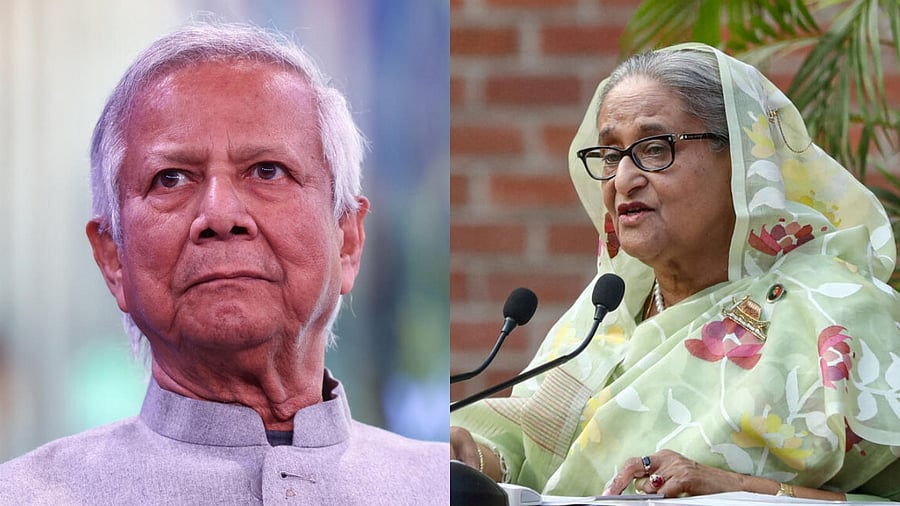

Interim Bagladesh Government head Prof Muhammad Yunus (left) and Former Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina (right)

Credit: Reuters

By Mihir Sharma

When Sheikh Hasina, Bangladesh’s ousted prime minister, was condemned to death last week, many in the country saw the sentence as appropriate for a leader who unleashed security men with rifles on helpless protestors. Others, more quietly, will have seen it as a straightforward act of judicial vengeance.

It is also a signifier of the missed opportunities and misplaced priorities of those who replaced Hasina in power. They chose retribution instead of reconciliation, and now they’re losing their chance at peace and stability.

The leaders of the new establishment — including 85-year-old Mohammad Yunus, who won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2006 — should realize by now the danger of their single-minded focus on eradicating from public life Hasina’s Awami League and the secular nationalism it defended. The interim government should instead work to restore the institutions that Hasina’s long tenure in power had eroded: the security services, the bureaucracy, and the judiciary.

Time is running out. Elections are due in February — and whoever wins will have a mandate tainted by violence and weakened by the enforced absence of the League.

Worse, aspects of the new Bangladesh look suspiciously like the old one, just with different targets. A group of six global human rights organizations wrote to Yunus last month warning him that “the security sector remains largely unreformed and that members of the security forces have not been fully cooperative with accountability and reform efforts.”

Local rights bodies agree. Their reports reveal that extra-judicial disappearances have intensified, and they blame the same security forces that Hasina relied on to maintain her regime. More bodies have been recovered from the delta country’s numerous rivers this year than last.

The reality of continued violence doesn’t square with Yunus’ optimistic tone and the high-minded rhetoric of the student leaders who began the protests against Hasina last year. But it’s a warning sign ahead of election season.

The Awami League, however discredited Hasina’s own leadership might have been by the end, does occupy an important position in Bangladesh’s journey to nationhood. If Yunus steps aside as radicals try to erase the roots of Bangladeshi nationalism, he won’t restore democracy. He will instead create a vacuum, one that will be filled by fundamentalists and criminals.

Islamists are already on the ascendant. This is a sadly familiar dynamic: In many countries emerging from a spell of autocracy, the quickest to re-organize are the religious fundamentalists. Think of Egypt after Hosni Mubarak fell.

And they are determined to lock in their temporary advantage. A senior leader in the Jamaat-e-Islami, the main Islamist political force, attracted criticism last week when he demanded that “all members of the administration” be brought under his party’s influence before the elections.

The Bangladeshi Islamists have influential allies and predictable enemies. On Nov. 15, a rally in the capital Dhaka demanded a crackdown on the Ahmadi sect. Campaigns against this minority elsewhere in the Muslim world have been a useful recruiting tool for extremists. Some of those who benefited from anti-Ahmadi drives addressed the rally, including Fazl-ur Rehman, the leader of the Pakistani wing of the Jamaat.

Other religious minorities are also threatened. Attacks on Hindus have become commonplace. But Christians are also freshly insecure, after bombs exploded near Dhaka’s Roman Catholic cathedral and a parochial school nearby. Even groups that have long been treasured as keepers of Bengal’s syncretic culture, like the mystics and folk singers known as Bauls, are being arrested and persecuted.

Criminals have also benefited from a governance vacuum. After Hasina was driven out, dozens of gang lords were allowed to leave jail, and are now clashing in an effort to reclaim their former territories. Inevitably, some of them are being recruited by political parties desperate for on-ground muscle.

Put this picture together, and you can see, in frightful clarity, a state retreating — retreating from the creation of a national sensibility and inclusive vision, and from its core function, monopoly over the use of force.

Some within the new establishment are disturbed. The interim government’s Information Adviser, Mahfuj Alam, warned this weekend that “the oppressed are becoming oppressors… Those who replace injustice with new forms of oppression and violence will be responsible for the revival of fascism.”

The rest of the government should listen. Their primary responsibility is to restore Bangladesh’s institutions and to return its economy to high growth. The two are connected: They just need to look to their former rulers in Pakistan if they need an object lesson in how lawlessness and extremism are guaranteed to cause economic stagnation.

True justice for Hasina’s victims would lie in creating a judiciary that is seen to be independent, security forces that are accountable, and a polity with a place for all parties. Bangladesh needs a fresh start, not old executioners with new mandates.

(Disclaimer: The views expressed above are the author's own. They do not necessarily reflect the views of DH.)