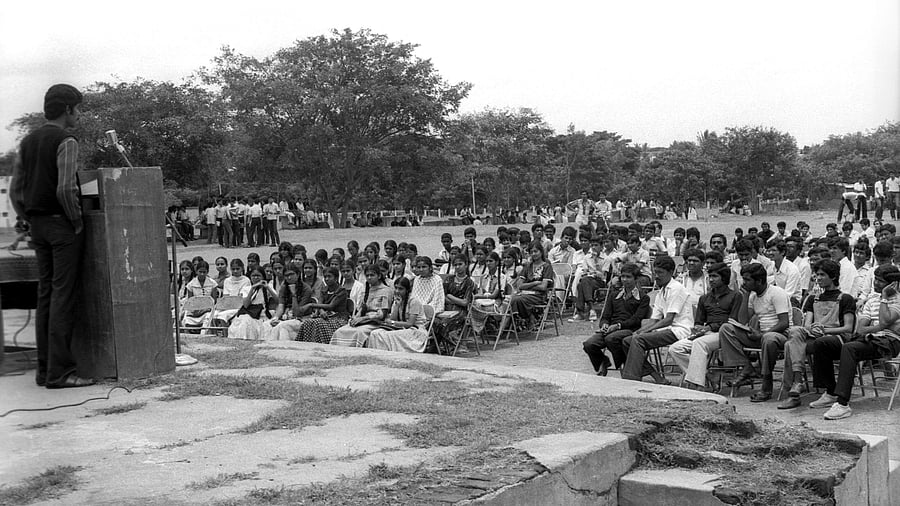

A file photo of a student election campaign at National College, Jayanagar, in1983.

Credit: DH Archives

Batting for the return of campus politics, former student leaders from Bengaluru say election days felt like a festival — with hand-painted banners declaring the names of candidates and their qualities stuck around the campus, and winners later doing a round of thank-yous in clasrooms. Unlike today’s restrictive campus climate, they say there was no fear of expulsion or hesitation to speak up for one’s rights.

Chief Minister Siddaramaiah is considering a proposal by the National Students’ Union of India (NSUI) to revive student elections in Karnataka. The ban was reportedly imposed in 1989 by the Veerendra Patil-led Congress government after incidents of violence during campus polls. But a few colleges continued to have elections through student bodies.

Former student leaders say the absence of campus politics has left students apolitical and unaware of their rights. It should return democratically, with rowdyism and political interference kept in check, they add.

Attendance shortage

K R Ashok Kumar served three consecutive terms as student union president at National College Basavanagudi (1983-86). He credits his freedom fighter father and admiration for Atal Bihari Vajpayee for shaping his political instincts. His syndicate (a group of candidates) worked to improve campus safety, expand library access and boost faculty support for disadvantaged students, and clarify scholarship information. In one case, nearly 300 students risked missing final-year exams due to a 5-10% attendance shortage. He argued they had good academic records. After rounds of talks with the principal and heads of departments, the issue was resolved in the students’ favour. The activism extended beyond campus. After the N Gangaram building collapse in 1983 killed 123 and left 120 injured, his union mobilised students and raised nearly Rs 1 lakh, which they handed to the chief minister’s office. Though Kumar was approached to join politics, he opted for a career in physical education.

In 1992, Shobha S became general secretary at Government PU Girls College, Malleswaram, and later held the same post and presidency at Maharani Arts College for Women, opposite Freedom Park. At the latter, “the student union room stayed open from 9 am to 4.35 pm” for students to voice concerns. She organised inter-class competitions and a film festival, and encouraged participation in citywide conferences on issues like communal harmony, acid attacks, and female foeticide. Today, she is an activist with the All India Mahila Sanskritik Sangathan. “My student union days made me politically aware and emboldened me as a woman,” she says.

Crimes against women

Rama T C followed in the footsteps of her seniors at Maharani Arts College for Women, inspired by how they visited classrooms to hear student grievances and promise action. She contested for president in 1995, in what she says was the first election with Electronic Voting Machines (EVMs) instead of paper ballots. Her syndicate lost amid suspicions of rigging, prompting a strike and consultations with public intellectuals. A re-election was held, and Rama won.

Even earlier, as general secretary, she led protests against a molestation incident. The agitation led to the arrest of the accused and campus reforms like CCTV installation, enhanced security, and an STD booth. The dowry killing of an alumna in Goa also spurred student protests around K R Circle, drawing thousands. “Her sister, who studied with us, came to the union. She said her sister was missing, and around the same time, a Kannadiga woman had been found dead in Goa. Our senior Uma Devi led the protests. They demanded the culprit’s arrest within a week — her husband was jailed in three days,” says Rama, now an activist with All India United Trade Union Centre.

Campus activism has long been a launchpad for politics, and Saleem Ahmed is one example. He began as student union president at Sheshadripuram College in 1982, rose through NSUI ranks to head its Karnataka unit, and now serves as chief whip in the Legislative Council. With no political background, he says student elections jumpstarted his career. He recalls taking up issues like bus fare hikes and admission delays, and calling strikes when talks failed. Only 1% of the student union scene was marred by violence and outside interference, he claims.

V N Rajashekhar, former all-India president of the All India Democratic Students’ Organisation, says Bengaluru youth fought on a range of issues — from rising dosa and coffee prices to opposing college donation fees and joining the protests against the 1996 Miss World pageant in the city. Rajashekhar did not start out in student politics at college, but in school when was studying in Class 8. "The first time I participated in a protest was during the emergency years," recalls the 57-year-old, who's now part of the Save Education Committee. Unlike the popular belief that student activists were not academically inclined, he says many from his time were rank students.