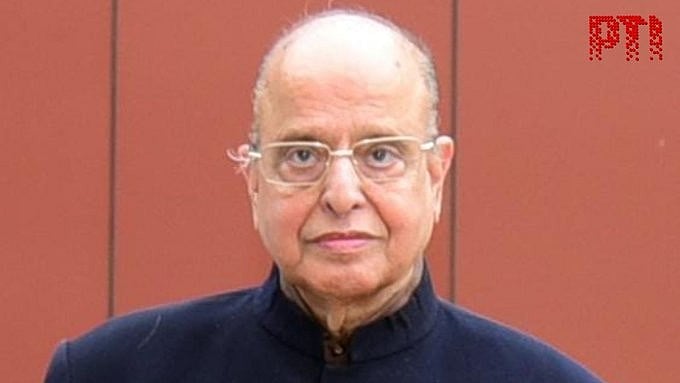

K Kasturirangan.

Credit: X/@PTI_News

New Delhi: A year after Pokhran-II, when Krishnaswamy Kasturirangan was delivering the first National Technology Day lecture in Delhi, he slipped in a few slides towards the end of his presentation. For the first time, the world came to know about ISRO’s outer space dream.

The former chairman of the Indian Space Research Organisation, who passed away in Bengaluru on Friday, will always be remembered for taking the space agency to the uncharted territory of interplanetary missions, without compromising its core tasks related to economic development.

Those slides carried early work from ISRO scientists and engineers on how the PSLV and GSLV could be used to reach the Moon, Mars and Venus. The idea received endorsements from policy makers and the scientific community, leading to the government’s approval of the Chandrayaan-1 mission in 2003 within a few months of his retirement.

He played a key role to rope in scientists from NASA and Brown University, USA to make crucial payloads for the mission – including the one that would later found water molecules on the lunar surface. When India’s first moon mission blasted-off in October 2008, his shadow was all over it.

As a young scientist he was involved in building the first generation Rohini and Bhaskara satellites and later in the nine years he helmed the ISRO, Kasturirangan oversaw a series of successful launched and operationalisation of the Polar Satellite Launch Vehicle – the current workhorse for Indian space programme - and the maiden flight of the Geosynchronous Satellite Launch Vehicle (GSLV) to carry heavier satellites to higher altitudes.

In fact, the GSLV had a disappointing start as the first flight had to be aborted just four seconds before the launch due to a technical glitch. But the space agency under his leadership bounced back within a month to register the successful launch in April 2001.

“It was the longest 60 minutes of my life,” he said later in the post-launch press conference once the GSLV put a satellite in orbit.

The affable scientist who counted Vikram Sarabhai and Satish Dhawan as his mentors later served as a nominated member of the Rajya Sabha for five years; chaired a panel on the protection of the Western Ghats and was the architect of the National Education Policy that envisages a new education structure and 100% gross enrolment by 2030.

He was also an advisor in the Planning Commission besides heading various government panels and being a part of the governing councils of many academic institutes. For his ISRO colleagues, he was a sounding board who would patiently listen to all new ideas.

The years he spent in the Parliament coincided with debates on the Indo-US nuclear deal. As a nominated member and a respected scientist he would often explain to the members how the deal – opposed by the BJP and Left parties – would not only benefit India’s nuclear programme but also open up doors for other critical technologies.

Years before Indian armed forces opened up on the military use of space, Kasturirangan spoke about the importance of having a space command. “I would like to make a statement regarding a closer examination of the role of the space system in national defence... What kind of an integrated space command we need to establish in the coming years,” he said in the RS in March 2008.

He also argued about having a “new space policy” a “space act” and sending Indian astronauts to space with long-term scientific goals.

It is ironic that Kasturirangan moved on to the other side just weeks before the second Indian astronaut would take off for the International Space Station.