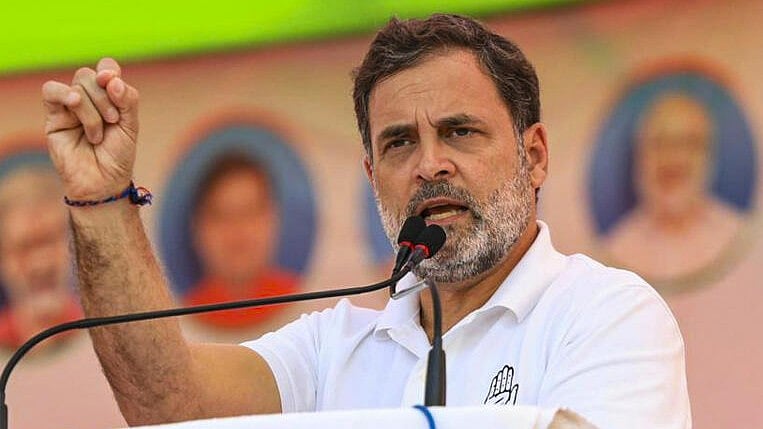

LoP in the Lok Sabha and Congress leader Rahul Gandhi addresses a public rally.

Credit: X/@INCIndia via PTI Photo

By Andy Mukherjee

What’s a Latin American hairdresser doing in a local election 9,000 miles away?

At a press conference in New Delhi last week, Rahul Gandhi, the leader of India’s opposition, posed just that question, as he filled the screen behind him with excerpts of electoral rolls from a state poll last year. Each of the 22 women on the list had a different name, like Seema, Sweety and Saraswati. But they all carried the same stock picture of a young woman. Gandhi identified her as a Brazilian fashion model.

Larissa Nery, a 29-year-old from Belo Horizonte, Brazil, later confirmed that the photo was indeed hers, though she is a hairdresser, not a fashion model. She has, nonetheless, become an overnight sensation in India, the face of what Gandhi claims is an organized scheme to subvert the world’s largest democracy.

According to data compiled by his investigations team, the voter identities created with Nery’s photo were part of 2.5 million such fake records in the 2024 assembly polls in Haryana. One in eight voters in the northern state were fake, he said. “They either don’t exist, or they’re duplicate, or they’re designed in a way for anybody to vote,” he said. (Gandhi’s Congress party effectively lost its chance to wrest power in the state by under 23,000 votes to Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party.)

This was Gandhi’s third attack in four months on India’s Election Commission, which he has accused of running a systematic campaign of “vote chori” — “vote theft” in Hindi — in collusion with the BJP. After his first presentation in August, the three-member body held its own press conference in which it dared the opposition leader to file an affidavit within seven days to make his claims official — or apologize to the nation.

Gandhi did neither. This time, the commission has asked him to explain why no objections were filed when electoral rolls for Haryana were shared ahead of the polls with all political parties. A BJP minister said the attack on the integrity of elections was part of a well-planned conspiracy to damage the country’s image.

In his Ted Talk-style presentation, Gandhi directly addressed Gen-Z voters, warning them that India’s democracy was in peril. In recent years, even independent researchers have come to share that dim view. The V-Dem Institute, an independent research unit at the University of Gothenburg in Sweden, demoted the country to “electoral autocracy” in 2021. India’s trajectory “is emblematic of the world’s democratic recession,” Oxford University political scientist Maya Tudor noted in her chapter for a 2024 book.

In a 2023 paper, economist Sabyasachi Das described what according to him was statistical evidence of manipulation. It “appears to take the form of targeted electoral discrimination against India’s largest minority group — Muslims,” he wrote. Amid the furor triggered by his research, Das resigned from India’s Ashoka University the same year.

Shrugging off domestic politics

Credit: Bloomberg Photo

Over the past decade, global investors have cared little about any of this. After a short spike in market volatility following the unexpected erosion of the BJP’s majority in last year’s parliamentary election, the bigger shock for investors has been the sudden deterioration in New Delhi’s international standing. Nobody expected President Donald Trump to banish his friend to a tariff hell, while doing a trade deal with China.

That debilitating 50 per cent tax on exports to the US, and the fact that a frothy stock market has nothing to offer in a high-growth area like artificial intelligence, is what’s making them sour on India, not local politics. With domestic retail investors fueling a $200 million-an-hour boom in initial public offerings, Gandhi’s vote theft allegations are a sideshow even to the middle class. The unemployed youth care more about finding jobs. The apathy is partly because opposition parties have no obvious end goal. No matter how unfair they allege the elections to be, it’s highly unlikely that they will ever boycott them.

Take Bihar, where polling in two stages began a day after Gandhi’s Nov. 5 press conference. (Results will be announced Friday.) The eastern state is currently under the BJP’s indirect control. Nitish Kumar, the 74-year-old chief minister, is a key Modi ally. To present a credible alternative to BJP’s Hindu right-wing politics, Gandhi, and his coalition partner, regional politician Tejashwi Yadav, badly need a win in the poorest Indian state.

But the Election Commission’s role has come up for scrutiny in Bihar, too. The watchdog is facing legal challenges in the Supreme Court to a last-minute overhaul of the state’s electoral rolls. The recast has disqualified millions of existing voters.

Since the commission wants to take the so-called “special intensive revision” national, Tamil Nadu has preemptively challenged the constitutional validity of such an exercise. The southern state will go to the polls next year. Just as making a dent in the poor, overpopulated north is important for Gandhi, expanding the BJP’s reach in the rapidly industrializing and relatively more affluent south is crucial for Modi.

India’s elections were never perfect. But while it was hoped that a fully electronic process would end decades of violent hijacking of polling booths, especially in rural and remote areas, automation hasn’t done much for robustness.

Analysts have expressed alarm over poll percentages that keep rising even after voting has ended. The Election Commission, which says late-arriving data takes time to collate, has refused to make available CCTV footage from booths on privacy grounds. Opposition politicians say the opacity allows people to cast ballots from multiple locations, or under manufactured identities. The commission has repeatedly rejected such claims as false and misleading.

If nothing else, Larissa Nery’s unwitting entry into the battlefield will add to calls for greater transparency. Although his presentation fell short of proving that the Brazilian hairdresser’s picture was indeed used to steal 22 votes from Congress, Gandhi has nonetheless raised a significant doubt about the health of India’s electoral democracy.

Disclaimer: The views expressed above are the author's own. They do not necessarily reflect the views of DH.