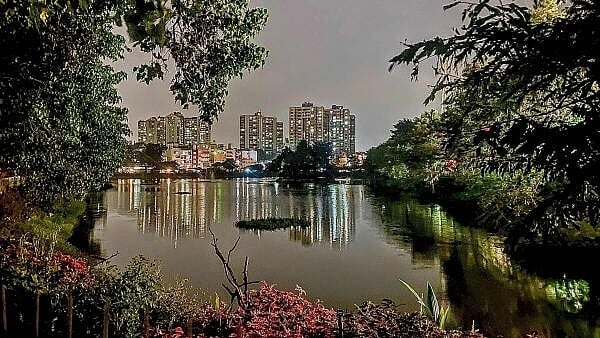

Puttenahalli lake

Credit: DH Photo

Bengaluru: The Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike recently served a notice to the Puttenahalli Neighbourhood Lake Improvement Trust, instructing them to cease maintenance of the Puttenahalli lake premises in the J P Nagar area.

This is just the tip of the iceberg—the question of who must care for our commons, such as lakes and parks, lies beneath the surface. The thin line between what is public and private is also called into question.

The Karnataka High Court, in a public interest litigation filed in 2008 over the rapid degradation, encroachment and privatisation of Bengaluru’s lakes and open spaces filed by the city-based Environment Support Group, commissioned the N K Patil Committee Report.

The report submitted in 2011 became a landmark guideline for preserving lakes. It emphasised the critical role of citizen participation in the planning and maintenance of urban infrastructure, especially concerning lakes and open spaces, and advocated for institutionalising community involvement through ward committees, lake protection committees, and partnerships with Resident Welfare Associations (RWAs) and civil society groups.

The Karnataka High Court accepted the Patil Committee’s recommendations in April 2012, directing the state to establish a state‑level Apex Committee and district‑level Lake Protection Committees, allocate funds, and apply the report’s guidelines across roughly 38,000 lakes statewide.

The Bengaluru region took the lead, with many lake enthusiasts being active. Many lake groups were established as part of this initiative. However, the momentum fizzled out when it came to formalising the civic engagement. Only about 12-13 groups signed the memoranda of understanding (MoU) with the BBMP for maintaining a few lakes. BBMP is the custodian of all the lakes, but citizen-led NGOs signing formal MoUs with the BBMP acted as caretakers, while also maintaining the lakes.

When BBMP cited a fund crunch as a reason for not fixing infrastructure, such groups collected funds from corporates or local donations to get things done. Puttenahalli Lake was one such lake maintained by the PNLIT, a citizen-led organisation formed in June 2010. The Trust signed an MoU in 2017 and worked towards filling the dry lake with water by liaising with the local community, getting treated water to the lake and maintaining it. However, the MoU with the BBMP expired in 2020, and the Trust was no longer authorised to take care of the lake.

“We still looked after the lake and flagged issues. Now we feel devastated because we have spent time, money and other resources on the lake, and we can’t see it going back to its old status because there is no one to follow up on the problems,” says Usha Rajagopalan, founder of PNLIT.

Why the problem?

This is the same for all citizen groups working on lakes — no MoU has been renewed since 2020. At the heart of the issue is another court order issued in March 2020. The legality of the agreements with “private/corporate” entities was called into question in a case on the privatisation of public spaces.

On March 4, 2020, the Karnataka High Court issued an order on the use of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) funds for lake maintenance in Bengaluru. The court emphasised that while the state and civic bodies could accept CSR contributions from private and corporate entities for lake rejuvenation, they cannot sign over control of lakes through MoUs that effectively privatise these resources.

It said: “Unless the legality of such agreements is examined, we cannot permit the State Government to execute such agreements. Therefore, we direct that till further orders are passed, the State Government shall not execute any such MOU with any Corporate Entity. However, this order will not prevent the State Government from taking funds from the Corporate Entities for the rejuvenation of lakes.”

This ruling allows CSR funding to support lake upkeep but draws a firm line: CSR is permitted — privatisation is not. It ensures environmental stewardship remains with public authorities under court oversight.

Lake volunteers say the BBMP appears to have misinterpreted this ruling and has effectively boxed all citizen-led groups into “private/corporate” bodies.

“Lake groups are citizen-led and have a stake in the lake. We are the immediate affected and beneficiaries of the lake,” says V Ram Prasad, founder of the Friends of Lakes group.

“The BBMP has made a mistake in misidentifying us and boxing us with professional NGOs whose business is to take CSR funds and save lakes. PNLIT, Mahadevpura Parisara Samrakshane Mattu Abhivrudhi Samiti (MAPSAS) and other lake groups are citizen-led and not corporate bodies. The BBMP must make this differentiation,” he argues.

New policy for CSR money

Sources say BBMP officials are unhappy about lake groups reportedly accepting CSR funds for lake maintenance. “Do they show accounts publicly on how much money was used for what? There is no transparency,” commented a source.

If this is the case, why can’t the BBMP accept funds from willing corporates for rejuvenation works itself, since the court permits it anyway?

One reason, volunteers say, is that corporates do not trust BBMP with the utilisation of money due to red tape and bureaucratic hurdles, while CSR goals have outcome mandates. Another reason is the lack of a proper and final policy by the BBMP regarding the acceptance of funds by private parties.

The draft BBMP Community Involvement for Lake Conservation (CILC) Policy, 2024, has been submitted to the court; however, acceptance is pending as the case itself is pending in the court.

The policy is a formal framework designed to enable corporations, citizen groups, NGOs, and other stakeholders to contribute legally to the development and maintenance of lakes in Bengaluru through CSR funding or voluntary efforts, under the BBMP’s custody. It mandates that such contributions align with the BBMP Act, 2020, and the Karnataka Tank Conservation and Development Authority (KTCDA) Act, 2014.

All contributions (assets, services, or funds) must be pre-approved by BBMP, follow detailed project submissions, and culminate in a formal MoU—ensuring BBMP retains ownership and public access. The policy prohibits the privatisation or commercial control of lakes and outlines clear terms for oversight, accounting, termination for violations, and legal liability. It aims to maintain transparency, prevent misuse, and ensure lake rejuvenation efforts remain accountable and in the public interest.

It effectively prohibits any citizen group or private body from accepting CSR funds to rejuvenate lakes and routes all money through the BBMP. Now, with the BBMP transitioning to GBA and the possibility of multiple corporations, the policy will need to change accordingly, leading to further delays.

Meanwhile, citizen groups want to be active participants in maintaining lakes. Volunteers say they will apporach the subject legally, through groups like the Federation of Bengaluru Lakes and individual lake groups.