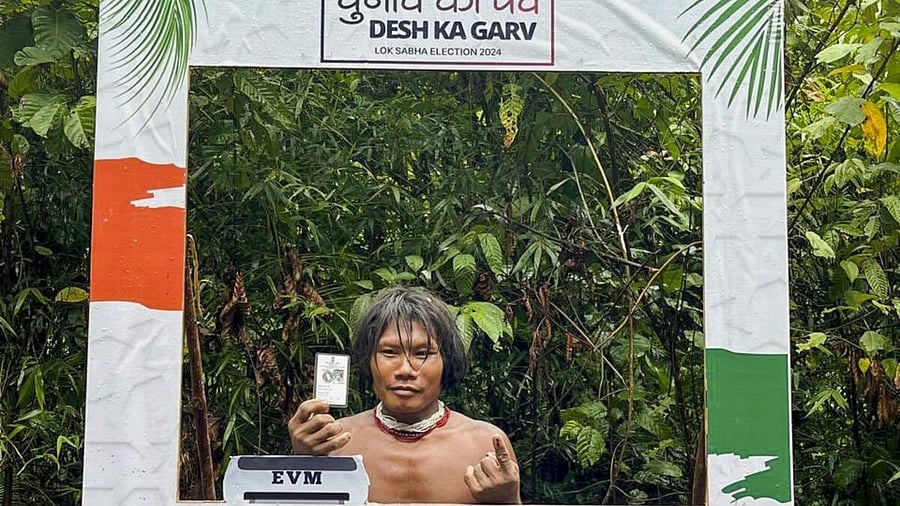

A voter from the Shompen tribal community poses for a photo after casting his vote.

Credit: PTI Photo

In a recent development, Prof Vishvajit Pandya, director of the Andaman and Nicobar Tribal Research Institute (ANTRI), underscored the findings of his report on the Shompens, one of the primary aboriginal communities inhabiting the interior forests and coastal areas of the Great Nicobar Islands (GNI).

In an interview with a media outlet, he highlighted that the Shompens oppose government projects encroaching on their uphill forests, which are primarily around the Galathea River basin, where most of their camps are concentrated. The report, published in 2020, underscores this sentiment, yet no response has been received from the Union administration so far.

The proposed Great Nicobar Project, planned for this region, involved constructing an international container transshipment terminal, a greenfield international airport, gas- and solar-based power plants, and township and area development projects. The project requires 166.10 sq km of land, including approximately 130.75 sq km of forest area, as detailed in the environmental clearance documents.

The Shompens are nomadic tribes living in the interior of this island beyond the beach forest zone, categorised as their microenvironments, which is their small-scale localised ecosystem critical for their livelihood. Currently, they are classified among the Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Groups (PVTGs) in India.

According to the 2011 Census, their population stood at 229 (141 males and 88 females). They rely heavily on the tropical evergreen forests of GNI for their food, especially pandanus (screw pines), their staple diet, which is supplemented by animal-based foods such as sea fish, lobsters, prawns, mussels, and wild boar.

The study published in the Journal of Anthropological Survey of India (2017) revealed significant heterogeneity among different groups and sub-groups of the Shompens, who do not all live together. While the tribe has adapted to cultivating bananas, tapioca, yams, coconuts, colocasia, and green chillies, besides screw pines, their primary concern is the loss of forest land, which grows their tapioca gardens. The project threatens their matrilineal land practices, which are integral to their marriage, kinship, land, and water management systems.

The Shompens are highly vulnerable to diseases and prone to being a degenerating race. A 1990 study, following the 1981 census, noted their population plummeted from 214 to 134 due to an epidemic outbreak of gastroenteritis.

The Shompens do not allow outsiders to enter their main camps in the forests and resist any contact with their children and women or provide outside foods to avoid transmission of infections and diseases from the outsiders, as per the findings of research in the Journal of Anthropological Survey of India (2020). The Great Nicobar Project risks exacerbating such fears and health vulnerabilities.

Additionally, outsider influence has altered their traditional clothing patterns, increasing their susceptibility to respiratory ailments as noted in the 2020 study.

The rationality of doling out rations to the community had increased post the 2004 Tsunami Disaster. The need for this ‘goodwill gesture’ has even been enquired of in the study ‘The Southern Nicobar Islands as Imaginative Geographies’ (2016). Rather, the consumption of non-traditional food such as dal (lentil), rice, cooking oil, and biscuits poses health risks to the indigenous community.

The fear of history repeating itself is not unfounded. The Tribal Reserve Territory created in 1956 to prevent exploitation of the Jarawas and their forests was rendered futile when the Andaman Trunk Road bisected their forest in 1978, leading to disease outbreaks and exploitation.

Claims of ‘empty spaces’ for the Great Holistic Project are also in conflict with the 2015 Shompen Policy, which clearly puts the welfare of the tribe right at the top. Without a clear plan of action to safeguard the Shompens, these claims might prove to be a sham.

Way forward

Minimal intervention in healthcare: While the routine medical facilities must be introduced in a phased manner, intervention must remain minimal. The Indian Journal of Medical Research Survey (2024) reported good progress in detecting anaemia prevalence, fungal infection of the skin, acute respiratory infection, and abdominal pain among the Shompens. Further, developments on better equipping the sub-medical centre in the New Chingam village, Campbell Bay tehsil, should be ensured, since visiting the two primary healthcare centres in non-tribal areas of Campbell Bay might not always be conventionally possible for the tribes.

Culturally sensitive education: Schools and welfare programmes initiated by ANTRI should be in consonance with the Shompen’s cultural norms. Anti-schooling feelings must be prevented through patient and inclusive implementation.

Forest preservation: Uphill forests, vital to the Shompens’ survival, should remain untouched. Their preferences, as outlined in the 2020 video report, must guide conservation efforts.

Emic-based approaches: Research methodologies must focus on the description and understanding of the culture as perceived by the community members to understand their needs and promote measures for their survival. For instance, a 2020 ethnobotanical study conducted among the Shompens revealed interesting information about 43 plants and artefacts used in shelter, transportation, hunting, fishing, food gathering, ornamentation, cooking vessels, fire drills, and dressing purposes.

Respect for autonomy: Viewing the Shompens as merely “shy” is reductive. Respecting their autonomy and cultural practices is crucial for their survival.

(The writer is a student at the National Law University, Delhi)