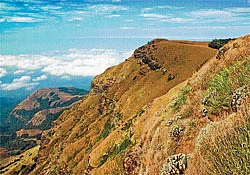

The long range of mountains in the western coast of Karnataka is an important geographical feature of the State. A major portion of the Western Ghats, distributed over six states of peninsular India, stretches across the coastal belt like a protective barrier. In addition, these lofty hills also break the annual monsoon from the south-west to ensure copious rainfall. The Western Ghats are endowed with a perennial river system and a fair distribution of tropical evergreen forests apart from diversity of wildlife. The varied topography of abrupt drops and deep valleys on the western side, grasslands of rolling hills and a labyrinth of shola forests at higher altitudes have compartmentalised diverse and distinct ecosystems.

The off-shoot of this relentless process is not only a high degree of endemism, i.e, the presence of certain species of plants and animals only in these parts, but also the evolution of newer, yet-to-be-identified varieties of life forms.

Blessed with such a rich biodiversity, it is little wonder that the Western Ghats are listed as the only other biodiversity hotspot of India after the Eastern Himalayas. Kudremukh, a towering range of hills, occupies the central region of the ghats with many tall peaks, the tallest of them touching 6,214 ft. The hill range gets its name from the shape of its peak (like a horse’s face). Thanks to its unique appearance, ancient mariners used it as a landmark to navigate.

It was during the British era that the first attempts were made to reclaim parts of the Kudremukh range for plantations of tea and coffee.

But later on, in 1916, keeping in mind the rich biotic attributes of the area, they declared it a reserve forest to limit the impact of cultivation. The tracts of Kudremukh, being a storehouse of ores, chiefly iron ore, prompted Kudremukh Iron Ore Co. Ltd ( KIOCL) to start a factory to extract the same.

However, constant and widespread campaigns by environmentalists to ban ore extraction so as not to disturb the fragile forest bore fruit when the Supreme Court clamped a ban on the company’s mining operations in 2005.

This, coupled with the fact that Kudremukh was declared a national park as early as 1987, provided a thrust to biodiversity conservation efforts.

Trekking haven

Kudremukh National Park, extending over 600 sq km, is not just a biodiversity hotspot, but also has varied landscapes including hills, valleys and forests. For avid trekkers, it is the most sought-after destination. There are 13 different trekking routes of varying levels of difficulty, crisscrossing the ranges. Decades ago, groups of trekkers were known to scale the mountains regularly from different routes. After Kudremukh was declared a national park, some restrictions on free movement became necessary.

To take up a day’s trek would require due permission from the Forest Department accompanied by their staff.

With the decks being cleared for the Kudremukh National Park to be made a tiger reserve, trekking here might soon be a thing of the past. So, on a trek to the region for one last time, this writer chose the only approach route that was allowed.

Arriving at Samse (a sleepy town near Kalasa in Chikmagalur district) by morning, we walked up the moderate slopes crossing the bridge on a stream to reach the house of Rajappa, who has been organising the permissions, food and stay for trekkers. This spot is called Mullodi, a charming spot with gurgling waters of Somavathi Falls in the vicinity.

Our trek began post-breakfast. The initial slopes were steep and hard to trek until we reached a resting point under the shade of a lone tree.

The rest of the trail went up gradually along a gorge on our right as we glimpsed the first view of the peak. Higher up, the landscape became plain and even, dominated by grasslands. The folds of green rolling hills devoid of tree cover contrasted with frequent patches of sholas so common in the Kudremukh region. Half way through, we rested again at a ruined house. This was where Simon Lobo, a grand old man who lived here decades ago, is said to have offered shelter to tired trekkers. After his death, his sons and family members abandoned the place.

With restrictions on the entry of visitors to the National Park, the movement of wild animals seems to have become unhindered as we could spot sambhars every now and then.

At the top are remains of an old church built during the British period. It has some interesting murals which are fading with time. The stream flowing through the deep jungles is cool and rejuvenating.

A half-an-hour’s hike further took us to the summit where there were high-velocity winds. The views from here of the valley with cumulous clouds far below are stunning.

The retreat to the camp was easy and quick, even as we we realised that this could well be our last trek to Kudremukh. Declaring the National Park a tiger reserve is a positive step to ensure that the endangered tiger and its habitat thrives.