Food label with ingredients

DH Photo/B H Shivakumar

I want to find some donkey milk for the baby, it seems it makes the baby healthy and stronger!”

I was at my wits’ end when a friend said this to me during my visit to see her newborn. Supposedly a tradition in Bengaluru, I could not imagine what the milk of a care–deprived donkey that feeds on roadside garbage and gutter water would do to her baby. The one-month-old had just recovered from a bout of diarrhoea. And to think that her postgraduate degree did not deter her from following an unscientific belief that defied all logic!

It is possible to dismiss this as a one-off behaviour stemming from the blind beliefs that still dominate our food culture. But are we sure all the food we stuff our faces with is safe enough? What about the deep-fried bondas and bajjis, or those French fries we pop in, sometimes even when we are well aware of what saturated fat can do to us?

“Aham annam” — We are what we eat, a saying in Sanskrit goes. Data tells us that foodborne illnesses affect approximately 600 million people globally each year, leading to 420,000 deaths, with children, the elderly, the malnourished, and the sick being the most vulnerable. In India, nearly 100 million are affected each year by such illnesses and deaths number 120,000. Food safety in the country faces major hurdles — adulteration, pesticide overuse, unhygienic handling and weak enforcement. Lack of adequate storage facilities, fragmented supply chains and low consumer awareness deepen the crisis, making access to safe food a matter of privilege and luck, not policy.

Recently, a few young researchers, aged 15 to 18, shared with me a study they had conducted in which they found acrylamide in French fries and Paneer tikka. Acrylamide is formed when a starchy item is fried, roasted or grilled above 120 degrees, where ammonia in any of the items reacts with starch due to the Maillard reaction — the same reaction that releases aromas when spices are heated in oil or alcohol.

How many of us know what acrylamide is?

“Acrylamide is a known carcinogen; however, the percentage of it in food matters. Sometimes, the quantity is so small that nothing can happen even if you consume it for 50 years. Foods high in acrylamide should not be consumed often. Still, once in a while, it is not a big issue,” says Dr Bhaskar Narayan, Director of CSIR-Indian Institute of Toxicology Research. Other experts feel that French fries are more problematic — they advise avoiding heavily browned fries and eating light golden fries, not more than once a week. Because 100 grams of French fries can contain 150–500 µg of acrylamide, which can be 5 to 50 times higher than the safe limit of acrylamide that our bodies can tolerate.

Laced with pesticides?

Pesticides in food are a major cause for concern. Narayan explains that persistent organic pollutants (POPs), a well-known group of now-banned pesticides, were heavily used in the past. Since they do not degrade easily, even today, their traces can be found in the food grown in those soils. However, the quantity is not enough to be dangerous for human consumption in most cases. His advice: Most of the current pesticides on vegetables can be removed with a thorough wash. So always wash your veggies before cutting.

Alarming reports of milk contaminated with pesticides, heavy metals, or urea occasionally hit the headlines, along with stories of adulteration and unhygienic practices. How safe are the dairy products we consume?

P A Shankar, former director of Dairy Science College, Bengaluru, who is also a food safety expert, feels there is not much to worry about, as checks and balances are in place among major dairy sector players. “When we were children, there was a shortage of milk; it used to be rationed and sold through coupons. Today, we have enough milk production. Buy only branded milk products, because checks and balances are in place. The milk you buy should be pasteurised, and buying directly from dairy farmers is banned across India, to ensure food safety.”

He adds that no farmer knowingly feeds pesticide-infested water to the cattle. It all has to do with our practices. Pesticide residues from farming enter the water bodies. Similarly, contaminated water from industrial areas can also seep into water bodies or groundwater, which then reaches the cattle.

He says there are guidelines on the quantity and timing of the pesticide to be used, as well as procedures to be followed, which are sometimes flouted, leading to problems. “If farmers can be more mindful of what they use and how much they use, a lot of harm can be avoided,” he adds.

Is organic really organic?

Anything related to pesticides brings us to the question of organic food: Is organic food really organic? Who is testing? Who is ensuring the quality?

Most buyers rely on personal trust for organic food, as actual certification is practically impossible for direct, door-delivered vegetables and farm produce from farming collectives. Branded organic food is available in stores, which costs a premium. However, the pollutants already present in the soil may still affect the produce, even if no fresh pesticides are used, says an expert.

When it comes to organic, even the land has to be certified, and a three-year gap needs to be given before growing anything on it. The farm produce grown has to be registered for traceability. The processing units, such as mills, have to be registered too to avoid contamination with non-organic products. There are processes in place to ensure no mixing of products. There are also trading licences for organic products for those who want to sell the products without involvement in their production. The system is robust, according to Somesh, CEO of an organic wholesaler company.

However, like every other rule, there is a loophole here as well. There is no rule that every organic product needs to be certified, because there are small farmers growing many produce in their own ways and methods, with no uniformity. This is being taken advantage of sometimes by some elements. The items sold as “organic” need not be organic, and a normal consumer will find it difficult to differentiate without traceability, he adds.

Storage woes abound

The recent raid at Zepto’s Mumbai storage facility has raised questions about the storage of branded food and beverages, including wholesale storage and that of products belonging to instant delivery businesses.

“Unorganised labour, attrition, floating population, lack of training, and infrastructure for food safety are the elements that cause such problems. Strict in-house compliance and supervision by the government linked to the licensing of food storage facilities is a must,” explains Dr Shashikanth, former food safety and quality consultant for CII-FACE (Food and Agriculture Centre of Excellence).

The problem can also be at the manufacturing level when it comes to processed food. Even a panipuri vendor who prepares puris at home is a manufacturer.

“The main challenge for small manufacturers is ensuring the manufactured food is stored without cross-contamination. In a fully automated production line, the food product gets packed as soon as it is manufactured. However, in a semi-automated system, manual intervention is still required, and the process may not be entirely seamless. So the food might get spoiled, get contaminated, might get exposed to varied moisture levels,” says Bindu Jayaram, a food entrepreneur.

All manufacturers and supervisors must have FoSTaC (Food Safety Training and Certification) offered by the Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI). They are given knowledge about the problems encountered in food preparation, adulteration, labelling and every related aspect, says Bindu.

However, there is no system in place to ensure that every home chef or small manufacturer has such certification. There are two types of licenses offered by FSSAI: The first is a registration required for everyone who prepares any form of packaged food, while the second is the FSSAI licence meant for branded and unbranded big manufacturers. FSSAI inspects manufacturers who hold a licence, but inspections of those who have just registered are rare, as they are numerous and the scale is small, explains Bindu.

Thus, the lack of surveillance in the food and beverage industries, as well as a shortage of skilled and trained staff, are major issues. The government’s own systems lack trained staff. “The government is doing its best to train people, yet there is a shortage of food safety supervisors. Thirty-six lakh supervisors are required in the country, but over the past seven years, we have only received 15 lakh of them, which is approximately 40% of the total requirement,” Shashikanth adds.

Lax implementation

Thus, while FSSAI has robust safety rules, the problem lies in their implementation. A foolproof mechanism to implement the existing rules is the first requirement.

Another problem is in communication. Although the FSSAI has communication and awareness materials and rules, there is no mechanism in place to measure their effectiveness, nor is there any evaluation. The content is not localised enough in all languages to reach those who do not know English or those who cannot read at all, so the information can be non-inclusive.

Thirdly, as Shashikanth puts it, the implementation of food safety at the bottom of the pyramid among food manufacturers is the key. “Nearly 25- 40% of people depend on street food, but it is not regulated enough,” he adds. Street foods, small eateries, hotels, and establishments, as well as government-owned schemes like dasohas in temples and mid-day meal schemes, should all be supervised for food safety.

Even if the government can supervise, fresh farm produce and meat do not fall under the supervision of FSAAI. Therefore, people should buy from trusted sources, say experts. And when in doubt, go to the regulator.

A shared responsibility

“There is always a possibility of unsafe food being grown, with or without the farmer knowing it. If anyone has any doubts about a food item, complaints can be made to the local food inspectors. Anyone can submit the samples to them for testing, or the inspectors themselves can conduct the testing. Most people are not aware of this,” says Narayan.

So, with the government being short-staffed and the public not being knowledgeable or equipped enough to identify contamination and safety issues, whose responsibility is it to ensure food is safe?

Bhaskar Narayan offers a perspective: “Safe food is a shared responsibility. It begins with our daily habits. We have the responsibility to walk gently on this earth, not burden her with polluting deeds, and protect the environment, air, land and water for all. And that’s just one part of keeping food safe.”

What you can do in case of contamination

l Collect evidence

l Keep the food sample in its original packaging.

l Note the purchase receipt, including date, place, batch number, and expiry date.

l File a complaint online through FSSAI’s Food Safety Connect App or the Food Safety Complaints Portal: https://foodlicensing.fssai. gov.in/cmsweb/

l Alternatively, you can call the FSSAI Helpline: 1800-112-100, email at complaint@fssai.gov.in or write to the local Food Safety Officer (FSO) of your district.

l Submit the sample if asked.

l Do not get the sample tested in private labs unless advised or accepted by the FSSAI. Only NABL-accredited or FSSAI-approved private labs test the sample.

l If the food is contaminated, the manufacturer is penalised and fines could be up to Rs 10 lakh. Product recall, license cancellation, and imprisonment are also possible in severe instances.

l False complaint: Penalty if the intent of the complainant is proven to be malicious.

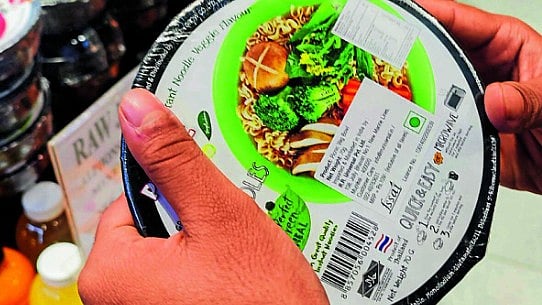

How to read food labels

The labels on branded packaged items are to help you understand whether a food product is safe, nutritious, and compliant with regulations.

FSSAI logo and license number: Ensure that the logo is original by comparing it to the one on the website. The 14-digit FSSAI license number appears beneath the logo. Verify this number on the FSSAI website for authenticity. You can find out what the licensing is for.

Food category and ingredients: Additives like preservatives or flavour enhancers will have INS numbers (e.g., INS 211 = sodium benzoate).

If you have allergies or dietary restrictions, check this part carefully.

Other elements to look out for:

a. Nutritional information

b. Symbols for vegetarian/non-vegetarian food

c. Manufacturing and expiry dates

d. Net quantity and price

e. Manufacturer information and consumer care