Credit: DH ILLUSTRATION

In slaughterhouses, a deep horizontal cut into the neck of a chicken severs the vital carotid arteries and external jugular veins. Since these arteries carry oxygenated blood to the brain, dissection of the same is fatal. Metaphorically, the ‘Chicken’s Neck’, like its anatomical reference of acute vulnerability, is also used to describe a pregnable part of physical land that could be threatened by an enemy nation to cut the territorial integrity of a nation. Typically, such a cartographical passage is essentially narrow and connects larger landmasses on either side, but that narrow passage or corridor bestows acute vulnerability or susceptibility to a dangerous attack by an enemy nation.

When demographics are conflated with the lay of the land of India, the “crown” of Jammu & Kashmir (including Ladakh) at the very top offers a neck-like protrusion. Unsurprisingly, the self-appointed Field Marshal of Pakistan, Asim Munir, had infamously stated, “Kashmir is our jugular vein; it will remain our jugular vein; we will not forget it”. While Munir’s referencing of the jugular vein was beyond cartographical context, there is a narrow islet that the Pakistanis call ‘Akhnoor Dagger’ and is better known this side of the Line of Control as ‘Chicken’s Neck’. A strategic Pakistani land protrusion into India between the Chenab River and its tributaries affords a dangerous proximity to the vital bridge across the Chenab to Akhnoor. Its natural launch-pad location ensured that it was the focal point of Pakistani efforts in the 1965 Indo-Pak war to capture Akhnoor (Operation Grand Slam) and potentially choke Indian supplies to the Kashmir Valley. Pakistanis had expectedly launched a ferocious attack through the corridor and overran the intervening Chamb village and but for a heroic defence followed by a surreal counterattack by the Indian Army, Akhnoor came close to a fall.

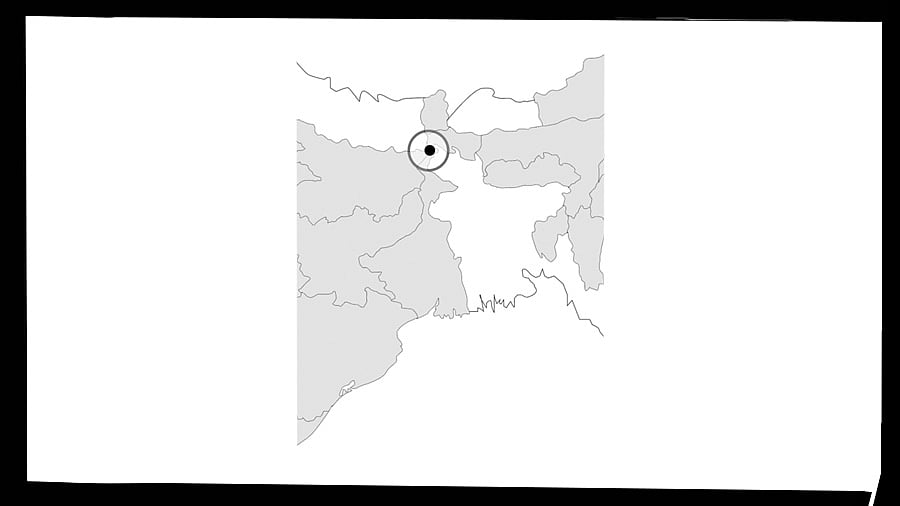

But there is another ‘Chicken’s Neck’ that has haunted the Indian security thinking –the Siliguri Corridor, a narrow stretch (20-22 km at its narrowest) that connects the North East states to the larger Indian land mass. This sensitive patch has Bangladesh to the southwest, Nepal to the northwest, and Bhutan to the north. But more importantly, ahead of Bhutan is the Chumbi Valley Tibetan region of China. This is where the infamous Doklam plateau (which saw a Chinese buildup in 2017) slopes into this narrow corridor. This is where the Chinese threat of attack is perennial. A possible intrusion of less than 130 km by the Chinese forces could potentially sever the North East states from the rest of India – a scenario that was somehow avoided in the 1962 Indo-China War. Understandably, this narrow corridor is heavily militarised (by India’s Trishakti Corps), with the Indian Air Force’s foremost Rafale fighter air base in the Hasimara Air Force Base.

However, over time, Indian defence planners have not only beefed up the security apparatus but also ensured additional, parallel, and even complementary infrastructure that has redressed the security preparedness considerably. Beyond this build-up, other options including tunnelling, agreement with Bangladesh to permit transit through its landmass, strengthening connectivity at the trijunction last-mile of Doklam in Bhutan, and multi-modal transport options within the corridor are on the planning table. This has counter-intuitively ensured that this ‘Chicken’s Neck’ is arguably India’s strongest line of militaristic defence.

In a troublesome development with the evolved political reality of Bangladesh, a slew of Pakistani and Chinese military personnel were taken to Bangladesh’s northern theatre manned by its Rangpur Division (near the Siliguri ‘Chicken’s Neck’). Reports of China helping Bangladesh rebuild the WW2-era airbase at Lalmonirhat, barely 20 km from the Indian border, have further raised hackles.

The Malacca Dilemma

But the practical curse of a ‘Chicken’s Neck’-like choke-point is not exclusive to India, as the Chinese too have their own corridor of extreme vulnerability. The ultra-narrow Malacca Strait (1.5 nautical miles wide at its narrowest) connecting the restive South China Sea and the Andaman Sea, between the Malaysian Peninsula and Indonesia’s Sumatra Island, is overlooked by India’s Andaman and Nicobar Islands. Besides being the world’s busiest and most congested sea lane that accounts for approximately 30% of all global trade, it is critically funnelling well over 75% of China’s energy requirements that sustain the Chinese economic juggernaut. A potential wringing of this ‘Chicken’s Neck’, even temporarily, presents a capitulating situation for China. Today, China’s naval capabilities disallow an impactful presence at this distance from their existing bases, and it is only the navies of the Sino-wary ASEAN countries, or more worryingly for the Chinese, the Indian Tri-Services Command at the Andaman and Nicobar Islands that have the military muscle to flex in a potential scenario around the Malacca Straits. Therefore, gargantuan infrastructural initiatives such as the Belt and Road Initiative, the China Pakistan Economic Corridor pivoted at Gwadar Port, Pakistan, and the ambitious

Polar Silk Route, developing Arctic shipping routes, are afoot. The Chinese sense that their lifeline runs through the Malacca Strait, where India, rather than China, has decidedly more leverage.

It is hardly surprising that the Indian footprint and investments in and around the Andaman and Nicobar Islands have gone up substantially and that naturally affords a stronger grip over the Chinese ‘Chicken’s Neck’ at the Malacca Straits, in any eventuality. However, like India is taking measures to mitigate and re-route its dependence around its own ‘Chicken’s Necks’ in J&K and Sikkim, the Chinese too are doubling up efforts to allay their fears of the ‘Malacca Dilemma’. The ‘Chicken’s Neck’ phenomenon has proved critical in previous conflicts, but nations including India are now better prepared from their past experiences.

(The writer is a former Lt Governor of Andaman and Nicobar Islands and Puducherry)