flower, it’s not restricted to the Hindu right. They set the agenda, and even those with a secular legacy (get influenced). You mentioned Nehru, but Gandhi was fiercely, deeply against the Hindu right. In fact, the Hindu Right killed him. They saw him as a threat because he had a different vision of Hinduism. Nehru stressed class and thought this would go away, but that didn’t happen at all. Gandhi had a more realistic sense of Hinduism’s non-Brahminical tradition.

As an academic, how do you look at textbook revisions in India, where topics like the Mughals, the Babri Masjid demolition and the post-Godhra riots have faded mentions?

It’s a brazen form of undermining academic freedom. It also happened in Pakistan, and we are really becoming like Pakistan and Europe. Gandhi said we never had that damage and wondered why we should mimic Europe. But the very same reason why he wasn’t a secularist is a reason to be a secularist now. Because we are now mimicking Europe.

How do you see the denial of bail to Umar Khalid and Sharjeel Imam?

Criticising the government is anti-national? It just doesn’t happen unless you’ve really gone completely authoritarian in the way that McCarthy was. I think it’s very important for people in the media, etc., to fight for the freedom of information. You need some agency to call out corruption. UPA 2 fell because people were able to call out corruption, and this government is as corrupt as UPA 2, if not more. If you can’t call out corruption, a real sense of people’s sovereignty gets eliminated.